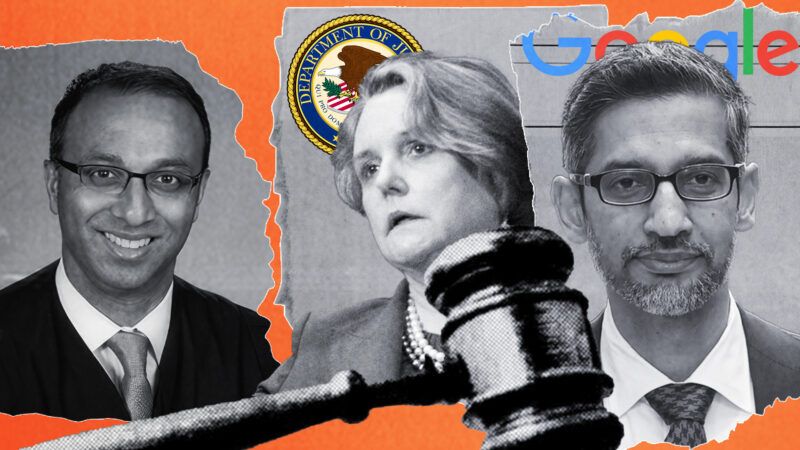

Trump and Biden Tried To Break Up Google. Now, They've Both Failed.

A federal judge rejected the proposed structural remedies in the Google search engine monopoly case.

The federal government's five-year-long antitrust case against Google has ended. Instead of forcing the tech giant to divest from Chrome, a federal judge on Tuesday opted "to allow market forces to do the work."

The suit was first brought against Google in October 2020 by President Donald Trump's Justice Department (DOJ) and 11 states, who complained that the company had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by monopolizing the general search services, search advertising, and general search text advertising markets in the United States. Judge Amit P. Mehta of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia—the same judge who issued Tuesday's decision—ruled in favor of then-President Joseph Biden's DOJ in August 2024.

In November 2024, the Justice Department proposed wide-reaching actions that the federal government said were necessary to address Google's monopolization of the search market: divestiture from Chrome; conditional divestiture from Android; termination of its paid partnerships with Apple and Android; forced sharing of its search, user, and advertisement data with competitors; and prohibition on "query-based AI product" investments. In March, the Justice Department submitted its revised proposal, which largely maintained these remedies but eliminated the AI-investment prohibition.

On Tuesday, Mehta rejected the proposed Chrome divestiture, saying it "cannot reasonably be described as a remedy 'tailored to fit the wrong'" and characterized the contingent Android divestiture as suffering "from similar legal infirmities." Mehta declined to forbid Google from paying distributors like Apple for default placement of its search engine on its iPhones in light of the "GenAI products that pose a threat to the primacy of traditional internet." Doing so would disadvantage "Google in this highly competitive space."

Geoffrey Manne, president of the International Center for Law and Economics, says that Mehta's refusal to enjoin Google from making payments for search access is "entirely borne out of adherence to a consumer-welfare-focused antitrust and rejection of the 'big is bad' vision underlying the [Justice Department's] proposed remedies." Likewise, Mehta's rejection of the choice screen remedy, which would've required users to choose their device's default search engine on first use and again every year thereafter, "recognized that judicial micromanagement of product design would not be beneficial for innovation or consumer welfare in the long run," says Manne.

Mehta did prohibit Google from maintaining exclusive distribution agreements that condition access to the "Play Store or any other Google application on the distribution, preloading, or placement of Google Search." He also sided with the plaintiffs on some search-index data-sharing provisions but opted for a narrow definition of search index, which excludes user-side data and only includes information about websites. Qualified competitors will only receive a one-time snapshot of this search index data, not the ongoing, periodic disclosure proposed by plaintiffs.

Mehta rejected the plaintiffs' advertisement data remedy "given [its] poor fit and dubious efficacy." However, Mehta ruled that Google must disclose its "user-interaction data that associates queries and results with user interactions" at least twice, as well as its "click-and-query data," as both are integral to Google's scale advantage. Still, he rejected the sharing of data used to train Google's generative AI app, Gemini, because "the GenAI product space is highly competitive [and Google] does not have a distinct advantage over chatbots."

In his decision, Mehta rightly recognized that Google's domination of the search engine market was not solely due to unlawful, anticompetitive behavior but in large part to its "best-in-class search quality, consistent innovations, investment in human capital, strategic foresight, and brand recognition." Mehta's refusal to break up Google has been called "a green light for monopolization to every big business" by some antitrust crusaders. Manne has another take; he says Mehta's decision is "definitely a win for consumer welfare over the vision of antitrust espoused by the [Justice Department's] proposed remedies."

Show Comments (12)