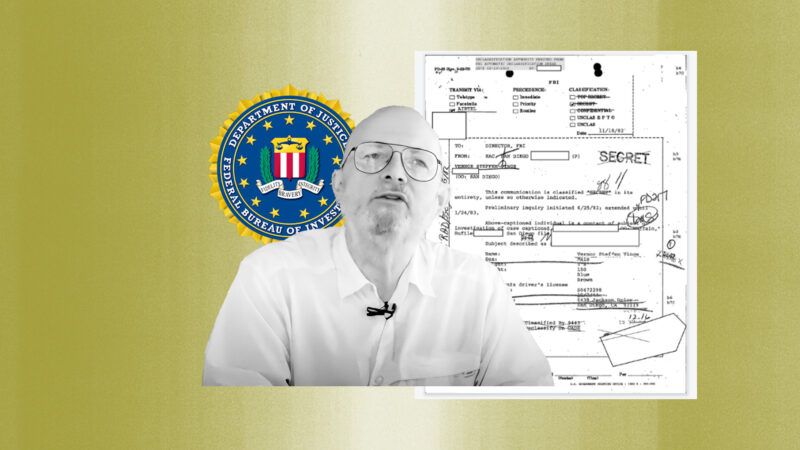

FBI Spied on Libertarian Sci-Fi Author Vernor Vinge In 'Espionage' Case

The late friend of Reason, who coined the term "technological singularity," landed on the feds' radar for his association with a foreign policy dissident.

Vernor Vinge had an active imagination. The computer scientist turned science fiction writer, who passed away in March 2024, won the Hugo Award several times for his groundbreaking novels on artificial intelligence and virtual reality. His 1993 essay, "The Coming Technological Singularity," has become a guiding idea of the modern tech industry. And he was interviewed twice by Reason, once in print and once on video.

The FBI, however, knew Vinge as a potential threat. His file, which was declassified in February 2025 and released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) last week, includes papers from a 1982 investigation into Vinge. While the full context of the case is redacted, one of the memos notes that Vinge "may have been in contact with Karl Amatneek," a fellow computer engineer who "is the subject of a current espionage investigation."

The FBI files gave another reason why Vinge was someone to watch: "Subject has a security clearance and works at a sensitive facility." That clearance, which was active from July to August 1981, came from Vinge's work with Tetra Tech, a government contractor in Pasadena, California.

Amatneek came under FBI scrutiny in the 1980s for his involvement in TecNICA, an organization that sent delegations of technologically-skilled volunteers to aid Nicaragua during the socialist Sandinista revolution. The FBI made its interest in Amatneek very clear to the people it interrogated, according to fellow TecNICA volunteers who spoke to the Los Angeles Times in 1987. They accused the Reagan administration, which was trying to overthrow the Sandinista government, of running a harassment campaign against foreign policy critics.

Fellow computer programmer and TecNICA member Louis Proyect gave more context to that investigation in a 2021 interview with Jacobin, published shortly after he died. When TecNICA leaders went to the Cuban embassy to inquire about expanding their volunteer projects into Cuba, they were sent to meet with a Cuban intelligence officer.

After the FBI found out, "they started going to places like Bell Labs, really top-of-the-line companies. They would go into the personnel office and say, 'Are you aware your employees may be working with an espionage network?'" Proyect said. He claimed that the FBI overplayed its hand, accusing the volunteers of giving away sensitive technologies to Cuba and the Soviet Union. "The media coverage was such a repudiation of the FBI that they ultimately just dropped their case against us," Proyect added.

It's unclear from the files whether or why Vinge was really associated with Amatneek—a teletype message from January 1983 says the relationship "has not yet been established" to the FBI's satisfaction and asks for more time to investigate—but it should have been obvious from the get-go that Vinge was not a supporter of socialist revolution.

His 1981 cyberpunk novel, True Names, follows a group of guerrilla hackers fighting against an overbearing, bureaucratic U.S. government. They discover that a recent revolution in Venezuela was actually orchestrated by a rogue National Security Agency artificial intelligence program "designed to live within large systems and gradually grow in power." If that wasn't on-the-nose enough, Vinge said in a 1987 interview with Prometheus that The Peace War, his 1984 novel* about a rebellion against a dystopian world government, was meant to make the case for "anarcho-capitalism."

Vinge later told Reason that "the millions of people who need to be happy and creative to make the economy go…are more diverse and distributed and resourceful and even coordinated than any government. That's a power we already have in free markets."

Then again, why would an FBI agent care? To him or her, the investigation was a matter of tracing out networks of associations that could be a threat to the government. Vinge seemed like he was hanging out with subversives, and he himself had some subversive ideas. It didn't really matter what the content of those ideas was. Ironically, Verner had mocked the incompetence of the surveillance state in True Names.

"The older cop continued the technician's almost diffident approach. 'In any case, Mr. Pollack, I think you realize that if the Federal government wants to concentrate all its resources on the apprehension of a single vandal, we can do it. The vandals' power comes from their numbers rather than their power as individuals,'" Verner wrote. "Pollack repressed a smile. That was a common belief—or faith—within government. He had snooped on enough secret memos to realize that the Feds really believed it, but it was very far from true."

* CORRECTION: This article originally misstated the publication year of The Peace War.

Show Comments (16)