Smartphone Study Authors Say Phones Should Be Regulated Like Alcohol and Tobacco

Parental responsibility? What parental responsibility?

A global study finds that owning a cellphone before age 13 is linked to "alarming mental health declines," according to SciTechDaily. The study—"involving more than 100,000 participants"—found that cellphone ownership before the teen years was linked to an increased likelihood of "suicidal thoughts, heightened aggression, feelings of detachment from reality, difficulties with emotional control, and diminished self-worth" at ages 18 to 24.

The authors of the study—which was published in the Journal of Human Development and Capabilities—are urging authorities to adopt policies "similar to those regulating access to alcohol and tobacco."

You are reading Sex & Tech, from Elizabeth Nolan Brown. Get more of Elizabeth's sex, tech, bodily autonomy, law, and online culture coverage.

Once again, we see an alarming decline in expectations of parental duty, paired with policy advice that just assumes a causation that the evidence doesn't show.

Putting Policymakers Above Parents

The paper recommends policies including "mandatory education on digital literacy and mental health," age-verification rules for social media and "meaningful penalties for non-compliance," banning social media platforms "on all internet-connected devices for children under 13," and implementing "graduated access restrictions for smartphones." It also says these policies should possibly be extended to apply to anyone under 18.

Noticeably absent from these proposed mandates? An emphasis on parental action.

It seems we've moved away completely from the idea that parents should shepherd kids away from risky or excessive use of technology. Why advise parents to avoid buying phones for their young children, or at least to limit their use, when we could just impose one-size-fits-all solutions on every family, costly legal burdens on tech companies, and massive privacy invasions on adults and minors alike?

Why respect parental autonomy on complicated decisions like these when we could just fine them like we sometimes do parents who let teenagers consume booze? The paper does not outright say we should do this, but it brings it up as an example of the kind of "multi-stakeholder approach" that the authors, led by Sapien Labs founder Tara Thiagarajan, would like to see.

It's absolutely wild to me that this is where the discourse on kids and screens has gone. We're completely abrogating parents of all responsibility, disallowing any sort of independent parental judgment, and suggesting that there is one and only one right solution for all families in all circumstances.

And we're doing it based on a totally biased reading of the evidence.

Biased Conclusions

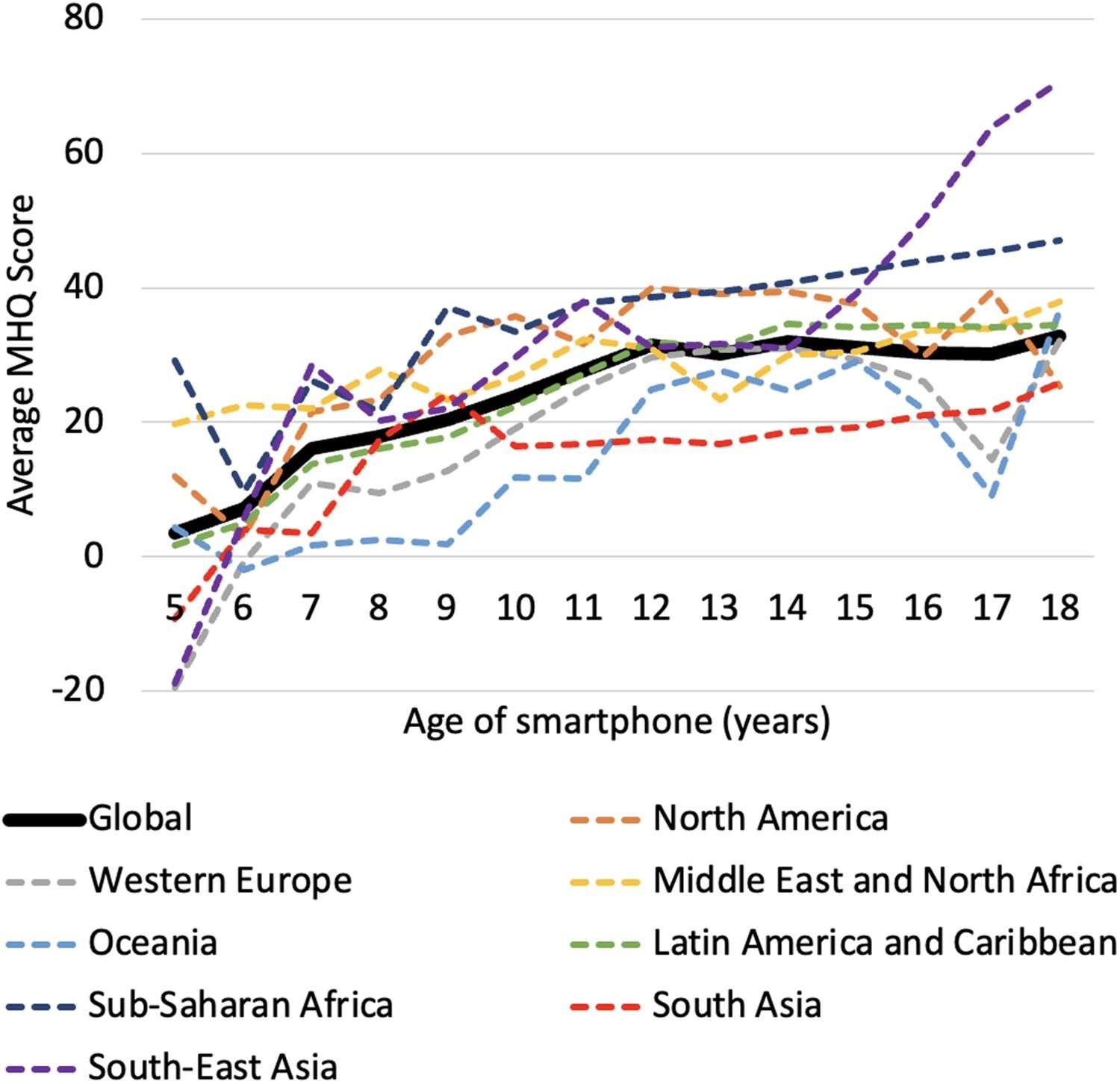

The alarmist view of studies like these says that kids using cellphones causes all sorts of mental health issues. After all, kids owning cellphones at age 12 or younger was linked to "poorer mind health outcomes," and for kids who got a smartphone below age 13, "overall mind health and wellbeing" was "progressively lower" with younger acquisition. Among young women especially, suicidal thoughts at ages 18–24 were significantly higher among those who got a smartphone at ages 5 or 6 compared to those who got a smartphone at age 13. Younger smartphone ownership was also associated with lower levels of emotional resilience in young women, while it was associated with diminished empathy, stability, and self-image among young men. To an alarmist, these links are all the proof we need for massive, society-wide policy interventions aimed at keeping kids off phones.

But this alarmist view rests on the assumption that cellphone ownership is the only difference between kids who first owned a cellphone at age 12, or 9, or 6 and those whose parents did not get them a cellphone until they were 13 or even older. Common sense tells us that this is almost certainly not the case.

The kinds of parents who get their kids a smartphone at age 9 are probably somewhat different than the kinds of parents who wait until their kid is 13. And the kinds of parents who give their kids a smartphone at age 5 are probably much different than the kinds of parents who wait until their child is 15.

These days, it is educated, middle- and upper-class parents who are less likely to get their kids a phone or tablet at an early age. So, some of the effects we're seeing linked with early phone ownership could be the effects of income and socioeconomic status rather than technology.

And regardless of income or class, the kinds of parents who permit screen time at an early age might be quite different in their parenting styles than those who do not. They might be more permissive, giving in to their kids' desire for a phone and to all manner of other things. They might be more absent and, thus, prone to use technology as a babysitter. They could be more Type A—the kinds of parents who overschedule their children and initially get them a phone to help coordinate between activities. Maybe they're more neurotic or controlling—the kinds of helicopter parents for whom giving their younger kids a phone to always be reachable is just one manifestation of greater hovering. Or maybe they're less neurotic, in a way that borders on negligence when it comes to tech and other areas.

We don't know, of course, but any—or all—of the above differences are at least plausible. And any, or all, of the above differences could help account for differing levels of aggression, detachment, and so on among the children exposed to these parenting styles across all domains.

There's also the possibility of some reverse causation in effect, too. Parents whose kids are already struggling with social, psychological, or behavioral issues may be more likely to get them phones at earlier ages. You can certainly see how someone with a particularly aggressive or hyperactive child who can be subdued by screen time might find it attractive or prudent to get them a phone a few years earlier than they might otherwise. Or how the parent of a socially withdrawn tween might be more likely to get their child a phone than would the parent of a kid happily occupied by many friends and outside pursuits.

Some of the effects seen here may indeed be a direct result of using particular online platforms, or of particular types of online engagement, or of the displacement of physical activities with digital ones. But with inevitable differences in the types of parents and children in these different categories, it would be foolish to attribute all of the differences to any smartphone use. And even if we could say for certain how much of the difference was directly related to phone exposure, that still wouldn't tell us what types of smartphone use are risky or cause damage, rendering any large-scale policy recommendations overly broad.

Details Matter

This is not to say that it's necessarily good to give your 2-year-old a tablet or your 8-year-old an iPhone, nor that it's a smart idea to allow your 11-year-old unfettered access to YouTube and TikTok. I think there are genuine reasons to be concerned about certain sorts of technology use among kids, especially at young ages.

But I also think that the devil is in the details here. Buying a toddler a tablet that can only be used to watch preapproved content on long road trips a few times a year is worlds apart from letting a 2- or 3-year-old have tablet time daily. Allowing a 10-year-old to have a cellphone with basic calling and texting features is different from giving them open access to the app store and the World Wide Web. Letting your teenager use a smartphone at specified times, perhaps with parental controls, is different than letting them take it to bed with them at night and stay up late scrolling whatever they want.

It doesn't help parents or children to condemn all screen time or all cellphone use in the same way, and it certainly doesn't help to have government nannies step in and make it the law of the land. The former is bad because it makes people feel guilty and paranoid about things that can make life easier and are extremely unlikely to have any negative effects. The latter is bad because it leads to invasive schemes that wind up with censorship and privacy invasions for everyone while also blocking teenagers and families from even beneficial uses of technology.

Studies like this one exacerbate these problems when they veer from neutral presentation of findings to positing causal relationships and advising on policy solutions.

Of course, there's nothing wrong with examining the way screen time, social media, or age of phone adoption is linked to well-being. But the data here—which comes from Sapien Labs' Global Mind Project—are being presented with a particular and expansive agenda in mind.

Before I wrap this up, I just want to point out a few more concerns about these data and the way they are being used:

• The traits being measured—and linked to cellphone ownership—come from "an online, self-report assessment tool." Depending on how the respondents were recruited (the paper does not say), this leaves open the possibility that longtime smartphone users with poorer mental health are more likely to want to opt in to a survey about smartphone use and mental health, and thus could be skewing the results.

• The study states that "for those who acquired their smartphone below the age of 13, their overall mind health and wellbeing is progressively lower with each younger age of first smartphone ownership." But while this might look like a straightforward trend when you consider all the geographical cohorts together, we also see some pretty wide and weird variance when we look at individual groups, especially when we include data on people who first obtained smartphones in their teen years.

In North America, for instance, owning a smartphone starting at age 5 is associated with better mental health in young adulthood than first owning a smartphone at age 6; first owning one at age 10 is associated with better mental health than first owning one at age 11; and first owning one at age 12 associated with equal or slightly better mental health than first owning one at ages 13 through 18.

In Western Europe and Oceania, first obtaining a smartphone at ages 16 or 17 is associated with lower mental health scores than first obtaining one in one's tweens or early teens. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the line bounces around quite a bit, with people who owned their first smartphone at age 5 scoring higher in mental health than those who first owned one at ages 6–8. In South Asia, there's not a lot of difference in mental health scores when a phone was first owned anytime after age 8—with the exception of first owning a phone at age 9, which was associated with higher mental health scores than first owning one at any other time until about age 18.

I'm not sure what to make of all that except to say that 1) cultural context seems to matter, and 2) while there exists a general trend of higher mental health being linked to older age of first phone ownership, it's far from being universal, linear, or consistently steep.

More Sex & Tech News

• Derek Thompson looks at some evidence for and against the idea that artificial intelligence is destroying jobs for young people.

• A federal judge "rejected a bid by Maine's largest reproductive health care provider to block U.S. President Donald Trump's administration from implementing a provision of his recently enacted tax and spending bill that would deprive abortion providers of Medicaid funding," reports Reuters.

• Texas and Florida have joined a lawsuit targeting the abortion drug mifepristone.

Show Comments (21)