Cincinnati's Beer-Loving Germans Endured Anti-Immigrant and Anti-Alcohol Resistance

The city's German immigrant experience suggests that immediate assimilation isn't necessary to eventual assimilation.

This is part of Reason's 2025 summer travel issue. Click here to read the rest of the issue.

Far below downtown Cincinnati, you'll find large stone- and brick-walled caverns with dirt-strewn floors. Their great arched passageways loom over piles of century-old rubble, vast vats that once overflowed with beer, and recently added stairways to assist tourists passing through.

As with so much in Cincinnati, we can chalk up these places to beer-loving German immigrants. The caverns were built for storing lager back before refrigeration was widespread. Unlike ales, lagers must be aged and stored at temperatures below 40 degrees. For the city's burgeoning German population to make the sorts of lagers they had known back home, they had to dig deep.

"The cities that made a lot of beer between 1850 and 1880, they all had lagering cellars," says Michael Morgan, author of Over-the-Rhine: When Beer Was King. In many places, these subterranean caverns would later be filled in. But not so here.

Curious Cincinnatians and tourists can now traverse recently rediscovered lagering cellars on tours organized by the Brewing Heritage Trail or American Legacy Tours. For a less rustic experience, they can visit Ghost Baby, a cocktail bar and music venue located in a renovated lagering cellar four stories underground.

A trip to—or below—Cincinnati's historic brewery district will take you to Over-the-Rhine, just outside Cincinnati's city center. When German immigrants started flocking to the city in the 1800s, many settled just north of the Miami-Erie Canal cutting through central Cincinnati. Locals began referring to the canal, derisively, as "the Rhine," and the German-heavy neighborhood just north of it as "over the Rhine." The nickname stuck.

Today this is often relayed as merely a charming little anecdote. But it hints at deep tensions between the city's earliest settlers and the huge wave of immigrants to come.

Cincinnati's population ballooned throughout the 19th century, from 2,540 residents in 1810 to 115,435 in 1850, when it ranked as the sixth-largest American city. By 1900, it had 325,902 residents, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Much of this growth came from immigration. In 1850, nearly half of Cincinnati's population was foreign-born. The bulk of Cincinnati's immigrants came from Ireland or Germany—especially Germany. By 1890, German immigrants or people whose parents were both German immigrants made up 57 percent of Cincinnati's population, according to "The 'Zinzinnati' in Cincinnati," a paper in the October 1964 Bulletin of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Cincinnati Germans tended to settle together, building German-language schools and churches, launching German-language newspapers, and starting social and philanthropic clubs for German Americans. Among the many businesses they launched were beer gardens and most of the area's biggest breweries. These included Christian Moerlein, founded in 1853 by a Bavarian immigrant, and the Hudepohl Brewing Company, founded in 1885 by the son of Bavarian immigrants. Both brands might still be familiar to beer drinkers today.

"There's no commodity manufactured anywhere in the history of Cincinnati that was as important to it as beer was," says Morgan. Cincinnati started brewing "long before it had these waves of German immigration," he points out. "But we really were defined by those German-style beers, and the way that they were made in Cincinnati."

German lagers were big in Milwaukee and St. Louis too, but not necessarily as good. St. Louis' biggest brewer, Anheuser-Busch, used rice to give its beers a lighter body, while the Milwaukee-based Pabst used corn. "In German brewing tradition, both of those things were really frowned upon," Morgan says. "They were a short cut—a way to make shitty beer." But Cincinnati brewers stuck to the German brewing tradition: nothing but barley malt, yeast, hops, and water. That's why, in parts of the 1800s, "Cincinnati was the most respected beer anywhere in the United States" and even exported to Europe.

Pork, soap, and some other industries may have technically been bigger, but beer was huge for Cincinnati's sense of identity, not to mention the local economy. In 1891–92, the locals spent "10 million dollars, or an average of $20 a person" on beer and ale, notes a 1938 Works Progress Administration book called They Built a City: 150 Years of Industrial Cincinnati. "Wages paid brewery workers at the time were among the highest in Cincinnati," it adds; "about four thousand men worked in the 33 Greater Cincinnati breweries that year."

Cincinnatians also made wine and spirits. "By 1850 three hundred vineyards covered nine hundred acres within 20 miles of the city" and employed about 500 people, according to They Built a City. Meanwhile, "local distillers were producing 1,145 barrels of whisky daily." (At one point, "practically every storekeeper in the city kept a barrel [of whiskey] on hand for customers, who got a free drink while shopping," the book claims. But "state and municipal licensing and regulations did away with free drinks.")

Alcohol created jobs in malt houses, ice houses, and the city's many, many saloons as well. "We were operating an astounding number of bars," says Morgan. By some estimates, there were nearly 2,000 bars in Hamilton County in 1919.

In German areas such as Over-the-Rhine, these bars and biergartens weren't merely places for men to drink. Many were family-friendly affairs, serving up food and live German music, hosting local clubs and societies, and generally serving as hubs for community.

Alcohol also helped Cincinnati expand from its central city core. Steep hills stretch up all around downtown and, before automobiles were widespread, it was hard to get hilltop settlements going. "The thing that eventually changed that was these short little railroads, the incline planes—we had five of them," says Morgan. The inclines were privately owned and made profitable by hilltop "resort houses," which featured ample entertainment and "astounding amounts of beer."

Today, visitors to these hilltop neighborhoods can still grab a piece of history with their pints by visiting the likes of Mt. Adams Bar & Grill (rumored to stem from a speakeasy operated by the infamous bootlegger George Remus) or Price Hill's Incline Public House, built on the site of the incline-era Price Hill House and featuring panoramic views of the river and downtown.

Over-the-Rhine now features a similar mix of hip and heritage, including Findlay Market, Ohio's oldest continuously operated public market, now surrounded by a spate of new restaurants, shops, and bars. (Try Maverick Chocolate; you'll thank me.)

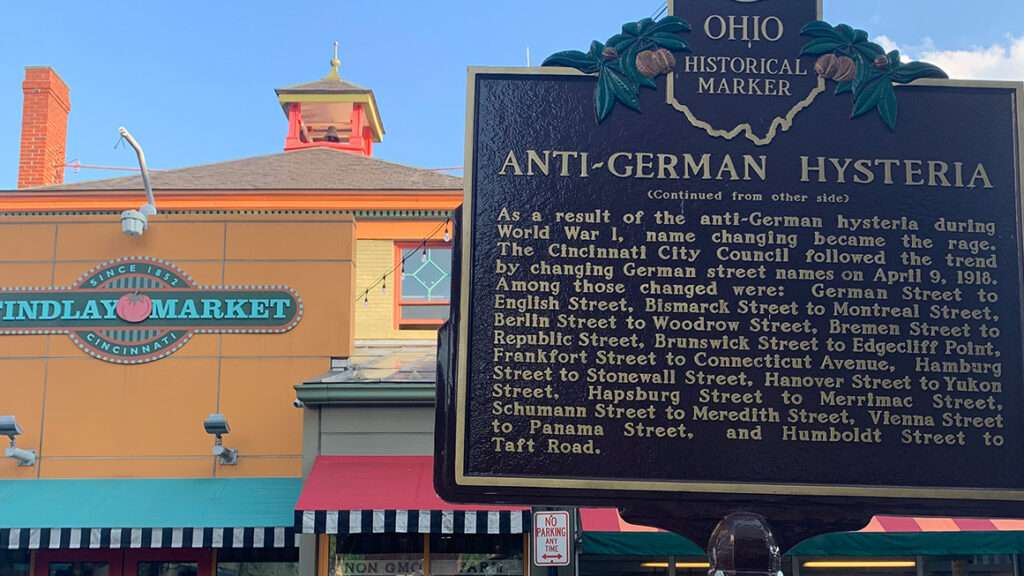

Some of the area's explicitly German character was wiped out during World War I. Today, however, you can still see the German immigrant influence in the city's celebrations, including a huge annual Oktoberfest celebration, and in some of its most distinctive foods, including Goetta—a part-sausage, part-bread breakfast dish descended from German grützwursts ("grain sausages").

There are surprisingly few distinctly German restaurants in the area. But across the river, in northern Kentucky (considered part of the greater Cincinnati area), you'll find Hofbräuhaus serving up classic Bavarian-American fare and Tuba Baking Co. offering creative twists on southwestern German food, including a Swabian take on Cincinnati's famous chili.

This dish, too, we can chalk up to immigration. You can find Cincinnati-style chili—cinnamon spiced, usually served over spaghetti and topped with a mound of cheddar cheese—all over the city, at chains such as Skyline and Gold Star or at independent chili parlors such as Camp Washington Chili (which nabbed a James Beard Award). The first of these was started by brothers who came here from Macedonia and aimed to create an Americanized version of a Macedonian lamb stew.

Cincinnati's ample saloons and breweries made it a focal point for the temperance movement, which often employed anti-immigrant sentiment in its appeals for a sober city. Several villages surrounding Cincinnati adopted anti-alcohol laws long before the 18th Amendment was passed.

The hilltop resort houses were eventually done in by blue laws. Few of Cincinnati's historic breweries bounced back after Prohibition. Of those that did, fewer still are around today.

Still, Cincinnati is rife with local breweries once again—around 40 in 2023, according to the Ohio Craft Brewers Association.

For craft, Morgan recommends Wooden Cask, West Side Brewing, and Urban Artifact (no one in the country is doing fruited sours better, he says). For ambience, he recommends Northern Row and the roof deck of Rhinegeist Brewery, both in Over-the-Rhine.

If you're traveling with kids, check out MadTree Parks & Rec, nestled into suburban Cincy's spectacular Summit Park. It features ample play space and my favorite local IPA, PsycHOPathy.

Cincinnati's latest influx of immigration has come from Africa, particularly Mauritania. German immigrants are old news now, and so is banning alcohol. But we're in an age of renewed unease about immigrants—especially those that speak their native tongues here or don't seem especially keen to "assimilate"—and renewed efforts to persuade Americans of the danger of drink.

In both regards, Cincinnati's German immigrant experience is instructive. It suggests that immediate assimilation isn't necessary to eventual assimilation, and that retaining pride in one's own language and customs isn't a barrier to building businesses and other institutions that enrich the wider community. It's also a reminder of the ways alcohol and establishments that serve it can bring people together and foster a sense of local identity and solidarity. In today's atomized, globalized, and oh-so-mediated times, that seems especially important—and, in its own way, healthy. Prost!

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "A City Built by Immigrants —and Beer."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

How many of them were members of violent criminals gangs in Germany? How many drive wagons through gatherings, set people on fire? How many raided apartment blocks? How many were supported by state-mandated taxation of others?

"And then, for no particular reason at all, the German people decided to elect Adolph Hitler."

You know who wasn't very welcome at our borders between the wars?

The obvious "Man soll den Tag nicht vor dem Abend loben" aspect of this take is laughable. Literally "The performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theater on April 14, 1865 was superlative save for the disruptive dispute going on in the audience that spilled onto the stage."

It's to the point of Reason: A

LibertarianLifestyle Magazine.Did they fly German flags at riots?

Read up on the Haymarket Massacre. Lots of revolutionary immigrants throwing bombs, including Germans.

>Cincinnati's latest influx of immigration has come from Africa, particularly Mauritania. German immigrants are old news now, and so is banning alcohol.

JFC, ENB - the Mauritanians are all Muslims. Banning alcohol will be right back on the table as soon as their numbers get large enough.

Also, this is another 'net benefit' article.

The authors assumes that any issues with the immigrants were the locals being xenophobic and that things are great now means they should have just put up with it so that some other people could enjoy the benefits while they bite the costs.

Reading about Cincinnati’s beer-loving German community and their resilience through anti-immigrant and anti-alcohol challenges really highlights how culture and tradition can persist even under pressure. It’s fascinating how these communities preserved their customs despite opposition, shaping the city’s identity over time. On a related note, running any hospitality or restaurant business today involves balancing tradition with efficiency. Tools like EATApp have been a real game-changer for me and many others in the industry. This platform streamlines reservations, guest management, and reduces no-shows, which ultimately helps restaurants run smoother and better understand their customers. The ability to track regulars and get real-time support is invaluable, especially in busy environments. For anyone managing a dining space, leveraging technology like Eat App can provide both operational ease and deeper insight into customer behavior—important for sustaining any business rooted in cultural heritage or modern demand.

Oh boy, spam is back.

I flagged it; they've got a new system, and last time I flagged such obvious spam, it actually got deleted, and the replies to it became top level comments.

This looks silly now. It was a response to a comment which was a reply to spam, which apparently has been deleted.

ETA: To be clearer: that comment looks like a reply to Incunabulum, now, and it was not, originally.

The current immigration problem is totally different. You see, Germans are white.

This dish, too, we can chalk up to immigration. You can find Cincinnati-style chili

I'm going to stop you right there. You do know that, unlike Deep Dish or New York-style pizza, which you can get in Seattle or Boise or Galveston or Tampa..., Cincinnati-style chili isn't even prevalent throughout The Ohio River Valley. Don't get me wrong, I like (Hoosier) Sugar Cream pie and wouldn't deny it to anyone, but I'm not such an idiot as to presume that people in CA or DC should know what it is and consider it to be an unbridled good.

You can buy Skyline Chili in cans as far away as St. Louis. However it isn't as good as eating it fresh in Cincinnati. Cincinnati-style chili isn't even German. It's a Mediterranean-spiced meat sauce. One of the biggest chili chains, Gold Star, was started by Jordanians.

Can Reason hire an actual editor?

Uhhh ... immediate and eventual are opposites. if someone does something immediately, they can't do it eventually. The only way something can be done eventually is to not do it immediately.

Or hell, maybe Kamala "Word Salad" Harris was hired at the Reason editor.

It is in response to the heartfelt Trumpian belief that immigrants who don’t immediately assimilate will never assimilate.

No, it's a question of grammar and dictionaries.

And you wonder why everyone accuses you of blaming Trump for everything.

And you wonder why you never get invited to parties.

By the way this “everyone” is just a half a dozen trolls who I keep on mute. Because, unlike you, I really don’t care what their personal attack of the day is.

You sure respond to a lot of attacks which you supposedly have muted.

immediate and eventual are opposites

So what you're saying is it's a really, really strong suggestion? 🙂

Maybe it's a lost in translation thing where Americans ask "How far?" something is and Germans answer in the time it takes to get there (punctually).

You can thank those fuckers for Tejano music too:

https://www.npr.org/2015/03/11/392141073/how-mexico-learned-to-polka

"Cincinnati's Beer-Loving Germans Endured Anti-Immigrant and Anti-Alcohol Resistance."

Note to Mr. Brown; All immigrants to the US faced anti-immigrant hatred, not just the Germans.

Cincinnati's chili is Greek meat sauce. It is not Swabian.

And the only issue Germans ever had here was when Germans, in Germany, were on the opposite side of a war.

"oh-so-mediated times?"

WHAT could THAT mean?

I fear Mauritanians MAY turn out to be different from Germans. VERY different, and not just in skin color.

I’m descended from the Cincinnati soup, all German Jewish and assimilation was immediate. I don’t count German beer consumption as displaying German heritage.