An El Paso Christian Charity Is Caught Up in Texas' Border Fight Against the Feds

Annunciation House feeds, shelters, and clothes immigrants. State officials say it's "systemic criminal conduct."

El Paso is the U.S.-Mexico border in miniature: Once a permeable landscape, the Texas city is now separated from its sister to the south—Ciudad Juárez—by a harsh apparatus of walls and wire. Thousands of people travel between the two cities daily, splitting their lives between two nations, all while debates rage over who may cross the border and how.

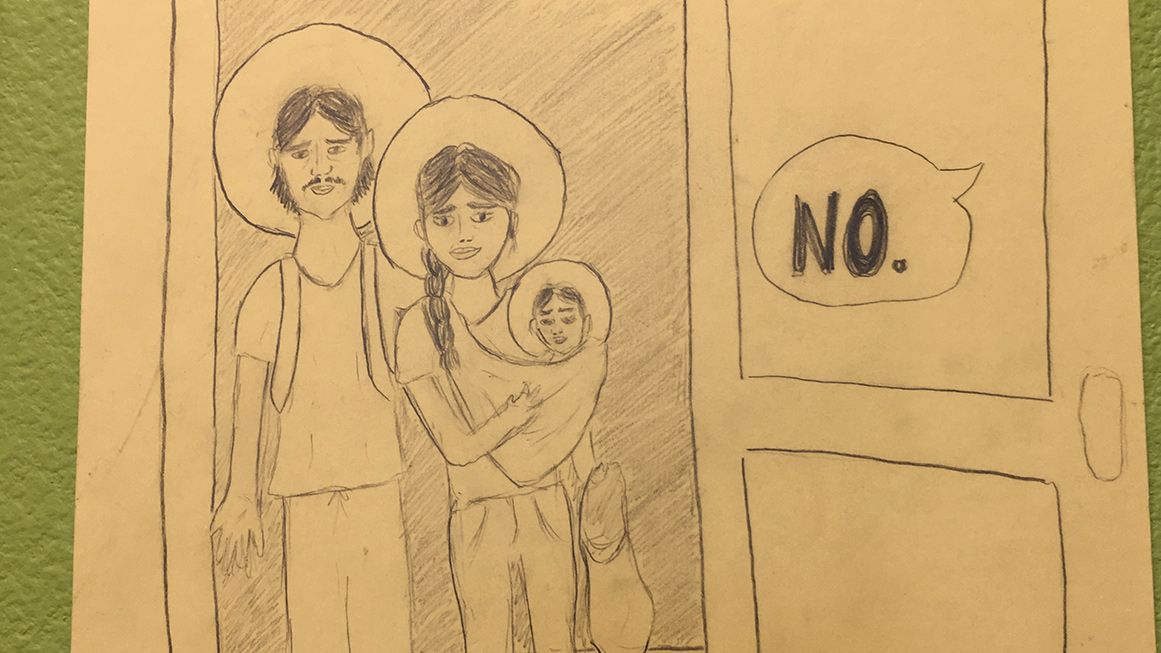

When five young Catholics set out to help El Paso's most vulnerable residents in the late 1970s, these questions weren't their primary concerns. "They were reading the Bible and saying, 'Where do we encounter God in this world? If we take our faith seriously, what kind of actions does that call us to?'" says Mary Fontana, a member of the board of directors (and longtime volunteer) at Annunciation House, a nonprofit that shelters and aids migrants.

"They kept returning to the idea that the God that they read about in the scriptures in the Bible was someone who identified first and foremost with the poor. And then they looked around their community of El Paso and said, 'Who are the poor in our midst?'" In El Paso, that "was primarily people who are undocumented," Fontana explains.

The Catholic Diocese of El Paso loaned the group a vacant floor in an old building, and in 1978 Annunciation House opened its doors. Its mission is "to provide hospitality and accompaniment for the poor in migration," says Fontana, offering "shelter, food, and clothing" to the city's "poorest of the poor." Annunciation House says it has helped "hundreds of thousands of refugees" since its founding.

This was meant to be a humanitarian mission—something many churches and religiously informed nonprofits view as an expression of faith rather than politics.

"We're just a bunch of regular folks trying to live out what we believe are principles of love and belief in the dignity of our fellow human beings, and there's really nothing secretive or sinister about it," Fontana adds. "We have a very mundane existence. We serve meals, we do a lot of laundry, and that's kind of it."

The state government takes a different position on the group's work.

Last February, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton's office launched an investigation into Annunciation House's activities and demanded the nonprofit turn over huge amounts of documentation about its immigrant clients more or less immediately. Then, in May, Paxton's office sought an injunction to stop what it saw as Annunciation House's "systemic criminal conduct."

The Office of the Attorney General (OAG) "has reviewed and obtained sworn testimony indicating that Annunciation House's operations are designed to facilitate illegal border crossings and to conceal illegally present aliens from law enforcement," a press release explained. "Annunciation House operates as a criminal enterprise."

In July, a state district court judge strongly rebuked that argument, calling Paxton's actions "outrageous and intolerable." Judge Francisco X. Dominguez ruled the state hadn't established probable grounds to shut down Annunciation House and had violated its religious freedoms. But that hasn't stopped Paxton, who hasn't just continued his pursuit of Annunciation House but is targeting other nonprofits that assist immigrants.

It is nothing new for faith-based groups to aid migrants; nor is it novel for the government to target them for that involvement. What's new about this case is its connection to recent debates over state vs. federal immigration authority. As Texas challenges the federal government on border policy, it has singled out Annunciation House as a complicit party.

'This Long Legacy'

Faith groups, many of them Christian, have long offered humanitarian assistance and protection to immigrants. In the 1980s, scores of Central Americans fled their war-torn countries and migrated to the U.S., but the U.S. government opposed granting them humanitarian status, instead deeming them economic migrants. Religious leaders began to consider housing the migrants in church buildings.

"Some of them start to argue, 'Well, we're not really engaging in civil disobedience, we're going to be engaging in civil initiative, because it's the government…that is failing to uphold its own law after having signed the 1980 Refugee Act,'" says Lloyd Barba, a historian of religion at Amherst College. "'So if the government is not going to uphold the law, we will take the civil initiative to uphold the law and offer protection for these migrants.'"

On March 24, 1982, several churches in California and one in southern Arizona announced that they would offer a safe haven to undocumented Central Americans seeking protection from deportation. "By the end of the decade, you have approximately 500 congregations that are formally part of the sanctuary movement," Barba explains. "An early estimate [says] that for every congregation that declares sanctuary, you've got 10 more that are providing resources."

As church groups were sheltering and aiding vulnerable migrants, the federal government was building a case against religious and lay volunteers. Undercover agents "attended worship services, Bible study meetings, and internal church discussions" as part of Operation Sojourner, "posing as committed sanctuary workers," explained the Center for Constitutional Rights. Three years after the sanctuary movement was born, the Center says, "the U.S. government indicted 16 people, including three nuns, two priests, a minister, and lay volunteers, on 71 counts of conspiracy and transporting and harboring refugees."

Eight sanctuary movement activists were ultimately convicted of 18 charges between them, all avoiding jail time. Despite the verdict, they pledged to keep the movement alive. "I plan, for as long as possible, to be part of a congregation that has committed itself to providing sanctuary for refugees," said Rev. John Fife, a co-founder of the sanctuary movement, after being convicted of three felonies.

Churches and faith-based nonprofits have remained major players in the sanctuary space, both in the literal sense and the broader work of migrant aid and welcome. Sanctuary churches "remobilized as deportations picked up under George W. Bush and then [Barack] Obama," wrote Shikha Dalmia for Reason in 2018. "Since Trump assumed office, the number of congregations opting to provide sanctuary has doubled from 400 to 800, according to Church World Service." Churches and nonprofits have continued to ruffle federal feathers, especially during periods of intensified government crackdowns on undocumented immigrants and the border.

In 2017, four aid volunteers with No More Deaths, a ministry of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Tucson, Arizona, left food and water for migrants in the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. They were convicted in 2019 on misdemeanor charges of entering the refuge without a permit and abandoning property. A federal judge overturned their convictions in 2020 on the grounds that "their activities were exercises of their sincere religious beliefs." Another No More Deaths volunteer, Scott Warren, was charged with harboring migrants after he provided them with food, water, and shelter in the desert. He was acquitted in 2019, also on religious liberty grounds.

Fontana says Annunciation House's mission "has really not changed" over the years. Early on, the organization assisted undocumented immigrants who couldn't access social services in El Paso. Decades later, it's still helping people who have nowhere else to turn. "By 2018, there were months when there were 1,000 people a day—families, mostly, parents and kids—being released from immigration detention in El Paso on a daily basis, and Annunciation House, along with a lot of community partners…got together to provide hospitality for those families," Fontana says. "The vast majority" of Annunciation House's guests now come from "[U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement] detention or from Border Patrol, Customs and Border Protection, or the Office of Refugee Resettlement," she adds.

Annunciation House's founder and executive director, Ruben Garcia, explained the philosophy of his work in 2020. "There is a tendency to look at hospitality as a work of charity, and indeed it is," he told the University of Notre Dame's Institute for Social Concerns podcast, Signs of the Times. "It is also a fundamental work of justice because when you offer hospitality, the true depth and meaning of hospitality is that you offer hospitality even when it may be at risk to oneself."

The families who helped Jews in Nazi Germany, the participants in the Underground Railroad who protected black people fleeing slavery, and the people who shield refugees "in the face of someone who says, 'You're violating the federal statutes under harboring, aiding, and abetting,'" Garcia explained, are performing "a fundamental act of justice. And ultimately, it is at the core of the Gospel."

"I see Annunciation House operating in this long legacy of migrant advocacy groups and religious shelters dating back several decades now," observes Barba. Like many of the churches that have helped migrants over the decades, Annunciation House now finds itself at odds with government officials.

'Stash House'

In February 2024, three representatives from Paxton's office arrived at Annunciation House with a "request to examine," an authority that allows the attorney general to investigate certain businesses and organizations. The OAG demanded Annunciation House turn over documents about its operations within one day—including, the nonprofit's lawyer has said, materials going back decades. The nonprofit was granted a temporary restraining order against the attorney general.

Undeterred, Paxton announced that he was suing Annunciation House "to revoke its registration to operate in Texas." His office "reviewed significant public record information strongly suggesting Annunciation House is engaged in legal violations such as facilitating illegal entry to the United States, alien harboring, human smuggling, and operating a stash house," a press release explained. The OAG "has complete and unlimited authority to examine business records to ensure that entities operating within the State are doing so lawfully," it continued.

Annunciation House rejects the argument that its work entices people to migrate illegally or otherwise break the law. "Nobody is walking for six months through the jungles of the Darién Gap and Central America and riding these trains to come and stay in our houses for a couple of nights and have a plate of rice and beans," Fontana says.

"We didn't politicize this," she adds. 'We're doing the work of the Gospel and it has become politicized….The politics have come to us."

Dominguez, the El Paso district court judge, proved sympathetic to that point of view. "The Texas Attorney General's use of the request to examine documents from Annunciation House was a pretext to justify its harassment of Annunciation House employees and the persons seeking refuge," he wrote in a July decision, granting the nonprofit's request to block Paxton's records demands. Paxton's efforts, Dominguez charged, were "unconstitutionally vague" and infringed on the nonprofit's "free exercise of religion."

"The Attorney General has a duty to uphold all laws, not just selectively interpret or misuse those that can be manipulated to advance his own personal beliefs or political agenda," Dominguez argued.

Though the decision was "a pretty ringing condemnation of the attorney general's case," Fontana says, "we felt pretty sure at that point" that Paxton wouldn't let the matter die. "This would continue to be a legal battle because it's such a political issue, and we see this as largely a political maneuver."

Sure enough, Paxton appealed the case. Rather than going to the Texas 8th Court of Appeals, he went directly to the Texas Supreme Court. He vowed "to vigorously enforce the law against any NGO engaging in criminal conduct."

Though Paxton paints the potential closure of Annunciation House as a way to restore order in Texas, Fontana argues that it would instead create chaos. "I really don't see how shutting down Annunciation House…would possibly do anything to curb illegal immigration," she says. "What it would do, immediately, is put a hundred or more people each day out on the street because they wouldn't have anywhere else to go."

"Instead of having a safe place to sleep, meals, and access to hygiene and basic medical care," she continues, "they would be left on a downtown street in El Paso with nothing but the clothes on their backs."

A New Model

Paxton and Annunciation House agree on one thing: The campaign against the nonprofit is part of a larger battle.

The federal government is constitutionally responsible for border enforcement. But as unauthorized crossings ballooned during Joe Biden's presidency, several states took it upon themselves to address what they saw as federal mismanagement of the issue. Texas has been arguably the most active player in this trend: The state government has bused over 100,000 migrants to blue cities, passed a bill allowing state law enforcement to arrest unauthorized border crossers, and deployed the state National Guard to keep the U.S. Border Patrol from accessing a stretch of the border in Eagle Pass.

Fontana sees a situation where "the federal government is on one page"—that is, it has "asked for Annunciation House's help and the help of other migrant aid organizations"—while the Texas government is on another, since it "wants to take a different line."

"I really see everything that's happened with the attorney general and Annunciation House as a continuation of the battle between the Texas state government and federal government over immigration policy," she continues.

The attorney general agrees that Annunciation House is caught up in its war against the federal government, though naturally he frames the issue differently. NGOs "facilitate astonishing horrors including human smuggling," said Paxton last February. "While the federal government perpetuates the lawlessness destroying this country, my office works day in and day out to hold these organizations responsible for worsening illegal immigration."

Though proponents paint the state-based model as a way to stick it to federal do-nothings, in reality it often threatens state residents' perfectly legal activities.

That's why many faith groups were vocal critics of Florida's Senate Bill 1718, which Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis marketed as a way "to crack down on the smuggling of illegal aliens." One measure would have made it a third-degree felony for Floridians to conceal, harbor, or shield—or transport "into or within" the state—someone who they know "or reasonably should know" is in the country unlawfully. The bill's sponsor, state Sen. Blaise Ingoglia (R–Spring Hill), claimed it was intended "to protect" Floridians "from the incompetence and unlawful open border policies of the Biden Administration."

Religious officials worried that S.B. 1718 could criminalize the everyday activities of churches, which often provide transportation services to members, including undocumented ones. Pastors wondered whether they would be risking felony convictions and jail time for driving parishioners to Sunday school or church services. Following the outcry, state lawmakers passed a version of the bill that stopped short of criminalizing the transportation of undocumented immigrants within Florida.

DeSantis cited "the Biden administration's failure to enforce federal immigration law" in a 2021 executive order barring the Florida Department of Children and Families from granting or renewing "any license for any family foster home, residential child-caring agency, or child-placing agency" that cares for unaccompanied migrant children. That move sent shock waves through faith communities too. Religious nonprofits urged DeSantis to walk back the order, with faith leaders arguing that it infringed on the activities of Christian foster parents and charities.

Imelda Maynard, director of legal services at Estrella del Paso, a Catholic ministry that provides free immigration legal assistance in West Texas and New Mexico, notes that Paxton's action has had "somewhat of a chilling effect" on her organization's activities "in that we're having to have a lot of contingency plans." This includes potentially seeking outside counsel if they get hit with a record request similar to what Annunciation House faced and "having to talk to staff about the need to not be quite so open and vocal about what we do."

Shortly before Reason spoke with Maynard last May, an Estrella del Paso client lost everything in a house fire. "We did not feel comfortable publicizing the need to help this person get back on their feet, because they were undocumented," Maynard says.

Paxton has repeatedly cited the Texas Religious Freedom Restoration Act in debates around religious liberties. But that law, which "prohibits a government agency from substantially burdening a person's free exercise of religion," would seem to defend Annunciation House's work. In his July decision, Dominguez said that Paxton's records request violated the act.

The battle between state and federal is also a battle between church and state, given that many of the groups and individuals burdened by these efforts help migrants as an expression of faith—and that battle shows no signs of subsiding.

'This Is Who Our Neighbor Is'

For now, the fate of Annunciation House rests with the Texas Supreme Court. Oral arguments are set for January.

The legal back-and-forth disrupted staffing at first. "We initially lost several of our long-term volunteers," notes Fontana, "because of their fears about what this would mean for the house." But the July decision brought a new wave of support. "We've had a number of people who have come to us because they've heard about us through the court case and they appreciated what we were doing," she says. "I think there is a general feeling among the volunteers who are with us now that we have really solid legal and moral standing to do the work that we're doing."

Staying in the fight isn't just about preserving Annunciation House's ability to serve undocumented immigrants in El Paso, says Fontana—it's about setting an example for other nonprofits that might come under fire, in Texas or elsewhere. "We have the resources and the profile to take a stand and fight that battle," she explains. "We're trying to sort of keep that culture alive and extend it by very publicly saying, 'We think we have the right to do this work and we're going to keep doing it.'"

Paxton has targeted several other organizations that aid migrants, including Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, which helps migrants and Texas residents alike. Catholic Charities provided more than 100 pages of documents in what its lawyers described as "a fishing expedition into a pond where no one has ever seen a fish." Paxton has also targeted Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, a legal services nonprofit, on consumer protection grounds. From January through September, Paxton investigated "at least five organizations…that do immigration-related work," The Texas Tribune reports.

Paxton is facing a bit of uncertainty himself. In October, a federal judge granted a permanent injunction halting the attorney general's use of the "request to examine" statute, which he had deployed to demand records from Annunciation House and other organizations. It was struck down in part because it required "immediate production of records under the threat of criminal prosecution," in the words of Bloomberg Law correspondent Ryan Autullo. That will likely have a big bearing on one of the two lawsuits Paxton is pursuing against Annunciation House.

Until the legal proceedings end, Annunciation House's day-to-day work will continue—and, Fontana says, it will still be informed by faith rather than politics.

"I do really feel—and we feel—that we're not doing this work out of political ideology, but a commitment to the dignity of the human person and a commitment to loving our neighbor and extending compassion to our neighbor," she says. "On the border, this is who our neighbor is."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "'The Politics Have Come to Us'."

Show Comments (34)