Throw the Bums Out

A wave of anti-incumbent sentiment is sweeping major democracies, as establishment parties run out of ideas that voters like.

Eight years ago this week, cartoonist Alex Norris posted a three-panel webcomic that was probably intended as a not-too-veiled comment on the 2016 election—but one that is even more relevant in today's political world.

In it, a character surrounded by furniture and various knickknacks declares "I want things to be different," and then proceeds to throw everything around the room. Now surrounded by a messy pile of broken stuff, the character delivers the punchline: "Oh no."

The one thing we can say for sure about 2024 is that voters worldwide want things to be different. Time will tell how that works out.

Donald Trump's victory and the Republican takeover of the U.S. Senate in this week's elections joined a remarkable trend of political turnover across the democratic world this year. The most interesting thing about that trend is the lack of any apparent ideological shift behind it.

Voters don't seem to be turning against progressive or conservative parties, and (despite how Tuesday's results in America look) the trend doesn't seem to be discernibly right or left. The Conservative Party got rocked in the United Kingdom's election this summer, as the left-wing Labour Party claimed a majority in Parliament for the first time since 2010. Meanwhile, Germany's Social Democrats (a left-wing party) got bulldozed in the European Parliamentary elections.

The trend continues beyond the U.S. and Europe, and includes a landslide defeat suffered by South Korea's conservative party in April, and the loss by South Africa's liberal African National Congress party, which had ruled for three decades (and was responsible for ending apartheid). Cast your gaze back to 2023, and the run of anti-establishment upsets includes the historic victory by Javier Milei in Argentina.

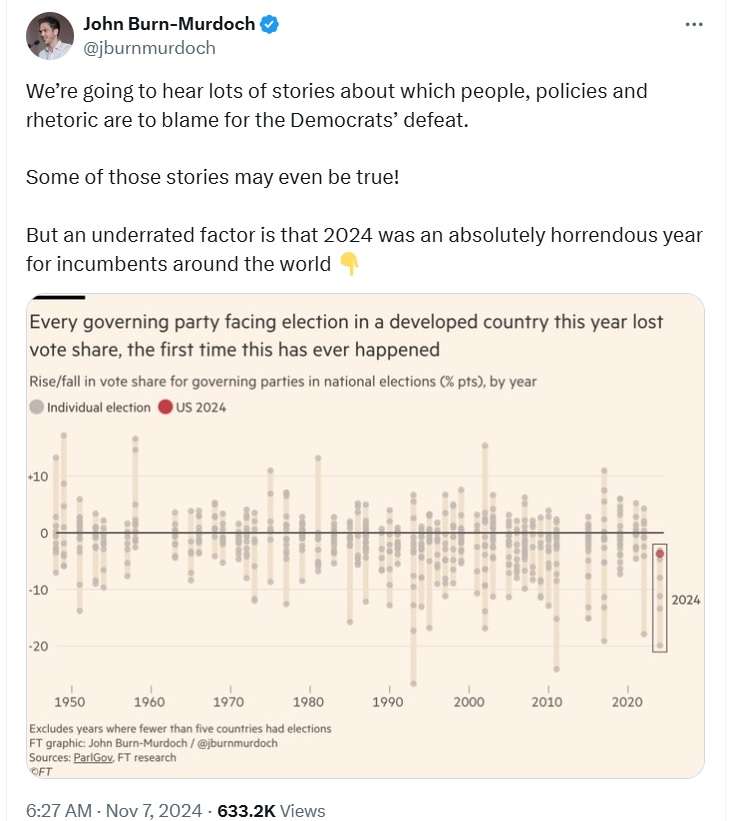

Even in places where ruling parties have stayed in power this year, they've earned a smaller share of the vote than in previous elections. That includes races in India, Japan, Belgium, Croatia, Bulgaria, and Lithuania, according to an analysis of election results by the Financial Times.

John Burn-Murdoch, the data reporter who crunched those numbers for the Financial Times, says this run of losses by incumbent parties is unprecedented in the modern world. "This isn't just the first time since [World War II] that all incumbent parties in developed countries lost vote share," he posted on X. "It's the first time since this data was first recorded in 1905. Essentially the first time in the history of democracy (universal suffrage began in 1894)."

Writing in The Atlantic in August, Derek Thompson identified this trend as the "downfall of the establishment, the disease of incumbency, a sweeping revolt against elites," and a legitimate threat to Vice President Kamala Harris' campaign. "Voters of the world are sick and tired of whoever's in charge," he concluded.

Simplistically, one might look at that global trend and use it as an excuse for Harris' defeat (and the Democrats' poor performance across the board) in this week's election. Is she merely the latest victim in a wave of anti-incumbent sentiment that has swept the democratic world in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic?

There's probably a better, deeper explanation. Burn-Murdoch's theory is that "people really hate inflation." That's probably a big part of it. Historically, sharply rising prices have been correlated with various episodes of social and political upheaval, as I've written about in the pages of Reason. Inflation breaks people's brains, and that anger tends to wash out ideological considerations that might guide voting preferences in more normal economic times.

The dissatisfaction that voters are registering with incumbent parties also probably reflects an ongoing problem across the democratic world—and one that Harris' campaign perfectly illustrated. Establishment parties seem to be out of big ideas, or at least out of big ideas that voters like.

Harris struggled to articulate anything that might be called a compelling vision for the future of the country. Economically, she tied herself to the failed "Bidenomics" that helped cause inflation. Beyond that, she offered little other than carefully calibrated clichés.

Trump, for all his many faults, certainly can't be accused of lacking big ideas. Unfortunately, some of them (like mass deportations) are morally appalling, while others (like tariffs) are likely to stoke even more dissatisfaction about rising prices.

We won't hit the end of the anti-incumbency trend in global politics until a party in power gives voters a reason to keep them there. That will likely require the political parties that emerged victoriously from the chaos of 2024 to look beyond the next campaign cycle and articulate an optimistic vision for a wealthier world.

I don't pretend to know what that will look like—but I'm deeply skeptical that the zero-sum, nostalgia-driven politics being offered by Republicans right now are it. Once in office, Trump will become the establishment and the countdown to voters turning on him will likely begin.

That's the thing about the "I want things to be different" moment: No one who gains power can expect to have it for very long. Rather than an excuse for Harris' loss, this global trend is better understood as a warning for those celebrating Trump's win.

Show Comments (26)