Newspaper Endorsements Die in Daylight

More than presidential politics or #AnticipatoryObedience, economics is to blame (or thank) for the long, slow death of a publishing anachronism.

It sure has been a banner week for the triple haters.

Just when you thought that Donald Trump had cornered the market on cringe by making groundwork-laying false claims about fraudulent Pennsylvania ballots, along comes a pro-Kamala Harris ad narrated by Julia Roberts telling fearful MAGA wives that they can sneakily vote Democrat, and then what's this? Joe Biden is still out there barking malarkey, this time about Trump's "garbage supporters"?

As if rising to the defense of its newly minted status as the most distrusted institution in America, the news media over the past few days has responded to the one-upsmanship of awful with a hearty "Hold my beer."

In an October surprise for the newspaper industry, first the L.A. Times, then USA Today, and most spectacularly The Washington Post all announced in these final days of the 2024 campaign that they were breaking with their tradition (very recent, in the case of USA Today) of endorsing a candidate for president. The fallout has been impressive: "At least 250,000" cancelled subscriptions at the Post (a 10 percent drop), a reported 18,000 more at the Times (5 percent range); staff resignations at both.

But what really ignited the triple haters—those with disdain for Democrats, Republicans, and the media—were the haughty, whither-democracy expressions of journalistic umbrage.

This "terrible mistake" is "an abandonment of the fundamental editorial convictions of the newspaper that we love," 21 Washington Post columnists wrote in a joint letter. "This is a moment for the institution to be making clear its commitment to democratic values, the rule of law and international alliances, and the threat that Donald Trump poses to them." Wrote L.A. Times Editorial Page Editor Mariel Garza in her resignation letter: "It makes us look craven and hypocritical, maybe even a bit sexist and racist….In these dangerous times, staying silent isn't just indifference, it is complicity." (The San Francisco Press Club on Tuesday bestowed to Garza its first-ever Integrity in Journalism Award.)

Similar noises could be heard everywhere from former Post editor Marty Baron ("this is cowardice, with democracy as its casualty"), to former Baltimore Sun reporter-turned-TV writer David Simon ("this kind of abuse of a public trust by a publisher is unacceptable"), to the new trending Twitter hashtag #AnticipatoryObedience. (Sample, from Protect Democracy founder Ian Bassin: "Trump hasn't even won and media outlets from @washingtonpost to @latimes to @CNN to more are already engaged in #AnticipatoryObedience. Terrifying trajectory for press freedom and independence if he actually returns to power.")

Terrifying, or unintentionally hilarious depending on your vantage point. "There is literally nothing funnier in the known universe," cracked Twitter wag Dave "Iowahawk" Burge, "than journalists' sense of self-importance."

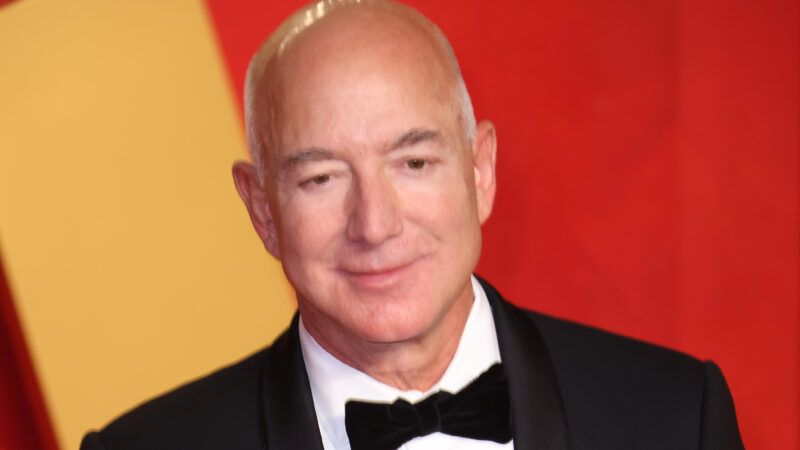

As per usual in media controversies, reactions to the wave of non-endorsements have fallen largely along political lines. Conservatives, libertarians, and centrists nodded vigorously at Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos's explanation that "presidential endorsements…create a perception of bias," and that "most people believe the media is biased. Anyone who doesn't see this is paying scant attention to reality, and those who fight reality lose." Journalists and left-leaners, meanwhile, warned of "looming autocracy" and asserted connect-the-dot observations as explanatory fact.

"Trump waited to make sure that Bezos did what he said he was going to do, and then met with the Blue Origin people," longtime opinion page hand Robert Kagan told The Daily Beast, referring to the Bezos-owned space company. "Which tells us that there was an actual deal made, meaning that Bezos communicated, or through his people, communicated directly with Trump, and they set up this quid pro quo." (Bezos said he had no prior knowledge of the Blue Origin meeting, and that "Neither campaign nor candidate was consulted or informed at any level or in any way about this decision.")

Overshadowed as ever in the politicized ruckus is the basic economic fact that the newspaper business has collapsed by about 75 percent since 1990 across all measures (circulation, revenue, staffing); and is now hemorrhaging money after decades of 20 percent profit margins. (The Post in 2023 alone lost $77 million.) In an industry desperate to shed expenses, arguably the most cost-ineffective section of the entire newspaper is the one being so bitterly fought over this week: unsigned editorials.

When Michael Kinsley took over the L.A. Times opinion pages in 2004, he infamously (within the paper, anyway) prepared a PowerPoint presentation on "pie-in-the-sky" ideas to be discussed at a company management retreat. Included among those thought bubbles was axing unsigned editorials altogether, a proposal that proved awkward internally when he left a copy of his presentation near the office printer.

But the economic logic as laid out by Kinsley was not just brutal, but inevitable. The L.A. Times editorial board, which I was hired for in 2006 very soon after the former Slate editor was axed, had at the time of his PowerPoint around 15 members, who between them were responsible for around 20 unsigned editorials a week at about 400 words each. Some of those employees had other editing and writing responsibilities, but several others did not. With the kind of salaries that would make 99 percent of L.A. freelancers physically ill with envy, the section's effective dollar-per-word rate approached peak-era Vanity Fair.

These are the kinds of luxuries you can afford when you're the most profitable newspaper in the history of the world—less so when you're bleeding $40 million per year. And those numbers look even worse when you account for measurable impact (including readership) of the editorials themselves.

In an informative Poynter piece that lamented the long-term non-endorsement trend, Rick Edmonds nonetheless offered several good explanations for its rise, including: "At Gannett [owner of USA Today and more than 100 other newspapers], extensive studies found that editorials, at least in digital format, were among the least-read content," and "Studies have shown that a news outlet endorsement has little impact on how people vote," and "No matter how many times the clarification is offered that an editorial board and the newsroom operate separately, many readers don't see the distinction or don't believe there is one."

Donald Trump won 46.8 percent of the national vote in 2020 after daily newspapers had overwhelmingly endorsed his opponent, Joe Biden, by a Wikipedia-collated count of 107 to 14 (with one anyone-but-Trump). He won 46.1 percent of the vote in 2016 when newspapers lopsidedly preferred Hillary Clinton 244 to 20 (with Libertarian Gary Johnson receiving 9 and independent Evan McMullin one). He is currently polling at 47.5 percent as a lower count of dailies nonetheless maintain the same basic ratio: 40 to 6 as of Thursday morning.

All of which is a far cry from where the sentiment of newspaper ownership—which traditionally has been the deciding force in unsigned-editorial slant, as opposed to the more separately managed newsroom—has traditionally been. Republican Richard Nixon, for example, won the 1972 endorsement war in nearly as big a landslide as the Electoral College tally: 753 to 56. Though it is also true, as I laid out in this 2018 article, that both the Nixon administration and the media ownership class were openly reminding one another about the connection between editorial content and executive-branch decision-making.

As my former L.A. Times colleague Robert Greene (who I have tremendous professional respect for) wrote this week in The Atlantic in a piece explaining his resignation:

The Times editorial board went more than three decades without endorsing in presidential races, largely because readers and the newsroom were so outraged by the endorsement of Richard Nixon for reelection in 1972 that publishers were too cautious (or rather, too chicken) to again take a stand. But soon after I arrived at the Times, the editorial board promised to start endorsing for president again in the 2008 primary.

Nixon won his home state of California by 13.5 percentage points; one of nine GOP wins in the Golden State in the 10 presidential elections between 1952 and 1988. But 1972—and its immediate aftermath of the Watergate investigation, Nixon's resignation, and the valorization of the journalistic role thereof—was a political inflection point in newspaperdom.

The American Journalist Survey, a decennial industry study operated out of Indiana University, has found that the self-reported political party identification of working journalists has shifted massively leftward during the past half century: From a ratio of three Democrats to two Republicans in 1971 (35.5 percent to 25.7 percent, with 32.5 percent independent and 6.3 percent other), to 11:1 in 2022 (36.4 percent to 3.4 percent).

The Trump era, which journalists have responded to with calls for the "moral clarity" of rejecting "bothsidesism" in the name of protecting democracy, has only accelerated this long ideological drift. When you combine political polarization with a collapsing business model, the loudest cost centers are going to be the first to go.

As with the decline of many local institutions, from church to Little League to social clubs, there is some unreplicable loss associated with the demise of editorial boards. Though definitionally insular (I tried in my small way to share our newsmaker conversations with the public), they served as a way for the local and sometimes national political class to check one another, deliver progress reports, argue ideas. When I spoke with the then-L.A. Times publisher in 2008 about potentially returning to run the page, and he wondered aloud—Michael Kinsley-style—about the value of continuing unsigned editorials, I blinked rather than reach for the axe. Like the canned peaches at town meetings in the classic HBO show Deadwood, there was some mystery in the civic ritual that I felt too conservative to toss aside.

But kiloliters of red ink have spilled since then. What you're hearing this week is the thrashing of an old whale yanked rudely from the sea and dumped unceremoniously onto the sand: It will be loud, not particularly dignified, and will soon die. Bezos and company managed all of this poorly—this decision should have been made in spring, not October—but as the last generation of non-vulture capitalists willing to bet on the newspaper business, they acknowledged what many journalists still cannot: Those glory days are over.

Show Comments (95)