Dispatch From Israel: Inside the Hope Machine

Conversations with a coalition of Israelis who aren’t willing to wait for the government to get their loved ones back after October 7

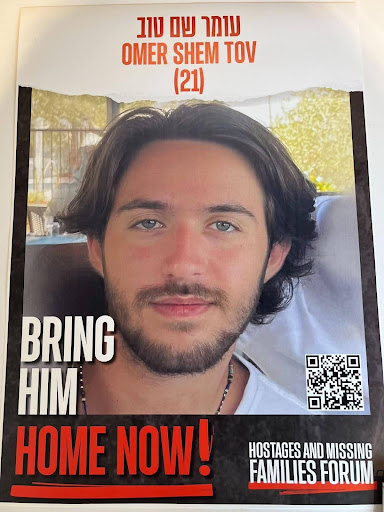

When the alarms sounded at 6:30 a.m. on October 7 near her home in central Israel, Shelly Shem Tov was not immediately concerned. "We are in a crazy country where the bombs are regular," she told herself. Nevertheless, Shem Tov called her son Omer, 21, whom she'd seen the day before—her 50th birthday—shortly before he headed off to a music festival. Her youngest child assured her he was fine. Then Omer called back, he and his friends were trying to escape; they were running for the car. Shem Tov tracked her son on his phone and could see his location live. Something wasn't right; the car was going in the wrong direction, into Gaza.

By midday on October 7, Emilie Moatti's phone was exploding with messages from people all over the world asking what they could do to help. The onetime member of the Knesset for the Israeli Labor Party and peace activist did not yet have any idea of the size and scope of the catastrophe. What she did know, because she knew the actors in the government, was that nothing was going to happen if she didn't do something. "Call your colleagues," she told her husband Daniel Shek, the former Israeli ambassador to France. "Tell them to come home. We are starting a headquarters."

On October 8, Rebecca Shafrir and her husband Gideon were watching a news program from their apartment in Tel Aviv, an interview with Hadas Calderon, whose two children had been taken hostage. A fourth-generation Israeli, Gideon wondered how this could happen in the most protected country with the most capable military and, also, why wasn't this being handled? Shafrir, who had experience as a fundraiser,* knew she had to either start handling it or fight with her husband. She started making calls.

There is no road map for what to do when your child is abducted by terrorists; when 1,400 of your countrymen are slaughtered and hundreds of others kidnapped; when the world variously shows sympathy or skepticism; when local authorities are too swamped or self-interested to reach out. Shem Tov, in fact, did not hear from any state official until days after she'd seen a video of Omer on the floor of a pickup truck, his hands cuffed.

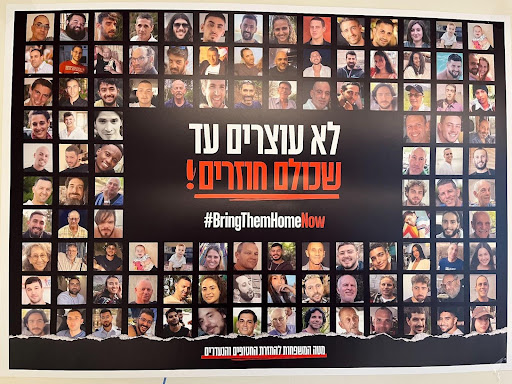

"This is how I help; this is how I don't go crazy," she says of spending 12 hours a day at Hostages and Missing Families Forum in Tel Aviv, an organization formed by a handful of Israelis within 48 hours of the October 7 massacre. It's a space where people can bring their sorrow and industry: Bakers bake bread, the rich give cash, and citizens—2000 to date, all volunteers—set up tents in a square within sight of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) headquarters. There, hostage families can rest and protest to ensure their loved ones are not forgotten, a 21st-century version of "making the desert bloom," born of a similar refusal to give in to desperation and the death their neighbors might wish for them.

"This is an entirely civilian operation, a grassroots sort of pop-up," says Shafrir. The forum is currently operating out of a six-story building donated by an Israeli security company, all expenses paid for a year. In mid-January, the halls of the forum are in constant motion, lawyers speaking with representatives from the Hague; holistic practitioners massaging the bedraggled; Emmy- and Israeli Academy Award–winning filmmakers creating marketing campaigns; and IDF reservists with siblings held in Gaza ducking questions from nosy reporters.

"I think that everybody needs to do what they know how to do best," says Dorit Gvili, COO of the advertising agency Publicis One Israel. Before October 7, Gvili spent her days "selling people shampoo and cars and beautiful stuff." Now she coordinates teams making videos, logos, billboards, and social media posts, anything to keep the hostages in the public eye.

"When Seinfeld came, I told him, 'You don't have the best creative team, I have the best creative team!" she says of comedian Jerry Seinfeld dropping in during a recent trip to Israel, one of an uncounted number of people who come to express support and, sometimes, astonishment.

"I had a guy here from Ukraine. He told me, 'You succeed to do so much noise for 250 [hostages]. We had 20,000 children abducted by Russia, and nobody knows,'" Gvili recalls. "So yes, people are still talking about us. We're giving them reason to talk about us. It's not yesterday's news. And three months into the situation, it's still only volunteers, no government."

Nor have politicians shown interest. "The new minister of foreign health came last week for the first time," says Moatti. When asked whether Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has come by, Moatti gets sly.

"I'm not sure he was invited," she says.

Shafrir says the prime minister has been invited, including to speak at a rally commemorating the hostages' 100 days in captivity. "He refused. No one from the government spoke, no one wants to be associated with us," she says. "They want to say, 'You stop the war or get the hostages, not both.' But we can do both. We can get the hostages and then stop the war."

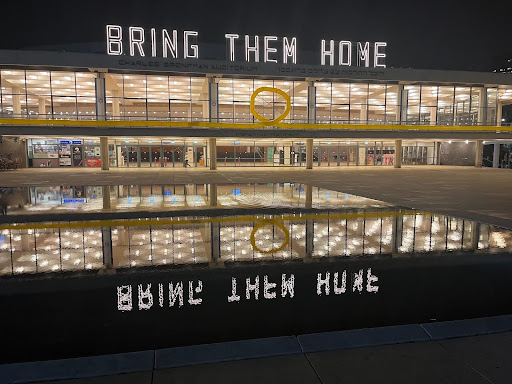

How do you do this? If you're a pizza-maker from Haifa, a cartoonist from Jerusalem, or a mother from Herzliya living in terror not, as Shem Tov says, "every day, every hour, but every minute," you show up. You build an art installation tunnel simulating the hostage experience. You man the merchandise room selling BRING THEM HOME NOW sweatshirts and dog tags, you attend the Saturday night rallies where 20,000 people chant "ACH-SHAV! ACH-SHAV!" ("Now! Now!") You wonder aloud when the goddamn Red Cross is going to get medical supplies to what are believed to be 136 people still held in Gaza. You do anything to keep the hostages' names on people's lips, and you absolutely do not give in to the idea that you cannot bring them home. You stay inside the hope machine you have built, the one that whirrs loud enough to keep bad eventualities at bay, so long as you keep feeding it.

And they do. The enterprise creates a glue that keeps people at their desks. After dark, it brings them up to the roof deck, where despair is transmogrified into a noisy party, complete with homemade pizza made by local chefs. At 9 p.m., no one is making a move to leave.

"It's like 'Hotel California,'" says Gideon, who's stopped by to see his now-never-home wife.

A designer pours from a bottle of red wine and suggests that when all the hostages are freed, the forum keep going, maybe dedicate their efforts to finding the missing Ukrainian children.

This is not the goal of ad agency exec Gvili.

"Our dream from Day One is that this organization will be closed," she says. "Then I can get back to doing the new Charlotte Tilbury lipstick review. That should be my problem."

*CORRECTION: The original version of this article mischaracterized Shafrir's fundraising background.

Show Comments (44)