When Your Heart Becomes a Snitch

Modern medical devices are lifesavers. But they’re vulnerable to hackers and compromise our privacy.

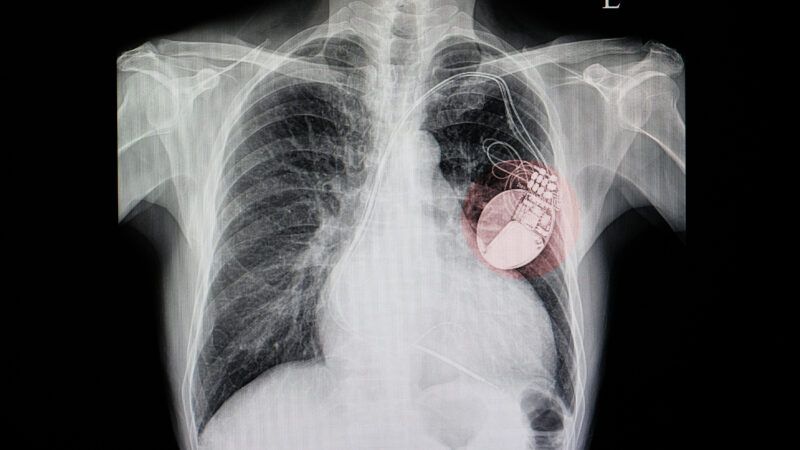

Given how much I write about privacy, it's a little surprising that I now have a radio transmitter in my chest. But that's the sort of thing that happens when you walk into an emergency room with a heart rate that won't go above 30 and the next day roll out of surgery after the emergency implant of a cardiac pacemaker. That pacemaker is equipped with radio frequency telemetry that allows it to transmit details about my health to medical providers and to be fine-tuned by a technician.

The device keeps me going, but it also disturbs the hell out of me.

You are reading The Rattler from J.D. Tuccille and Reason. Get more of J.D.'s commentary on government overreach and threats to everyday liberty.

Millions of Wired Americans

Somewhere around 3 million Americans have cardiac pacemakers, which electrically regulate slow heart rates, while many others have implantable cardioverter defibrillators which stop arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats). Some have a combination of the two.

Increasingly, the devices are remotely accessible so that they can transmit health data to medical professionals and be fine-tuned for the needs of specific patients. In practice, that can be both fascinating and helpful; after I walked up and down the hallway, a representative of the manufacturer used a tablet to remotely tweak my pacemaker settings to be more responsive to my level of exertion. Athletes often have their pacemakers set differently for competitions than for everyday life, he told me.

From time to time, a base station next to my bed automatically queries my pacemaker, downloads stored information about my heart function, and sends it off through the cell network to be reviewed.

My Hackable Heart

But a medical device that can be remotely accessed for good reasons is also potentially vulnerable to malicious intrusions. The tradeoffs between the lifesaving potential of remotely accessible medical devices and the vulnerability of technology have been discussed for years—though concerns sometimes get steamrolled.

Fifteen years ago, a journal article pointed out that researchers "partially reversed the ICD's [implantable cardioverter defibrillator] communications protocol with an oscilloscope and a software radio" and then "performed several software radio-based attacks that were able to retrieve uncrypted personal patient data, as well as change device settings."

The authors added that "it is believed that the risk of unauthorized access to an ICD is unlikely, given the considerable technical expertise required."

Well, all sorts of things are unlikely right up until they're done. In 2017, the FDA issued a notice that 465,000 pacemakers made by Abbott/St. Jude's Medical had "cybersecurity vulnerabilities" that "could allow an unauthorized user (i.e. someone other than the patient's physician) to access a patient's device using commercially available equipment." Worse, somebody gaining access to the devices could "modify programming commands to the implanted pacemaker, which could result in patient harm from rapid battery depletion or administration of inappropriate pacing."

The fix, as is often the case with hackable technology, was a firmware update.

A year later, Ars Technica reported that "pacemakers manufactured by Medtronic don't rely on encryption to safeguard firmware updates, a failing that makes it possible for hackers to remotely install malicious wares that threaten patients' lives." The vulnerability was revealed at the Black Hat security conference and resulted in another FDA notice.

By that time, the Homeland TV show had already featured the assassination of a fictional U.S. vice president via hacked cardiac pacemaker.

"While the experts concur that a malicious Homeland-like attack on RF-based implants is unlikely, and some manufacturers have made great strides in protecting their products from wireless breaches, implantable device security is still a matter of utmost concern," Jim Pomager, Med Device Online's executive editor, wrote in 2013. "Ignore cybersecurity and it will invariably come back to haunt you, whether it's in the form of a lawsuit, a letter from the FDA, or the embarrassment (and bad press) of a hacker exposing your device's flaws on an international stage."

That, of course, was several years before the revelations about Abbott and Medtronic pacemaker vulnerabilities. The race between hackers and security professionals continues.

When It's a Feature, Not a Bug

But the vulnerabilities of medical devices are a side effect of the remote access capabilities deliberately designed into the devices so that medical professionals, such as my cardiologist, can pull up data and monitor patient health. The range of intentional uses of such access can also veer into disturbing areas.

In Congress, the Support for Patients and Communities Reauthorization Act includes language providing for "a study on the effects of remote monitoring on individuals who are prescribed opioids." The language in the bill, which was passed by the House last month, is part of a trend towards addressing behavior the powers-that-be don't like—among them, drug use—through surveillance.

"A government‐sanctioned study like the proposed one by GAO will no doubt show that, given current or projected technologies, it is possible to remotely monitor how patients use opioids through their physiological responses," warned Jeffrey A. Singer and Patrick G. Eddington for the Cato Institute. "With such data in hand, misinformed anti‐opioid crusaders in Congress will then take the next 'logical' step — legislation requiring all patients prescribed opioids for any reason to be remotely monitored (another example of 'cops practicing medicine.')"

That's not where I'm at with my pacemaker. But I have a cardiologist who already told me he thinks I exercise too much. Is he going to review the data and second-guess my habits? Is my snitching medical device going to inspire nagging sessions with doctors, perhaps followed by nastygrams from my insurance company or government agencies about lifestyle choices and resulting costs? Technological capabilities are racing ahead, but conversations about the implications lag well behind.

That's a thought to make my heart race.

For the time being, so soon removed from the cardiovascular intensive care unit, my base station remains bedside, relaying data from my pacemaker to whoever is on the other end. But while it saved my life, I have yet to make peace with a medical device that reports my heart health for review and revision.

Show Comments (265)