Football Eye Black Isn't Blackface

A student’s overzealous school spirit shouldn't ruin his life.

When La Jolla High School played Morse High School under the Friday night lights on October 13, students from the surrounding San Diego area filled the stadium to cheer on their prospective teams. Making posters, dawning face and body paint, yelling chants, and sporting jerseys were all part of the electric football game atmosphere.

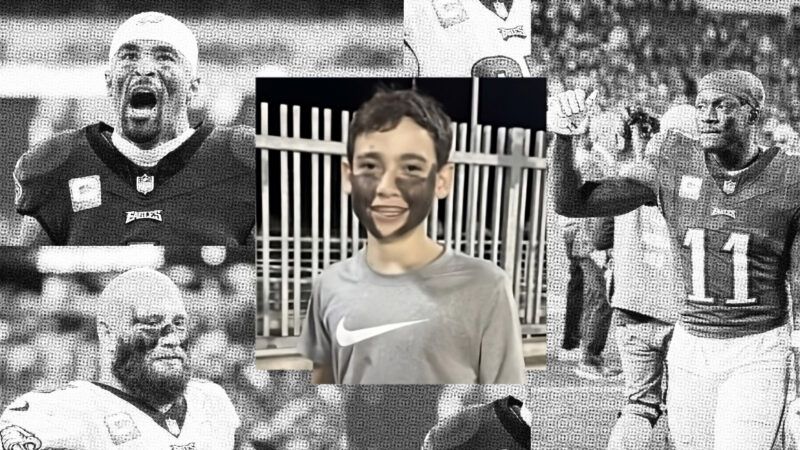

J.A., a middle-schooler from Muirlands Middle School, attended the game with another student and that student's mother. To show support for his team, J.A. let his friend put eye black paint on his face. A security guard even complimented the design. The game was largely uneventful with La Jolla winning handedly (56–6). But almost a week later, J.A. was called into a disciplinary meeting with his parents at Muirlands.

In that meeting, J.A. was told he would be suspended from school for two days and was no longer allowed to attend future athletic events because he wore "blackface" to the football game. The suspension notice only specified that he was being suspended because he "painted his face black at a football game," and the alleged offense was marked as "Offensive comment, intent to harm." J.A.'s father told the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), a First Amendment nonprofit, that no one complained or said anything negative about his son's eye black while at the game. The school's principal also failed to specify how they found out about the incident.

As Aaron Terr, director of public advocacy at FIRE, notes in a November 8 letter to Muirlands Middle School, "J.A.'s non-disruptive, objectively inoffensive" face paint is absolutely constitutionally protected expression.

In the letter, FIRE reminds school officials that "public school students do not shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate." It argues that "the First Amendment protects J.A.'s non-disruptive expression of team spirit via a style commonly used by athletes and fans."

Eye black applied under the eyes and even on the cheeks is not blackface, and to suggest as such is a gross mischaracterization. Blackface is dark makeup applied all over the face to mimic, exaggerate, and mock black people. J.A. was simply cheering on his local football team with friends—and there is no reason to punish him for that.

In the 1930s, Babe Ruth was the first professional athlete seen wearing eye black. Ruth believed that black grease worn under the eyes blocked out the sun's glare during games. Now athletes may wear eye black to prevent glare, to hype themselves up, or maybe just because they are superstitious. And fans wear it to show support and spirit for their beloved teams—just like they would wear a hat, jersey, or even body paint.

I proudly wore eye black for water polo games and swim meets in high school. We called it "war paint." And last Sunday, while I jumped, cheered, and booed at Lincoln Financial Field while the Philadelphia Eagles faced off against the Dallas Cowboys, it was hard to find a player not wearing eye black.

"Muirlands Middle School administrators should make time this Sunday to watch a few NFL games," Terr tells Reason. "Maybe then they will realize that athletes and fans often liberally smear eye black on their faces, whether to look cool, show team spirit, or intimidate their opponents. The student engaged in a fun and harmless form of self-expression."

FIRE is calling on Muirlands to lift the ban on J.A.'s attendance at future athletic events and to remove the infraction from his record.

Show Comments (84)