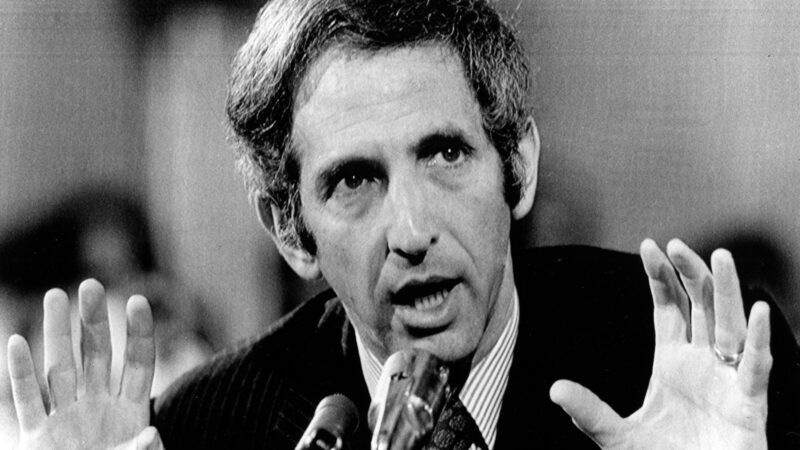

RIP Daniel Ellsberg, Who Told the World the Truth About the Vietnam War

The Pentagon Papers leaker risked prison to reveal that American military officials were lying to Congress and the public about Vietnam. He died today at age 92.

Daniel Ellsberg was in the midst of a federal trial, facing the prospect of a long prison term, when he sat down with Reason in the summer of 1973 to talk about his decision to leak a trove of documents. Those documents, known as the Pentagon Papers, showed that top American officials, including President Lyndon Johnson, had lied constantly about the country's war in Vietnam.

"The only thing that I could personally hope to achieve by my own efforts was to make these documents available to the American public for them to read and to learn from," Ellsberg told Reason. But he had a "very important secondary objective": halting what he saw as a dangerous trend of "executive secrecy" that had allowed successive presidents to "steal away so much power from the Congress and the public and to free itself from the kinds of checks and balances that were intended in the Constitution."

By giving those 7,000 pages to The New York Times two years earlier, Ellsberg changed the course of a war and shifted the American public's view of the presidency. He may not have succeeded in the larger project of containing executive power, but he earned a place in the whistleblower hall of fame: one of a select few who, when entrusted with damning secrets, recognized that his patriotic duty was to tell the American people a difficult truth their leaders would rather have kept hidden.

Ellsberg died Friday at his home in Kensington, California, according to multiple media reports, after a monthslong bout with inoperable pancreatic cancer. He was 92.

Though the Pentagon Papers exposed a myriad of official lies about America's role in the Vietnam War, the big lie at the center of it was one that sounds all too familiar to those of us who came of political age during the post-9/11 wars: that America was winning. Privately, top military officials, including Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, knew this was not true. From his post at the RAND Corporation, Ellsberg obtained access to reports from 1967 and 1968 showing that the best-case scenario was a long-term stalemate—a stalemate that would eventually kill more than 58,000 Americans and more than 2 million civilians in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

It was a trip to Saigon in 1965 as one of McNamara's advisers that first suggested to Ellsberg that something was wrong. After witnessing the chaos of the war firsthand, Ellsberg—a Harvard graduate and former Marine—tried to work within the system to change American policy. In 1970, after photocopying the secret Pentagon report that would make up the bulk of the Papers, he gave partial copies to several high-ranking senators. The effort went nowhere, leading Ellsberg to eventually leak the full report to a Times reporter, Neil Sheehan.

"A system that allows some secrets has to be a limited one, because relatively few secrets can be kept from the American people if we are to remain a democracy; and it must have safeguards built in against the abuse of it," Ellsberg told Reason in that 1973 interview. "You come down to the principle that no one man, even the President, should be allowed to decide without review that certain kinds of information cannot be known to American citizens."

Ellsberg was arrested for espionage, conspiracy, and other charges that could have meant a lifetime behind bars. He escaped prosecution due to some of the same executive overreach that had inspired him to leak the documents in the first place. The Nixon administration sent operatives—the same ones later implicated in the Watergate scandal—to break into Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office, and the FBI illegally wiretapped his phone. When this misconduct came out, Judge William Byrne dismissed all the charges against him.

Ellsberg remained an outspoken anti-war activist for the rest of his life. He warned frequently of the dangers of nuclear annihilation. Two years ago, he released another secret government study that he'd photocopied long ago: a 1958 plan for a nuclear strike against China in retaliation for shelling Taiwan.

He opposed the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq—"What we've done to the Middle East has been hell," he said in 2018—and criticized the post-9/11 increases in executive power and secret-keeping.

When Edward Snowden leaked details of the National Security Agency's domestic spying regime in 2013, Ellsberg was effusive in his praise. "In my estimation, there has not been in American history a more important leak than Edward Snowden's release of NSA material—and that definitely includes the Pentagon Papers 40 years ago. Snowden's whistleblowing gives us the possibility to roll back a key part of what has amounted to an 'executive coup' against the US Constitution," Ellsberg wrote in The Guardian.

In an era of unprecedented levels of executive power and an ever-expanding national security state, America and the world could use more people like Ellsberg, who was willing to prioritize the truth over all else.

In his final interview with Reason, conducted in 2017, Lucy Steigerwald asked Ellsberg to consider his legacy.

"I would like others to believe that they have the power—and the obligation, really—as patriots, as human beings, to reveal what they themselves know are unjustified dangers to human existence," he said. "And not simply, for reasons of career and promises to superiors, to conceal dangers of that nature. In other words, to be truth tellers."

Show Comments (54)