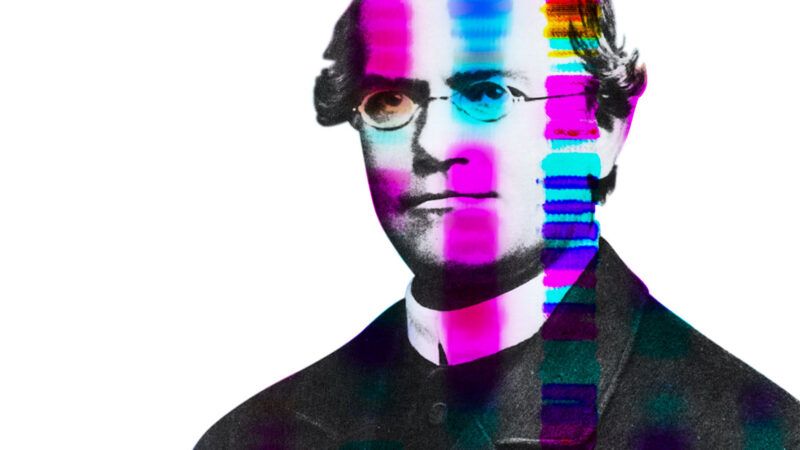

Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics and a Tax Resister, Turns 200

Mendel had a history of run-ins with the state.

Two hundred years ago in July, Johann Mendel was born. He would come to be known as Gregor (the religious name he received upon entering the Augustinian Friars at St. Thomas' Abbey in Austria-Hungary) and later as the "father of modern genetics."

Mendel studied math, physics, and eventually botany in school. While conducting experiments with hybridized pea plants in the monastery garden and greenhouse, he discovered the principles of heredity. His process involved carefully tracking various traits, such as pod shape and plant height. From those observations, he developed a theory involving what he called dominant and recessive "factors"—what would come to be known as "genes."

This work paved the way for all future research in the genetic sciences, including the discovery of DNA. But Mendel's contributions would not be recognized in his lifetime.

In 1866, Mendel published the results of his experiments. The paper received little attention. In 1868, Mendel was named abbot (head monk) of his monastery, and his research gave way to administrative obligations. He died in 1884.

Things began to change in 1900. That year, a British biologist named William Bateson unearthed Mendel's paper. He translated it into English and became a proponent of Mendel's ideas. Bateson's own experiments extended Mendel's discoveries, showing, for example, that Mendelian principles applied to animals as well as plants. Bateson also bestowed the name genetics on this area of study. Today, Mendel is widely recognized as "the architect of genetic experimental and statistical analysis," as the Encyclopedia Britannica puts it.

Biographies of Mendel note a history of run-ins with the state. When he first arrived at St. Thomas' Abbey, he was assigned to a teaching job. But the Austro-Hungarian government around that time began requiring an exam for teacher certification. Mendel, who suffered from severe test anxiety, attempted the exam on two occasions, six years apart, and failed it both times.

Two decades later, as abbot, Mendel again found himself at loggerheads with the authorities after a new city law attempted to subject the monastery to heavy taxation. "The very idea made Mendel boil," writes Robin Marantz Henig in The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics. "The abbot began a single-handed letter-writing campaign," which became "more detailed, more impassioned, more strident, and more vituperative as the years went on." Henig adds that "the stubborn abbot never wavered in his insistence that a tax on church property was unconstitutional."

The battle lasted until Mendel's death a decade later. He never did agree to pay the tax.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Father of Genetics Turns 200."

Show Comments (27)