This Renegade California Developer Wants To Build a 2,300-Unit Megaproject in a NIMBY Stronghold

A never-before-used state law might make his plans bulletproof.

Shortly after news broke that Los Angeles developer Leo Pustilnikov was intent on acquiring and converting an aging power plant in the beachside community of Redondo Beach, California, into new shops and apartments, a business acquaintance offered him a strange form of congratulations.

"You must be smarter than me," the acquaintance told Pustilnikov at a New Year's event in the city's harbor, he recounts to Reason.

"Why?" asked Pustilnikov.

"Because Redondo only fucked me for $1 million," the friend responded. His point was not that the city was an easy place to build things.

Redondo Beach has developed a reputation as a growth-skeptical—its critics would say "not in my backyard" (NIMBY)—stronghold in Los Angeles and the state generally.

It's a place where local activists have called for erecting a "firewall" against unwanted development, and the typical home goes for $1.5 million. Despite occupying 1.5 miles of prime coastline along Santa Monica Bay, only 1,000 new homes have been permitted there within the past decade, according to federal permitting data.

A focal point for this growth opposition has been the gas-powered, smoke-belching AES power plant that's long been slated for closure. Its World War II–era technology sits idle most of the time. Environmentalists have taken issue with its use of ocean water to cool equipment, which damages marine life.

While state officials have kept pushing back the plant's closure date—arguing California's power grid needs all the spare capacity it can get—local residents, developers, and city officials have been sparring over what to replace it with.

The 51-acre, ocean-abutting site is an irresistible prize for builders. When the former AES plant owners put the property on the market in 2016, it attracted over 200 offers with already-signed confidentiality agreements, reported CoStar in 2020. A successful listing typically attracts 20 or 30 such offers.

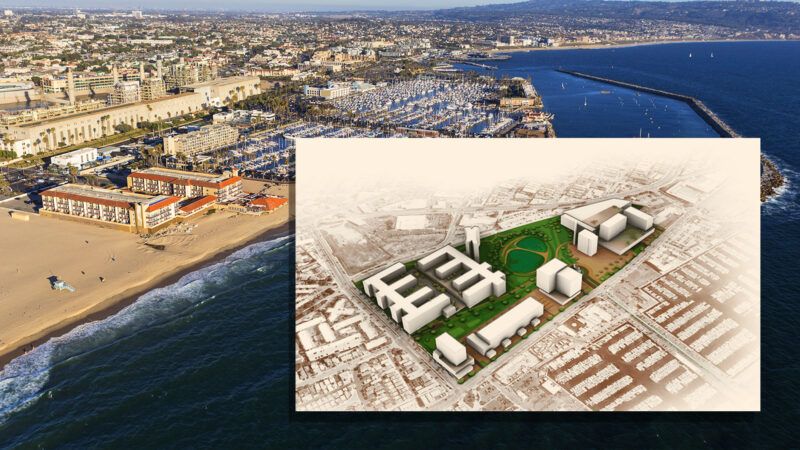

"How many 50-acre sites do you have across the street from the water in a dense community adjacent to beaches and parks?" says Pustilnikov, who finalized the acquisition of the site that year for a reported $150 million.

Local "yes in my backyard" (YIMBY) activists have likewise argued in letters to the city that it's the perfect place to fit new housing without displacing existing residents and businesses.

Opposing that vision are many Redondo Beach residents and most of their elected officials. Six times now, city voters have passed referendums that either stopped commercial and residential development there or endorsed replacing the AES plant with a park instead.

"This is the worst place for residential, as there are no ways for the residents to go to their jobs," says Redondo Beach City Council Member Nils Nehrenheim, warning of nightmarish congestion if the site is turned into new housing. "What we need here is balanced development in Redondo Beach as a whole. We are park-poor because we are so dense."

This anti-development fervor suggests Pustilnikov would be pretty crazy, and certainly unsuccessful, for trying to put a 3-million-square-foot megaproject there. Yet, this is exactly what he's proposing.

In an application filed August 10, and first reported on by the local Daily Breeze, several companies linked to Pustilnikov and his business partner Ely Dromy requested permission to build a massive project called One Redondo. It would feature residential towers up to 200 feet tall, containing a total of 2,290 units. That would be complemented by roughly 800,000 square feet of office, commercial, and hotel space, and over 5,000 parking spaces.

Their application frankly acknowledges that housing "is not currently featured as a permitted or conditionally permitted use" on the site. But that's OK, they say, because nearly 500 units in the new development would be affordable apartments provided at below-market rates to low-income residents.

The inclusion of those affordable units triggers a never-before-used but potentially game-changing provision in California law called the "builder's remedy" that could make Pustilnikov's One Redondo project bulletproof to local opposition.

Despite its well-justified reputation for wrapping new housing construction in paralyzing red tape, California has several longstanding laws on the books that are intended to thwart local governments' throttling of new development.

That includes a requirement that cities periodically produce plans showing how they'll change their zoning laws to meet state-set housing production targets. The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) is responsible for setting those targets and then certifying that localities have come up with realistic plans, called "housing elements," for meeting them.

The state also created the builder's remedy to ensure housing gets built even if a local government fails to produce that housing element or allow enough housing to meet those targets.

In theory, the builder's remedy permits developers to construct projects of unlimited density anywhere in a city without an HCD-certified housing element, regardless of what the local government's zoning code says. Provided at least 20 percent of the new units are affordable for low-income renters or buyers, the city government can't say no to it.

This is exactly what Pustilnikov is trying to do in Redondo Beach.

The city had an October 2021 deadline for adopting a housing element that would allow for roughly 2,500 new homes. But the plan the city council approved was rejected by the HCD for not realistically meeting that target. In particular, the department took issue with the city projecting that existing offices and businesses would be shortly redeveloped into housing.

The city revised and resubmitted its housing element, which was rejected by the HCD again in April.

Enter Pustilnikov and his development partners. In August, they filed an application for the 2,300-unit project at the AES site. If it's approved, One Redondo will be the first successful builder's remedy project in California history. (Pustilnikov has a pending application for another builder's remedy project in Santa Monica.)

Despite the builder's remedy having been on the books since 1990, developers have universally shied away from its awesome red tape–cutting potential. A few reasons explain their hesitancy.

The housing element process that can trigger a builder's remedy has largely been a joke until recently. Cities often failed to file housing element plans without consequence. State officials rubber-stamped whatever elements were turned in.

The affordability requirements for builder's remedy projects also made these projects unprofitable, or at least unattractive.

Importantly, developers have also generally been loath to piss off city hall by trying to force through one project with a builder's remedy, knowing that it could mean their next one will be blocked.

"In the olden days, what was the special talent a developer had? The special talent was glad-handing. You got to be buddies with the city officials who had discretionary authority over your projects," said University of California, Davis law professor Christopher Elmendorf in an August Twitter Spaces event.

But all this is starting to change.

New state laws have forced cities to prepare more realistic housing elements. The HCD and a new army of YIMBY activists are more willing to call out their traditional housing element dirty tricks—like saying cemeteries and profitable grocery stores will be redeveloped into housing. This means more cities end up having noncompliant housing elements, opening a window for builder's remedy projects.

Rents have also gotten so high in California that developers can still make a tidy profit off a project in which a large percentage of units have to be offered at below-market rates. Lastly, some jurisdictions have garnered enough of an anti-housing reputation that developers see little benefit in trying to stay in their good graces.

Pustilnikov clearly thinks he has nothing to lose by playing nice.

"No one has projects in Redondo. I don't have to worry about Redondo," he says. One gets the impression that the motivations are partly personal. "The reason I chose not to work with the city is primarily out of my past experience trying to work with them, and their propensity to spread half-truths and outright lies," he adds in an email.

There's not a lot of love lost on the other side.

"Leo is a pure speculator and it's laughable that he would buy a piece of property and try to enforce his will onto this community," says Nehrenheim.

A registered Libertarian, Nehrenheim has twice now won elections on a platform of stopping overdevelopment and preventing the "Santa Monica-ization" of the city.

It's proven a popular message in Redondo Beach among an eclectic mix of supporters. His 2021 reelection campaign received donations from the local Sierra Club and the enthusiastic endorsement of the Libertarian Party Mises Caucus.

In an interview with Reason, Nehrenheim likens state laws that override local zoning controls to failed central planning schemes of old and a "Wall Street giveaway."

Redondo Beach, at 11,000 people per square mile, is already one of the densest coastal communities in the state, Nehrenheim notes. Adding more homes on the AES site would worsen already molasses-slow traffic, and cost the city the opportunity for much-needed green space once the power plant is closed, he says.

Nehrenheim also contends that Pustilnikov is just flat wrong about what state law would allow him to build on the AES site without the local community's consent.

This past week, the HCD at last certified Redondo Beach's twice-reworked housing element. With the city once again in the good graces of state housing officials, Nehrenheim argues its is under no obligation to approve a builder's remedy project.

Pustilnikov tells Reason in an email that because he filed his project application before the housing element was certified by the state, the builder's remedy still applies.

Elmendorf says that Pustilnikov is likely right on that point.

A 2019 law, S.B. 330 or the Housing Crisis Act, freezes the rules local officials can apply to a project once its sponsor files a preliminary application. The intent was to stop cities from changing regulations midstream to stop proposed developments that are already in the pipeline.

"There's a decent argument that if you file that preliminary application while the city's [housing element is] out of compliance, then it has to process your project as if it were out of compliance," says Elmendorf.

But, he cautions, a fatal blow to Pustilnikov's project could come from California's regulations on coastal development.

The decades-old California Coastal Act requires seaside localities to adopt plans governing what can be built in coastal zones. The California Coastal Commission has the discretion to reject projects in coastal zones as well. (It's a power the commission has zealously wielded against coastal property owners.)

"The question here is whether the local coastal plan is inconsistent with [Pustilnikov's] project," says Elmendorf. If it is, he says, the coastal regulations win out.

Brandy Forbes, community development director for Redondo Beach, says in an email that the AES site's zoning allows for a park or a power plant, but nothing else, and certainly not housing. Nehrenheim likewise argues that the site's nonresidential zoning makes it off limits for development, even under the Housing Crisis Act.

Pustilnikov says that it's not at all obvious that California's coastal regulations trump his builder's remedy project. He expects he and the city will eventually wind up in court, and that a judge will decide One Redondo's fate.

Any such ruling on the case could have major ramifications outside of Redondo Beach.

California's state government is showing an unprecedented interest in cracking down on what it sees as bad actor NIMBY local governments. The HCD and the California Department of Justice, under Attorney General Rob Bonta, have both created new units dedicated to enforcing state housing laws.

The HCD has been refusing to certify housing elements at an unprecedented rate this cycle. Bonta has also let enforcement letters fly against local jurisdictions trying to skirt recent upzoning bills by, in one instance, declaring the whole town a protected mountain lion sanctuary.

In August, the two departments turned heads when they announced an unprecedented audit of the nation's NIMBY capital, San Francisco, to determine why exactly its leaders keep shooting down new housing.

But it remains to be seen what practical effect this will actually have on enabling new housing production. On paper, there are a couple of sticks Bonta and the HCD can bring down on recalcitrant localities.

Cities out of compliance with state housing law can be stripped of affordable housing and infrastructure funds. But many of the jurisdictions most hostile to new development are small, wealthy suburbs that don't receive much of that money to begin with, and could afford to go without it. And even some YIMBY activists have questioned how politically practical it would be for the state to cut off large cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco from state funding.

State law gives courts the ability to appoint an expert to write a housing element for a city that's out of compliance. But that's a yearslong process and there's no telling how willing a judge would be to actually impose that solution.

That leaves the builder's remedy as the most immediate path for cutting through red tape in California's most anti-development jurisdictions relatively quickly.

It's a solution that has worked in East Coast states, particularly New Jersey. There, developers have made robust use of the builder's remedy to get housing approved. But the Garden State benefits from having pretty clear rules laying out the wheres, whys, and hows of its builder's remedy.

Swirling around California's builder's remedy law, meanwhile, is a fog of unanswered questions about what exactly it allows, how much control local governments retain over projects that make use of it, and how it interacts with other features of state law, including the aforementioned coastal regulations and state-mandated environmental review.

Pustilnikov concedes his Redondo Beach builder's remedy project raises more questions than it answers. But he says his past dealings with the city leave him few options other than rolling the dice on this uncertain solution.

"My experience in the last two years has resulted in me thinking there's really no other way other than letting my kids deal with it," he says. "Considering they're three, eight months, and negative three months, I'd figure I'd take a crack at it before they do."

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (49)