A New Study Suggests That Black Southerners' Access to Firearms Reduced Lynchings

The analysis reinforces the historical case for armed self-defense in response to racist violence.

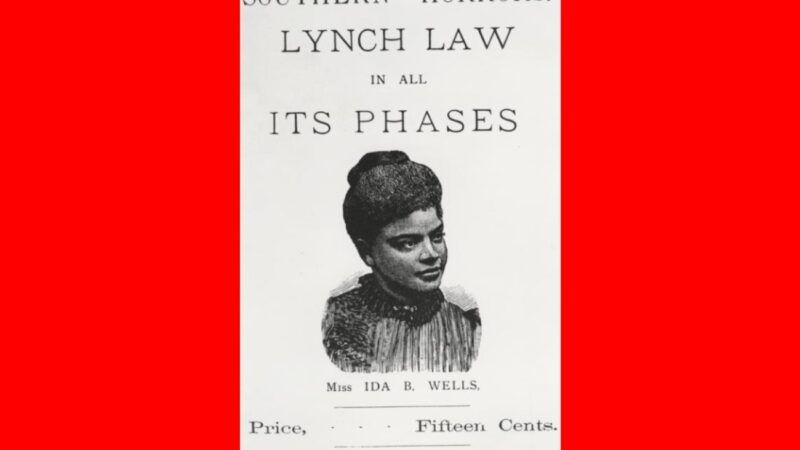

In her 1892 pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, the journalist Ida B. Wells argued that firearms were an essential tool in preventing the deadly white supremacist violence that she chronicled. "Of the many inhuman outrages of this present year, the only case where the proposed lynching did not occur, was where the men armed themselves in Jacksonville, Fla., and Paducah, Ky, and prevented it," she wrote. "The only times an Afro-American who was assaulted got away has been when he had a gun and used it in self-defense."

Wells thought the lesson was clear: "A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give. When the white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs as great risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life. The more the Afro-American yields and cringes and begs, the more he has to do so, the more he is insulted, outraged and lynched."

Many African-American leaders, including Frederick Douglas, W.E.B. Du Bois, T.R.M. Howard, Roy Wilkins, and Martin Luther King Jr., took a similar position, which was supported by voluminous anecdotal evidence. A recent paper by Clemson University economists Michael Makowsky and Patrick Warren reinforces Wells' case for self-help by showing that "rates of Black lynching decreased with greater Black firearm access" during the Jim Crow era.

Makowsky and Warren's data on lynchings come from a 2019 inventory by University of Georgia sociologists E.M. Beck and Stewart Tolnay. "Our sample includes a mean of 2.16 lynching deaths per year, with 41% of state-years experiencing at least one Black lynching death and a maximum of 13 in Georgia in 1922," the economists write. "Lynching deaths per state capita steadily decrease through our window, with upticks in 1919 and 1933."

During this period, Makowsky and Warren note, "Black citizens were subject to state and local governments that were rarely better than indifferent to their safety and, at their worst, actively supportive of terrorist violence targeting them." This was the context in which Wells et al. urged armed self-defense to provide "that protection which the law refuses to give."

As a proxy for firearm access, Makowsky and Warren use the percentage of suicides committed with guns, which they calculate based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau from 1910 to 1950. Since gun control laws in Southern states were used to selectively disarm black residents, the authors also consider the police resources available to enforce those laws. And they take into account fluctuations in retail gun prices, as reflected in Sears-Roebuck catalogs and records from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

"From 1920 to 1940," Makowsky and Warren report, "White firearm access increased

substantially alongside a decline in Black firearm access." Their analysis supports the hypothesis that racially motivated gun control policies had something to do with that.

"Although policies like increased police employment or the enactment of pistol bans were, on their face, race-neutral, these results show that, in practice, they had the consequence of disarming Black residents without having a similar effect on Whites," Makowsky and Warren write. "This differential disarmament could go a long way toward explaining the Black-White firearm access gap that arose in the Jim Crow South."

That racist strategy, the data suggest, had a lethal impact. "In states and years in which Black residents had more access to firearms, there were fewer lynchings," Makowsky and Warren report. "In all three estimation strategy variants, the estimated negative effect of Black firearm access on lynchings is quite large and statistically significant." An increase of one standard deviation in firearm access, for example, is associated with a reduction in lynchings of between 0.8 and 1.4 per year, about half a standard deviation.

"Drawing on historical vital statistics, we show that efforts to disarm Black residents under Jim Crow were successful, as the intra-war period was characterized by a significant relative decline in Black residents' access to firearms," Makowsky and Warren write. "This decline may have had substantial consequences in a world in which the formal institutions of the law would not protect Black citizens' lives and property. Using suicide records as a proxy for firearm access, we find a negative relationship between Black firearm access and the number of recorded lynchings."

Makowsky and Warren think their results "tell a consistent story about how Black firearm access can shift the lynching risk that Black residents of the Jim Crow South faced." That story, "consistent with the historical record, is one in which Blacks residents in fear of lynchings seek out firearms to protect themselves. But in places and times where policy choices and economic circumstances made it difficult, Black residents had less access to firearms, perhaps due to the increased enforcement of disarmament laws targeting Black residents. That reduction in access led to more lynching victims, as Black residents were not able to protect themselves or rely on the institutions of law enforcement to protect them."

Show Comments (87)