The Biggest Obstacle To Building Offshore Wind Farms Is Government

America gets about 42 megawatts of power from offshore wind. Another 18,000 megawatts are currently tied up in permitting battles.

Shortly after taking office last year, President Joe Biden announced an ambitious plan to vastly expand the amount of energy produced by offshore wind farms.

Along the Atlantic coast and in the Gulf of Mexico, the administration identified huge swaths of wind-swept sea that could be put to energy-producing use. Last year, the Department of Energy (DOE) made $3 billion available to upgrade ports so the equipment needed to install offshore wind turbines could be shipped out to sea, and the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act included measures providing tax credits of up to 30 percent for offshore wind projects that are started before 2026. This overall strategy to expand offshore wind production is "a cornerstone of Biden's plan to fight global warming and decarbonize the electricity sector by 2035," Reuters reported last month.

But the biggest impediment to the federal government's attempted development of offshore wind is, it turns out, the federal government.

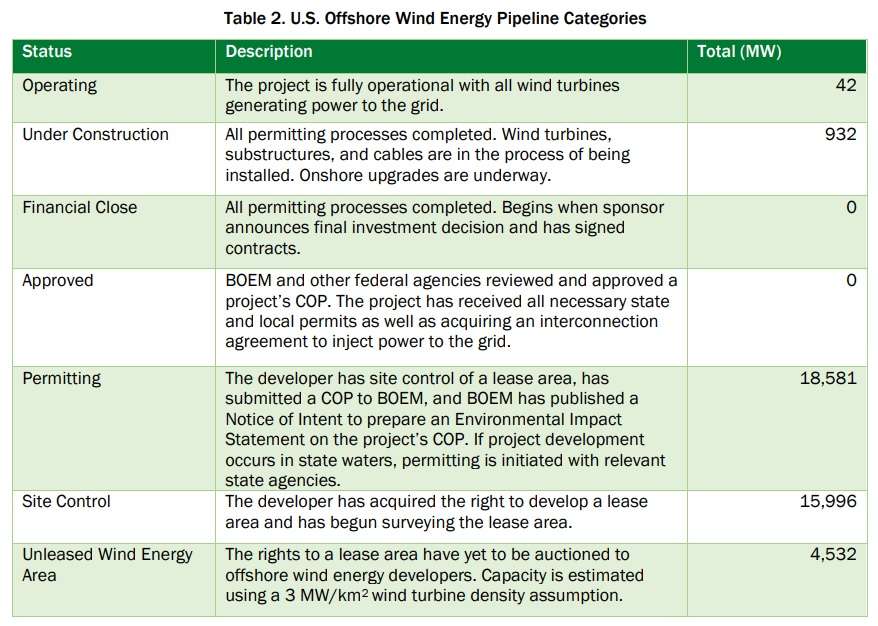

According to DOE data published this month, the U.S. currently has offshore wind projects capable of generating 42 megawatts (MW) of electricity. Offshore wind projects currently under construction will eventually provide another 932 MW of electricity when fully operational. (For comparison's sake, an average-sized nuclear power plant can generate around 1 gigawatt of electricity—equal to 1,000 megawatts.)

But another 18,581 MW of potential offshore wind power are tied up in permitting battles. According to the DOE's data, that means a developer has signed a lease for the designated area but is still trying to complete environmental impact statements required by the federal government and the appropriate state authorities (for projects based in state-controlled waters). As with housing and other types of infrastructure projects, the permitting process provides an opportunity for various parties to slow or even stop construction. Even though the Biden administration has said it intends to speed up the federal permitting process for offshore wind projects, it's questionable whether that is happening. In July, for example, the DOE's Bureau of Ocean Energy Management canceled two potential wind energy developments off the coast of Long Island due to concerns that included "visibility from nearby beaches."

One might wonder about the administration's priorities when its cornerstone energy effort is disrupted by grumpy beachgoers.

I saw the local side of this debate up close during a recent vacation to Long Beach Island in New Jersey, where seemingly every other house is currently sporting a yard sign opposing a new wind project that would be visible from the beach despite being located 15 miles out at sea. A recent article from the island's The SandPaper spells out the regulatory complications: 1,400 pages of documentation, a 45-day public comment period (extended 15 extra days to accommodate "public outcry"), and now a lawsuit that seeks to put the project on hold.

Of course, locals object to new power plants of all varieties and deserve to have their say. Still, the fact that so much of the Biden administration's much-ballyhooed wind projects might be kneecapped long before they become reality ought to generate some skepticism about the usefulness of those big new tax breaks. Regulatory reforms that trim back environmental reviews—and that prevent them from being weaponized by NIMBYs—would be useful not only for getting offshore wind projects built but also for a host of other infrastructure efforts. As Reason's Christian Britschgi has reported, environmental impact statements take 4.5 years on average and run over 650 pages.

It's also worth considering the other tradeoffs involved in these projects. As I wrote last week, a major offshore wind project (one that actually is being built) near Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, will produce only about one-third of the energy that used to be provided by a coal-burning plant that the wind farm is meant to replace—and that's assuming the wind farm operates at full capacity all the time, which of course it won't because sometimes the wind doesn't blow. Even when it does, the electricity produced by offshore wind is more expensive than what is produced by nuclear or gas-powered plants.

Those are the kinds of tradeoffs that would matter even if the Biden administration could snap its fingers and see its stated goal of having America produce 30 gigawatts of electricity from offshore wind by 2030.

But with the regulatory and permitting hurdles facing those wind projects, it's hard to believe we'll get anywhere near that total in the near future.

Show Comments (88)