Incompetent People Are Often Too Incompetent To Realize Just How Incompetent They Are, Says New Study

The less people know about a scientific issue, the more confident they are that they are right.

"Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge," wrote Charles Darwin in The Descent of Man (1871). Experimental findings reported in 1999 by social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger bolstered Darwin's insight. They tested people on their knowledge of grammar and logic and found that many of the people who did badly on the tests rated their performance as being well above average. On the other hand, those who did well tended to underestimate how well they had done.

The now eponymous Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people "wrongly overestimate their knowledge or ability in a specific area. This tends to occur because a lack of self-awareness prevents them from accurately assessing their own skills." In other words, incompetent people are often too incompetent to realize just how incompetent they are. (It should be noted, however, that some now suggest that the Dunning-Kruger effect is not a real phenomenon but arises from how the researchers parsed their data.)

In any case, most of us do suffer from various forms of cognitive overconfidence such as the "illusion of explanatory depth." We actually think we know how many of the mechanisms and processes we interact with every day actually operate. But when we are asked to draw or write down how a zipper, a bicycle, or a flush toilet works, we find that we don't know as much as we initially thought we did. And let's not get started on the massive problem of confirmation bias when it comes to politically salient issues.

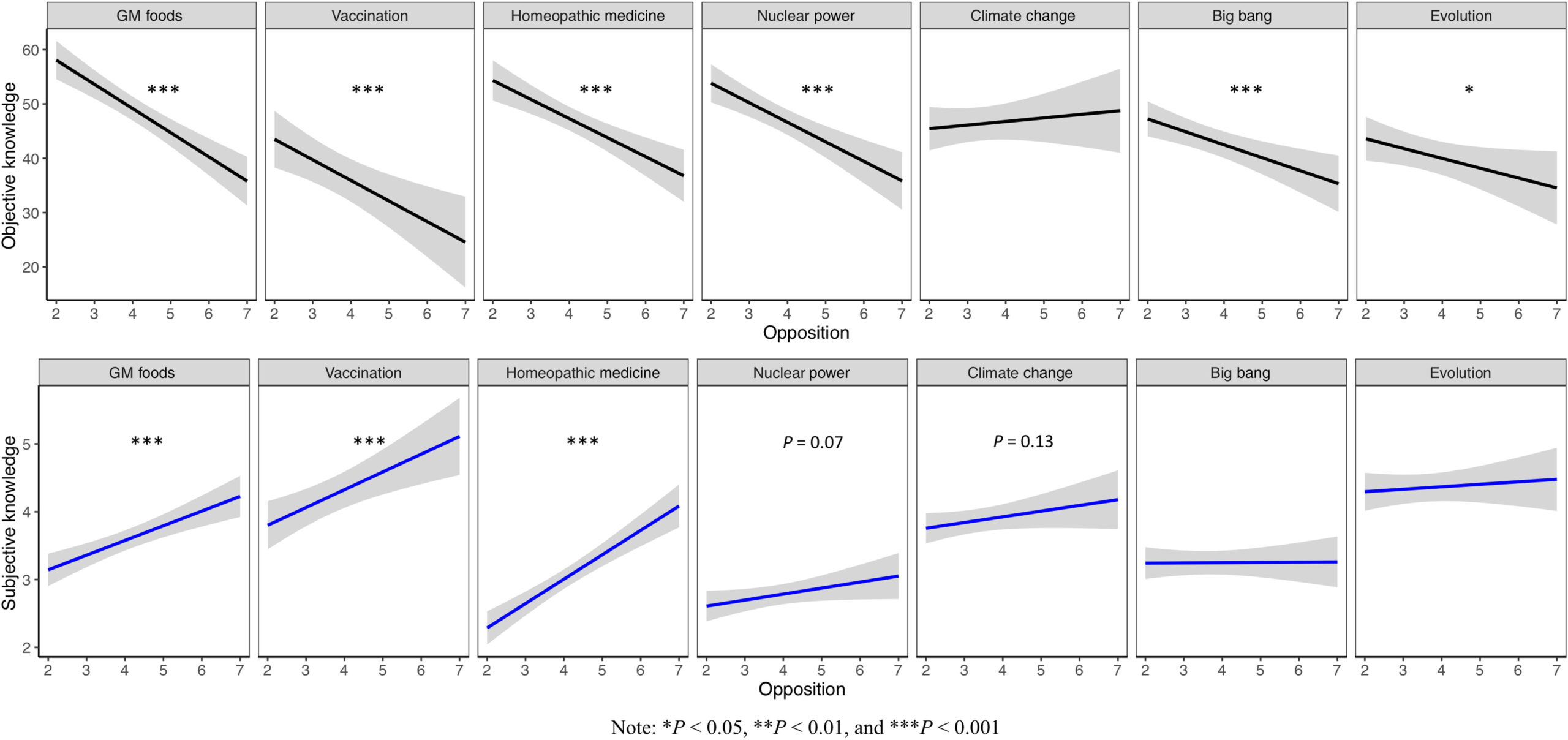

Now, a new study in Science Advances adds to these findings and reports that "knowledge overconfidence is associated with anti-consensus views on controversial scientific issues." In the study, the researchers first asked 3,200 participants through online surveys how much they think they know (subjective knowledge) using a 7-point scale about each of seven scientific topics ranging from "vague understanding" to "thorough understanding." To prime participants, the researchers provide a complex explanation of how a crossbow is constructed and works (level 7 knowledge) compared to the case where a person can identify a crossbow and know that it shoots arrows (level 1 knowledge). Then each participant was randomly assigned to answer a question about their degree of acceptance of one of the seven different issues that enjoy substantial scientific consensus.

The issues probed by the researchers were "the safety of GM foods, the validity of anthropogenic climate change, the benefits of vaccination outweighing its risks, the validity of evolution as an explanation of human origins, the validity of the Big Bang theory as an explanation for the origin of the universe, the lack of efficacy of homeopathic medicine, and the importance of nuclear power as an energy source." For each issue, participants were asked to indicate their level of opposition ranging from not at all (level 1) to extreme (level 7).

To figure out how much participants might know about scientific findings in general, researchers also tested them on a 7-point objective-knowledge scale ranging from definitely false, not sure, to definitely true for 34 different purportedly factual claims about the world. The researchers divvied up the 34 statements into clusters relevant to the topics of evolution, the Big Bang, nuclear power, genetically modified foods, vaccination and homeopathy, and climate change. Among the statements participants were asked to answer true or false were assertions like the center of the earth is very hot; all radioactivity is man-made; ordinary tomatoes do not have genes, whereas genetically modified tomatoes do; the earliest humans lived at the same time as the dinosaurs; and nitrogen makes up most of the earth's atmosphere.

The researchers also asked participants about their political and religious views.

The researchers then compared the strength of the participants' claims to subjective knowledge, that is, how sure they were that the scientific consensus of the seven topics was right or wrong, with the depth of their objective knowledge as revealed by their answers to the 34 purportedly factual claims.

In general, the researchers found "that the people who disagree most with the scientific consensus know less about the relevant issues, but they think they know more." Interestingly, as the above chart shows, study participants tended to have a bit less confidence in their views with respect to the highly polarized issue of climate change and the origins of the universe and species.

The researchers do acknowledge that "conforming to the consensus is not always recommended." They cite the opposition of Plato and Galileo Galilei to philosophical and scientific consensuses of their eras as examples. They might well have noted the pernicious consensus in favor of eugenics that prevailed in the early 20th century.

Nevertheless, the researchers conclude that "if opposition to the consensus is driven by an illusion of understanding and if that opposition leads to actions that are dangerous to those who do not share in the illusion, then it is incumbent on society to try to change minds in favor of the scientific consensus." Dangerous actions like trying to ban more productive and environmentally friendly crop varieties, refusing vaccination against dangerous infectious diseases, or rejecting a safe technology for generating electric power.

Show Comments (504)