SCOTUS Rejects 'Interest-Balancing' Tests That Treated the Second Amendment As a 'Constitutional Orphan'

The ruling against New York's carry permit policy is a rebuke to courts that routinely rubber-stamp gun restrictions.

When it ruled against New York's restrictions on gun possession outside the home yesterday, the Supreme Court delivered a rebuke to government officials who presume to decide which individuals may exercise a constitutional right. The decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen is also a rebuke to lower federal courts that for years have been rubber-stamping gun control laws based on a "two-step" analysis that frequently amounts to approving restrictions as long as the government can articulate reasons for them.

In the landmark 2008 case District of Columbia v. Heller, the Court recognized that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to armed self-defense, including the right to keep handguns at home for that purpose. Two years later in McDonald v. Chicago, the Court extended that logic to state and local laws that prohibit people from keeping handguns for self-defense. Both decisions relied heavily on historical evidence that illuminated the Second Amendment's meaning and scope, including legal commentary, judicial decisions, and the types of gun laws that were enacted in the 18th and 19th centuries.

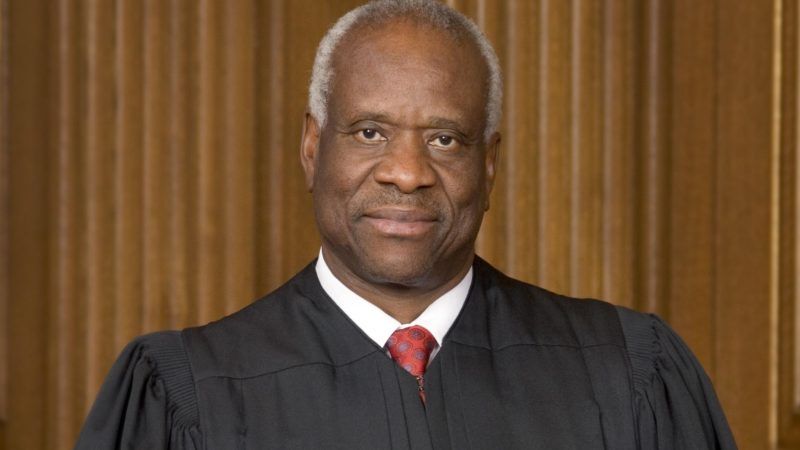

"In the years since, the Courts of Appeals have coalesced around a 'two-step' framework for analyzing Second Amendment challenges that combines history with means-end scrutiny," Justice Clarence Thomas notes in the Bruen majority opinion. "Today, we decline to adopt that two-part approach."

That is not surprising, because that approach has proven highly deferential to the government. In step one, a court asks whether a challenged law regulates conduct that falls within the scope of the Second Amendment as it was originally understood. If the court deems the historical evidence on that score inconclusive, Thomas notes, it proceeds to step two, asking "how close the law comes to the core of the Second Amendment right and the severity of the law's burden on that right."

Appeals courts generally have identified that "core" as self-defense in the home, the right at issue in Heller and McDonald. If that right is implicated, they apply "strict scrutiny," which requires that a law be "narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling governmental interest." Otherwise, they apply intermediate scrutiny, which requires that a restriction be "substantially related to the achievement of an important governmental interest."

In practice, as 9th Circuit Judge Lawrence VanDyke pointed out in January, "intermediate scrutiny" often looks a lot like a "rational basis" test, which requires only a "rational connection" between a law and "a legitimate state interest." If the state offers a justification that is not patently nonsensical, that usually suffices.

The 9th Circuit has epitomized that sort of casual disregard for the Second Amendment in decisions upholding policies like California's 10-round magazine limit, San Diego's "good cause" requirement for carrying concealed firearms (which is essentially the same as the New York law that the Supreme Court rejected yesterday), and Hawaii's similarly restrictive rules for openly carrying firearms. "Our circuit has ruled on dozens of Second Amendment cases, and without fail has ultimately blessed every gun regulation challenged," VanDyke complained. "Our circuit can uphold any and every gun regulation, because our current Second Amendment framework is exceptionally malleable and essentially equates to rational basis review."

VanDyke made that observation in a case involving pandemic-inspired shutdowns of gun stores, which he and another judge on a three-member panel concluded were inconsistent with the Second Amendment. He went on to demonstrate the malleability of the 9th Circuit's framework with a 12-page satirical opinion that he suggested his colleagues on the appeals court could use when they overturned the panel's decision, which he thought was inevitable. The mock opinion began with a gesture toward historical evidence, which it found unilluminating, then proceeded to minimize the burden imposed by banning gun sales, such that the government could easily prevail by doing little more than avowing its good intentions.

Enough of that, the Supreme Court says in Bruen. "In keeping with Heller," Thomas writes, "we hold that when the Second Amendment's plain text covers an individual's conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. To justify its regulation, the government may not simply posit that the regulation promotes an important interest. Rather, the government must demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with this Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only if a firearm regulation is consistent with this Nation's historical tradition may a court conclude that the individual's conduct falls outside the Second Amendment's 'unqualified command.'"

Following that approach, Thomas scrutinizes the historical examples that New York offered to show that its policy, which allowed people to carry handguns in public only if they satisfied a local official that they had "proper cause" to do so, was consistent with regulations that were widely accepted when the Second Amendment and the 14th Amendment (through which the Bill of Rights applies to the states) were ratified. Finding that evidence unpersuasive, Thomas concludes that "the State's licensing regime violates the Constitution" by requiring New Yorkers to demonstrate "a special need" before they can exercise the right to bear arms.

Such a demand, Thomas observes, would never be tolerated in other constitutional contexts. "We know of no other constitutional right that an individual may exercise only after demonstrating to government officers some special need," he writes. "That is not how the First Amendment works when it comes to unpopular speech or the free exercise of religion. It is not how the Sixth Amendment works when it comes to a defendant's right to confront the witnesses against him. And it is not how the Second Amendment works when it comes to public carry for self-defense."

When confronted by policies like New York's, Thomas says, courts should not "balance" the government's asserted interest against the rights guaranteed by the Second Amendment. "Heller relied on text and history," he writes. "It did not invoke any means-end test such as strict or intermediate scrutiny."

In fact, Thomas says, Heller and McDonald "expressly rejected" the application of "any judge-empowering 'interest-balancing inquiry' that 'asks whether the statute burdens a protected interest in a way or to an extent that is out of proportion to the statute's salutary effects upon other important governmental interests.'" Heller noted that the Second Amendment "is the very product of an interest-balancing by the people," and it "surely elevates above all other interests the right of law-abiding, responsible citizens to use arms" for self-defense.

Thomas, who has complained for years that courts were treating the Second Amendment as a "second-class right" and "a constitutional orphan," thinks it should have been clear from Heller that judges are not supposed to take the deferential approach that VanDyke satirized. Evidently, it was not. But now courts no longer have any excuse for treating the Second Amendment as less important than the rest of the Bill of Rights.

Show Comments (24)