The Fuzzy Moral Line Between Drinkers and Bartenders

Were liquor suppliers across the world guilty of outrageous abuses that explain the prohibitionist response?

Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition, by Mark Lawrence Schrad, Oxford University Press, 725 pages, $34.95

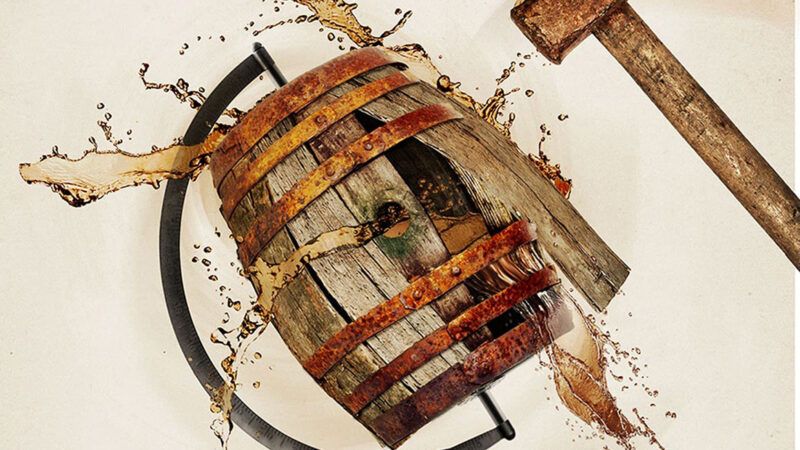

Mark Lawrence Schrad thinks Carrie Nation, the hatchet-wielding vigilante who rampaged through saloons at the beginning of the 20th century, gets a bum rap. While Nation was "easy to mock as a Bible-thumping 'crank,' 'a freak,' 'a lunatic,' or a 'puritanical killjoy,'" Schrad says, she was actually a courageous and kindly woman devoted to "justice, love, and benevolence." Her enemy "was not the drink or the drinker, but 'the man who sells,'" Schrad, a Villanova political scientist, writes in Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition. "This is important."

I'm not sure that distinction, which underpins Schrad's broader effort to redeem the reputation of alcohol prohibitionists, is as important as he thinks. I'm not even sure it makes sense. Without drinkers, after all, there would be no brewers, vintners, distillers, liquor merchants, or tavern keepers. In Schrad's telling, the customer is not king; he is barely a serf.

Schrad's defense of prohibition depends on the notion that people have no real control over whether or how much they drink. Schrad, who confesses to a fondness for Manhattans but nevertheless seems to have avoided a disastrous descent into alcoholism, surely knows that is not true. Yet without that fiction, his distinction between "the drinker" and "the man who sells" dissolves like the sugar in a well-mixed old fashioned.

Schrad's exhaustive study, the product of prodigious and groundbreaking research, nevertheless complicates the conventional understanding of alcohol prohibition, which sees it as a distinctly American and reactionary phenomenon. According to this view, Schrad says, the movement to ban alcohol was "the last-gasp backlash of conservative, rural, native-born Protestants against the rising tide of urbanization, immigration and multiculturalism in turn-of-the-century America." To the contrary, he shows, the movement spanned the globe, often pitting "subaltern" groups against elites and native leaders against colonizers. "Prohibitionism," Schrad writes, "wasn't moralizing 'thou shalt nots,' but a progressive shield for marginalized, suffering, and oppressed peoples to defend themselves from further exploitation."

Even as he strives to correct caricatures of prohibitionists, Schrad indulges in sweeping stereotypes of liquor vendors, whom he reflexively describes as "unscrupulous" or "predatory." The liquor joints of the time, he emphasizes, were nothing like Sam Malone's "cozy, respectable" bar on Cheers, "where everybody knows your name" and the proprietor is "like a therapist or best friend" who makes sure his customers get home safely when they overimbibe.

The man in charge of the village kabak in 19th century Russia, in contrast, was a "shyster" who "became the primary interface between the peasant and the predatory state," which had a monopoly on vodka production. "By oath," Schrad writes, "he could never refuse even a habitual drunkard, lest the tsar's revenue be diminished." He would gladly continue serving customers until their pockets were empty, forcing them to exchange their clothes for more before ejecting them to die naked in the cold. The Russian state was so dependent on alcohol revenue that in 1859 it brutally suppressed a "temperance revolt" in Spassk; elsewhere, soldiers literally forced vodka down the throats of recalcitrant peasants.

While these are extreme examples, Schrad's general thesis is that liquor suppliers across the world were guilty of outrageous abuses that explain the prohibitionist response. No doubt that was true in many cases. But Schrad's unremittingly negative portrait of the industry makes you wonder: Was there no such thing as an honest liquor merchant or a happy customer? Did saloons offer nothing but misery and corruption?

Schrad is so intent on painting alcohol sellers as villains that he is driven to contradiction. He faults them for selling high-proof products, which he views as especially addictive. But he also faults them for watering down their drinks, which by his logic should have made their wares less dangerous. He criticizes them for low prices, which encouraged overconsumption, but also for high prices, which drove heavy drinkers further into poverty. And government liquor monopolies are alternately bad or good, depending on who is in charge: avaricious autocrats in Russia or enlightened regulators in Sweden.

The medical and social harms of alcoholism that Schrad describes are beyond dispute. The question is whether those costs justify criminalizing peaceful transactions between consenting adults. Here is where Schrad's line between drinkers and "the liquor machine" becomes hazy.

The relevance of the choices made by individual drinkers is hard to miss in Schrad's account of protests by Mohandas Gandhi's followers at Indian liquor stores, which his campaign of "nonviolent noncooperation" targeted because they generated revenue for the British Raj. "Not only would nationalists boycott liquor themselves, they would actively scare away would-be drinkers from the government stores," Schrad explains. "While not preventing entry by force, one of the (usually) seven or eight picketers would verbally harass would-be customers, sometimes hurling 'very filthy language.'" If the customers nevertheless completed their purchases, they faced even worse abuse on their way out.

Gandhi was appalled when these protests descended into murderous violence. But even the initial tactics make it clear that the anti-liquor activists were angry at drinkers as well as the businesses that supplied them. And Gandhi's endorsement of legal prohibition, which necessarily involves the use of force, is hard to reconcile with a commitment to peace and tolerance.

Schrad nevertheless insists that prohibitionists did not oppose "the individual's right to drink." Rather, they opposed "profit-making from trafficking in addictive substances." Let us consider that distinction in the U.S. context.

Unlike our current drug laws, the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act did not prohibit the mere possession or consumption of the substance they targeted. But they did ban the "manufacture" as well as the "sale" and "transportation" of "intoxicating liquors." That ruled out home brewing, wine making, and distilling, except for religious or medicinal purposes. So even drinkers who had the supplies, equipment, and know-how to make their own alcoholic beverages faced punishment if they got caught doing it. That point aside, the prohibition of commercial production and distribution obviously had a big, intentional impact on Americans' ability to legally exercise "the individual's right to drink."

The black market created by that policy did not ameliorate the iffy quality and official corruption that Schrad ties to the legal alcohol industry. It made those problems worse, while also fostering violence, boosting organized crime, and undermining civil liberties. Nor did Prohibition unambiguously deter excessive drinking: It pushed suppliers toward more potent products that were easier to smuggle, and it drove consumption underground, weakening the social forces that encourage moderation. Such effects persuaded many Americans who initially supported Prohibition that the "noble experiment" had failed.

Despite Schrad's avowed empathy for the common man, he has little patience with the indignant drinker who thinks his choice of recreation is no one's business but his own. Schrad takes it for granted that political leaders should be free to choose whatever policies they think will promote the public welfare.

As Schrad notes, the British philosopher John Stuart Mill generally championed the same "great reforms" as illustrious prohibitionists such as Frederick Douglass, including abolition, universal suffrage, and equal rights for women. But Mill parted company with Douglass et al. when it came to restricting alcoholic beverages. "Prohibition of their sale is in fact, as it is intended to be, prohibition of their use," Mill wrote. "The infringement complained of is not on the liberty of the seller, but on that of the buyer and consumer."

Schrad rejects Mill's "right-to-drink argument" because it "effectively exonerated the liquor trafficker's predations; the man who sells simply disappears from the equation." In Schrad's formulation, by contrast, the drinker disappears from the equation, since seemingly voluntary transactions are redefined as "predations."

If your concept of liberty includes the right to acquire and exchange property, of course, you might have a different objection to Mill's take: Why not defend "the liberty of the seller," as long as he is honest and the buyer is willing? Schrad draws a distinction between "political rights," which he says are based on "Enlightenment principles," and "economic liberties," which evidently are not. But this line is at least as fuzzy as the one between the drinker and "the man who sells."

Schrad's political rights include religious liberty and freedom of the press. It is hard to exercise those rights without economic liberties such as the right to buy land for a church or the right to buy tools of communication. And if people don't have a right to the fruits of their labor, meaning their livelihoods depend on the state's discretion or largesse, all their other rights are insecure.

Schrad calls prohibition "part of a long-term people's movement to strengthen international norms in defense of human rights, human dignity, and human equality, against traditional autocratic exploitation." But if human rights don't include economic liberties, traditional autocratic exploitation can easily be replaced by equally oppressive forms of tyranny.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Testing testing

All I had to read was: “peoples movement” to know this guy is an asshole.

Guy sounds like a flaming asshole with a bunch of letters after his name who has gotten good at rooking idiots with flowery language.

The guy is a complete fucking retard. The folks who ignore the 10% or whatever who really are effectively incapable of using higher order brain function when it comes to the question of alcohol consumption are missing something. And, more generally, this group is enhanced quite a bit from the ranks of people who realize it's a problem but "Prohibition" isn't the answer.

But then to go all the way over to the other side? Treat *every* fellow person as if they're a pathetic puppet? God damn, dude. Fuck off.

I remain amazed that no bartender ever saw that crazy bitch come through the doors of his saloon, and just dumped a chestful of #00 into her.

"I've come to vandalize your perfectly legal business, destroy it, and leave you destitute because I don't like what you sell."

"Nope." *boom*

You know who else was a priggish teetotaler in love with his own voice?

Cromwell?

William Jennings Bryan? Herbert Hoover? Billy Sunday?

“The man in charge of the village kabak in 19th century Russia, in contrast, was a "shyster" who "became the primary interface between the peasant and the predatory state," which had a monopoly on vodka production. "By oath," Schrad writes, "he could never refuse even a habitual drunkard, lest the tsar's revenue be diminished."”

Sounds to me that the evildoer here is the state, running a monopoly simply to squeeze money out of peasants. But a statist would never admit that.

It does take a particularly large blind spot to leave out the part where this notionally predator shyster (isn't that typically an anti-Semitic slur?) was likely to *also* end up being forced to chug vodka he didn't want if he didn't sell enough of it by the soldiers with *guns*.

I mean, given that situation, it's hard to imagine how anyone could possibly place blame anywhere except on the very notion of retailing alcohol, and therefore that same violent state should be used to suppress its sale instead of mandate it. I'm sure that'll solve all the problems.

Alcohol was banned in Russia, and soon the Czar and family were murdered and the economy a wreck. It was later banned in America and soon the Prohibition party was a wreck, along with its Republican brood host and the economy. Pattern?

" In Schrad's telling, the customer is not king; he is barely a serf."

This is a common progressive whine.

They are either too ideologically stupid to recognize "democratic" choice in a free market, or too stupidly ideological to allow others to exercise their choices. I once had an argument with an eagerly dumb progressive college student about this, focused on cars. She claimed that big, evil corporations prevented people from buying the kind of cars they want. I pointed out that vehicle choices, including fuel type, had never been better. She could not accept that because, I suspect, she had gone all in on the victimized citizen narrative. (Or maybe she really wished to make those choices for other people.)

I hope you didn't spend too long arguing with a telephone post like that.

Mycotoxins Testing

Mycotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by fungi or molds in grain in the field or during storage. https://www.lifeasible.com/custom-solutions/food-and-feed/food-testing/residues-and-contaminants-testing/mycotoxins-testing/

Typical "progress/Woke" fascism.

"We, the woke" know what is best for you the poor.

Fuck off.

Cigarettes. Fast food (or unhealthy food of any type). Alcohol. As stated above, gas-guzzling cars.

In progressive fever dreams, "evil corporations" or capitalism itself, cause bad things. They never look around and see that people, and their individual choices, cause bad things.

The sky is truly red and the grass blue in their world.

That's right up there with "the parties switched sides", "the Nazis weren't socialists", "Southern strategy", and "Democrats helped gay liberation". It's a fiction created by progressives and now maintained by everybody.

Prohibition peaked concurrently with Marxism and the rise of the Progressives. That is not a coincidence.

In both the US and the UK, prohibition was largely a middle-class (in the US, largely middle-class protestant) movement, directed against the poor, with definite proto-feminist overtones. I knew a woman who grew up on Flatbush Ave. in Brooklyn in a largely Italian neighborhood in the 1960s. Every Friday night all the Italian men would get drunk, and every Saturday morning all the Italian women would have black eyes. Makes you think, doesn't it?

Ashrad and ilk are tools of the Glucose Trust making corn sugar from crops in wet mills. Bloated during the War between dry Czarist Russia and the narco-States of Austria-Hungary, GB, Grance and Germany desperate for revenue lost from Chinese prohibitionism, pharma went to war. Glucose and yeast cartels bought politicians to ban distillers and brewers. Households then turned to corn sugar, yeast and malt extracts for ethanol, but so did policeman-racketeers. To break the surprising proliferation of moonshine entrepreneurs, the economy had to be wrecked.