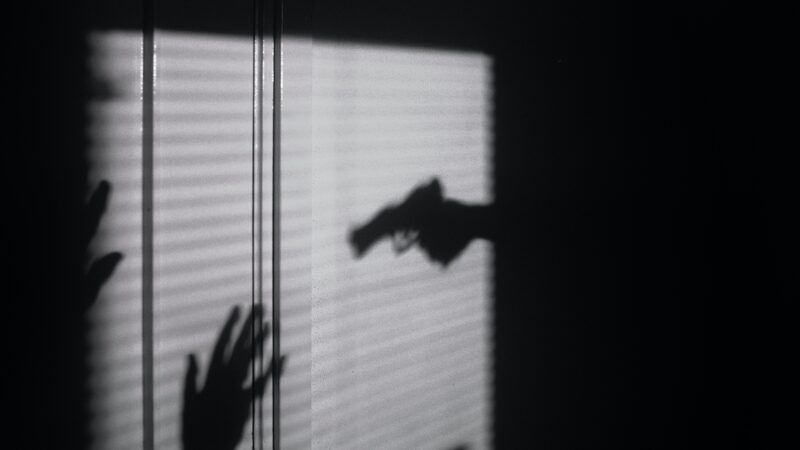

An Off-Duty Cop Murdered His Ex-Wife. The California Highway Patrol Ignored the Red Flags.

When cops don't police their own, the results can be deadly.

When law-enforcement officials believe that someone has committed a crime, they often go to great lengths—and can be quite creative—in coming up with charges to file. Criminal codes are voluminous, and it's common for prosecutors to pile up one charge after another as a way to keep someone potentially dangerous off the streets.

When the accused is a police officer, however, agencies typically find their hands tied. "Nothing to see here," they say, "so let's move along." Their eagerness to protect their own colleagues from accountability can have deadly consequences. A recent lawsuit by the victim of a California Highway Patrol officer's off-duty shooting brings the problem into view.

The case centers on Brad Wheat, a CHP lieutenant who operated out of the agency's office in Amador County. On Aug. 3, 2018, Wheat took his CHP-issued service weapon and hollow-point ammunition to confront Philip "Trae" Debeaubien, the boyfriend of Wheat's estranged wife, Mary. As he later confessed to a fellow officer, Wheat planned more than a verbal confrontation.

"I just learned this evening that Brad confided in an officer…tonight that he drove to a location where he thought his wife and her lover were last night to murder the lover and then commit suicide," an officer explained in an email, as The Sacramento Bee reported. Fortunately, Debeaubien had left the house by the time that Wheat arrived.

Initially, Wheat's colleagues convinced him to surrender his CHP firearm and other weapons and they reported it to superiors. Instead of treating this matter with the seriousness it deserved, or showing concern for the dangers that Debeaubien and Mary Wheat faced, CHP officials acted as if it were a case of an officer who had a rough day.

They essentially did nothing. "Faced with a confessed homicidal employee, the CHP conducted no criminal investigation of its own, notified no allied law enforcement agency or prosecutor's office, and initiated no administrative process," according to a pleading filed by Debeaubien in federal district court. "Nor did the CHP notify [the] plaintiff that he was the target of a murder-suicide plan that failed only because of a timely escape."

You read that right—the agency seemed so uninterested in the safety of two potential murder victims that it didn't even inform them about the planned attack. It sent Wheat to a therapist, who reportedly said he needed a good night's sleep. It sent him on vacation for two weeks, let him return to work, and returned his firearm and ammunition—something CHP said he needed for his job.

You can probably guess what happened next. Two weeks later, Wheat took the same weapon and ammo and this time found his ex-wife and her boyfriend. He shot Debeaubien in the shoulder, the two struggled and Wheat—a trained CHP officer, after all—retrieved his dislodged weapon, shot to death his ex-wife, and then killed himself.

Now CHP says it has no responsibility for this tragic event and that its decisions did not endanger the plaintiff's life. This much seems clear from court filings and depositions: CHP's response centered on what it thought best for its own officer. Any concern about the dangers faced by those outside the agency seemed incidental, at best.

CHP officials considered in one email some protective action but chose not to arrest Wheat on attempted murder charges, nor place him on psychiatric hold for evaluation, nor seek protective orders for Debeaubien or Mary Wheat. Yet police agencies typically embrace those types of approaches when the accused is a mere "civilian."

CHP officials expressed concern about protecting Wheat's career, and one worried that Mary Wheat or Debeaubien might file a complaint. Even when a colleague asked Wheat to relinquish his firearm, he did so as a friend—not as CHP protocol. Again, CHP treated Brad Wheat as the focus of sympathy, not as the potential perpetrator of domestic violence. (Perhaps CHP needs to get with the times and embrace programs that teach officers to react proactively to these situations.)

The case also raises issues about qualified immunity—the legal doctrine that protects government officials from liability even when they violate the public's constitutional rights. CHP offers this doctrine as a "get out of jail free" defense. The public has no right to sue public employees for failing to protect them, Debeaubien's attorneys respond, but the courts carved out an exemption when they affirmatively put people in danger.

That's what happened here. "Giving a gun to a then-weaponless man who 'had driven to a location where he thought his wife and her lover were to murder the lover and then commit suicide,'…creates an actual and particularized danger of his using the gun to attempt murder a second time," the filing notes. That would seem obvious to anyone, except perhaps a police agency more interested in protecting itself than the public.

This column was first published in The Orange County Register.

Show Comments (22)