Zoning Officials Stop Church From Opening 40-Bed Shelter in Sub-Zero Temperatures

Gloversville's Free Methodist Church has 40 beds ready and waiting at its downtown shelter. City officials say the zoning code doesn't allow people to sleep in them.

Temperatures in Gloversville, New York, are expected to fall to -4 degrees tonight. That's bad news for the roughly 80 homeless people who live in the upstate community, and who have few options for escaping the dangerously frigid weather.

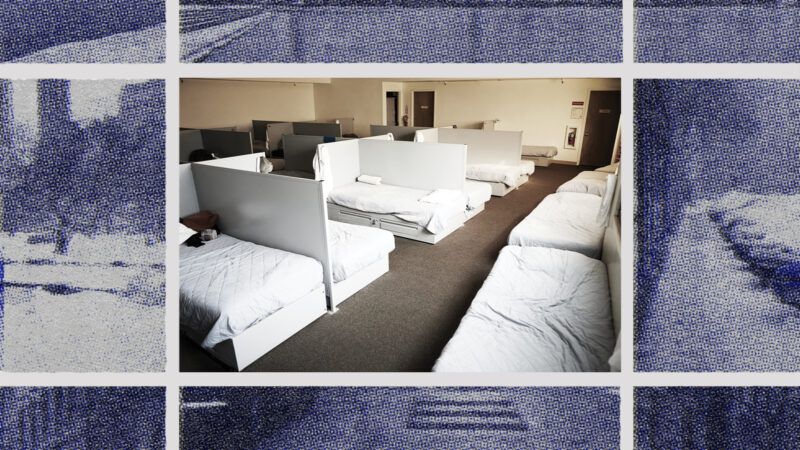

About half of those people could be housed on the second floor of a building owned by the city's Free Methodist Church, where 40 empty beds sit ready to welcome people in from the cold.

Stopping that from happening are Gloversville's zoning officials, who say that the commercial zoning of the church's property and its downtown location prohibit it from hosting a cold weather shelter. Those empty beds will have to stay that way.

"The situation is dire up here and the city just refuses to let us open," says Richard Wilkinson, the pastor of Gloversville's Free Methodist Church. "It's heartbreaking knowing there's people out there."

Wilkinson's efforts to open a cold weather shelter date back to late 2019. At the time, Fulton County, which contains Gloversville, had no homeless shelter. Opening one would help it meet its obligation under a 2016 "code blue" executive order issued by then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo to have a plan to shelter the homeless when temperatures dropped below freezing.

The Free Methodist Church's downtown building on Bleecker Street seemed like the perfect location for it, says Wilkinson. The ground floor of the former YWCA facility already served as a food pantry. The second floor had more than enough space to accommodate sleeping quarters. The building also had bathroom facilities and a commercial kitchen, so people staying there could also get a hot shower and hot meal.

Better yet, the shelter would be located in the city's downtown where most of the homeless were already congregated.

"All the homeless are down here in the center of the city," Wilkinson tells Reason. "There's a lot of services. In Gloversville, they can get a meal five to six days a week. There's a lot benefit to having it down here."

Beginning in November 2019, Wilkinson and other churches and community organizations started working to turn their idea into a reality. The community and city government proved quite receptive to the effort at first.

It took only a few days for them to raise the $60,000 they needed to get their Center for Hope shelter up and running. Local businesses generously donated linens and pillows to the effort. The mayor and then-chief of police were in active conversations about the new shelter. An initial city building inspection turned up only minor issues that were easily remedied, says Wilkinson.

But this positive momentum was derailed in February 2020 when, on the same day the shelter was set to have its final building inspection, the city informed Wilkinson that there was a problem.

He was told that his property's commercial zoning and location in a "Downtown Urban Core Form-Based Overlay District" meant that a code blue shelter might not be allowed and he would have to go before the city's planning board in order to get permission to open.

Community outcry saw the city issue the church a temporary permit to operate a code blue shelter that year. But legalizing it long term required the Free Methodist Church to go through a monthslong planning process and come up with a site plan and architectural drawings.

At a September 2020 planning board meeting, Wilkinson and his lawyer made the case for his shelter in person. They said that the shelter's temporary options that year had been a success. They'd managed to fill 27 bunks that winter, and get a number of the people who came through their doors into mental health or drug addiction treatment.

The biggest issue that occurred was when one of the shelter residents urinated in front of a neighboring business.

They noted that because the city's zoning code was silent on whether code blue shelters were an allowable use in the property's commercial zoning, while similar things like rooming houses and hotels were allowed, the shelter should be allowed to open.

None of this proved convincing to the planning board. In October, it sent Wilkinson a letter saying that his property's zoning did not permit the operation of a code blue shelter.

In response, Wilkinson took his case to the city's zoning board of appeals, where he argued that the planning board was misinterpreting the zoning code and that his church's shelter should be allowed to open.

That proved fruitless as well. In a letter dated January 22, 2021, the zoning board of appeals affirmed earlier decisions by the city that a code blue shelter was not an allowable use in commercial zones, and therefore the Bleecker Street shelter would have to either obtain a zoning variance or close.

These administrative rejections of Wilkinson's code blue shelter were mirrored by the Gloversville City Council.

On New Year's Day 2021, the council passed an amendment to the city's zoning code that permitted code blue shelters in commercial zones, but also expressly prohibited them in the city's downtown "form-based overlay zone" where the Bleecker Street shelter is located.

Wilkinson says that the city did provide some funding in 2021 to open a compromise shelter farther from the downtown, but that proved unworkable. The new location, he said, had only eight beds and one bathroom. The sinks frequently broke and winter winds blew in a window.

Left with no other options, the Free Methodist Church sued Gloversville's zoning board in February 2021. Its lawsuit is ongoing.

This afternoon, local ABC affiliate WTEN reported that the city government inked papers this morning to lease a shuttered VFW hall near the city's downtown that will serve as a temporary 20-bed code blue shelter.

"We knew that the weather was cold out there. We wanted to provide this service to the community, especially to people in desperate need of shelter," Mayor Vincent DeSantis told WTEN this afternoon.

In a press release, the Center of Hope's advisory board said it was "grateful" to city leaders "for not only acknowledging the homeless population but putting together a

temporary solution."

Wilkinson tells Reason that he has had no involvement with the city's efforts, and therefore doesn't know what kind of facilities or services will be on offer at the new temporary shelter. But he says he's glad that the city is getting people out of the cold.

Nevertheless, he says this hasn't changed any of his plans to open a shelter at the Bleecker Street property and that his church's lawsuit will continue.

With regard to that shelter, Wilkinson told Reason yesterday that the city has done everything in its power to throw up roadblocks to his church's charitable efforts and that people are suffering as a consequence.

"What it comes down to is it's freezing. All it is is a line in the city code that is keeping people from sleeping in the warmth," says Wilkinson. "It's ridiculous to me that anybody would allow people to sleep in the cold when there's a place where they could come inside and get warm."

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (55)