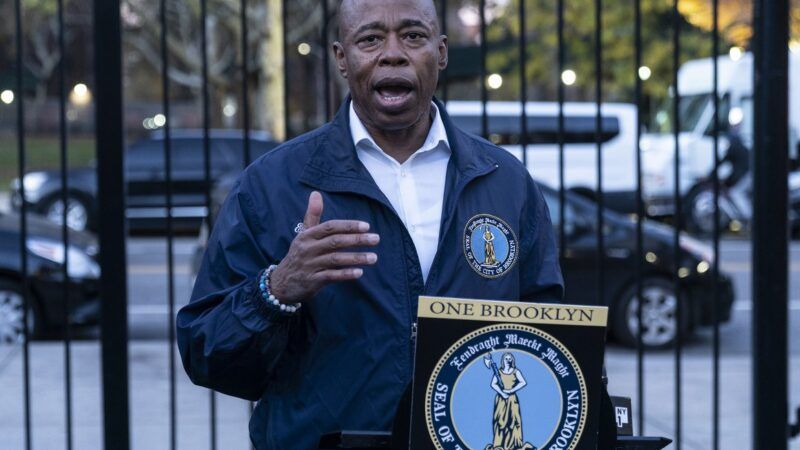

Incoming New York Mayor Makes Vague Case for the 'Proper' Kind of Stop-and-Frisk

Eric Adams thinks he can give the police more power to hunt for guns without making innocent minority men the inevitable target.

Writing in the Daily News, New York Mayor-elect Eric Adams is vaguely promising a kinder, gentler "stop and frisk" policing.

On the campaign trail, Adams had said that he didn't fully oppose the concept of "stop and frisk"—the police practice stopping people with very little suspicion to make sure they aren't carrying guns or drugs—but that he believed the New York Police Department (NYPD) had abused its authority with the mass targeting of minorities for searches. He agreed that the police had implemented "stop and frisk" in an illegal way, but he didn't think the practice itself was entirely bad.

So how does he think it should work instead? In his Daily News article, Adams discusses an incident last week when two officers in the Bronx were shot by a suspect while they responded to a 911 call about a suspicious man with a gun. According to the NYPD, the officers approached a man matching the description they received and asked him to show his hands. The man, 23-year-old Charlie Vasquez, reportedly produced a gun and shot at the officers.

Adams' conclusion:

The threat was neutralized. One more gun off the street. One more blow against the bad guys.

Yet there are some in our city who would say these officers should never have confronted Vasquez, that he never should have been stopped and questioned.

This is quite the straw man argument. Let's unpack it. These two officers did not, in fact, engage in any sort of "stop and frisk" at all. They approached a man who matched a description of somebody reportedly walking around with a gun. Before the officers were in a position to determine whether he was a suspect or even to question him, the man shot at them.

Adams doesn't indicate who, precisely, thinks the police shouldn't have confronted or questioned Vasquez. Perhaps that's because this wasn't the objection to "stop and frisk."

This is thoroughly uncontroversial policing. (Or most of it is. One of the officers might have accidentally shot the other during the confrontation.) Most people across the political spectrum want the cops to investigate a potentially dangerous person who may be up to criminal activity. The problem, as Adams well knows, is what the police actually end up doing. This isn't what "stop and frisk" looked like in New York City at all.

It is true, as Adams notes in his opinion piece, that the courts have recognized the police power to stop and search people if they have a reasonable suspicion that said person is suspected of a crime and they believe he is armed. But in New York City, "stop and frisk" actually resulted in hundreds of thousands of annual searches of predominantly minority men who it turned out were not armed and ended up not being arrested. In a 2014 report by the New York Civil Liberties Union, only two percent of police encounters under "stop and frisk" ever uncovered weapons. At the policy's height, NYPD officers were stopping nearly 700,000 people a year.

So why on earth is Adams attempting to use a case where a man was not even frisked—a case where the guy actually shot at police—as an example of some sort of "proper" stop and frisk? Because it's all about the guns. Adams, just like former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, is big on gun control. He is attempting to convince New Yorkers that some form of stop-and-frisk policy will be needed to keep the community safe from armed criminals.

It is unclear exactly what change Adams thinks will give the NYPD this power without returning the city to the level of abuse that Adams himself used to oppose. (His opposition to the status quo was real—when he was a state senator, he helped craft a law that purged NYPD database of the names of innocent people they searched.) Instead we get a vague theoretical defense of stopping and frisking people in some proper way, resting on an example that doesn't meet the normal definition of "stop and frisk." Adams fails to ask how the police might behave when they approach someone who turns out to be innocent.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"In a 2014 report by the New York Civil Liberties Union, only two percent of police encounters under "stop and frisk" ever uncovered weapons. At the policy's height, NYPD officers were stopping nearly 700,000 people a year."

So 14,000 illegal firearms off the street every year.

FTFY.

While I like the idea that any law prohibiting the bearing of arms is unconstitutional, under current interpretation it is not a violation of the 2A to arrest weapons-carriers or seize the weapon.

As for the use of "stop, interview and frisk", the SC has not ruled it to be a violation of the 4A.

It is no worse than having to stop your car at a road block to prove you're not drunk. Something that also produces a single digit percentage of "positive" results.

Arguing that it’s no worse than other searches without probable cause doesn’t fly around here. Or any place that values civil rights.

If you were Searching for a supplemental source of income? This is the easiest way I have found to earn $5000+ per week over the internet. Work for a few hours per week in your free time and get paid on a regular basis.HFe Only reliable internet connection and computer needed to get started…

Start today...........Earn-Opportunities

In NYC, all firearms are illegal firearms.

Undocumented firearms

Start earning today from $600 to $754 easily by working online from home. Last month i have generate and received $19663 from this job by giving this only maximum 2 hours a day of my life. Easiest job in the world and earning from this job are just awesome.MHf Everybody can now get this job and start earning cash online right now by just follow instructions click on this site...

For more info here.........VISIT HERE

Does "weapons" refer to guns only, or does it count people found with knives or batons or whatever?

Screwdrivers, fingernail clippers, kabobs...

Mean words and nasty stares.

Words are violence after all.

P38 can opener.

Where have heard something like that before? Oh right, “If it saves just one life….”

@Jerry B. The cops called 2% "weapons" because they can call a Swiss army knife or all sorts of innocuous items "weapons" they did not in fact find 14k "firearms".

This is the power of police dishonesty, they know it will translate in most brains exactly as it did in yours, and they were going for that very outcome.

So why on earth is Adams attempting to use a case where a man was not even frisked—a case where the guy actually shot at police—as an example of some sort of "proper" stop and frisk?

Because *Black* Lives Matter.

The obvious solution is legal open carry.

And bounties.

I actually have a great idea to disarm agents of the state other than tasers and require them to use bounty hunters to serve warrants. Much harder to inflict lethal force and no qualified immunity if the warrant is falsified or just wrong. You would have every single cop begging for bodycams in an instant.

It's sublime. Arm the citizens and not the state.

That's just how it worked in the early days of our country, before modern police forces existed. Warrants would be issued to aggrieved private citizens who would form their own "posses" to enforce them.

I have argued with people, that given the choice of citizens in fear of their government, or government in fear of its citizens, the latter is much more conducive to freedom. I find those opposed to be statists and cowards. You know, progressives.

Or legal conceal carry.

See, here's the problem with BLM going off the rails with their "police reform" bullshit. You can either support gangs of vicious criminals running around endangering your life and safety and security or you can support a different gang of vicious criminals running around endangering your life and safety and security as long as they promise to protect you from the first gang. The primary difference between the two gangs is that one of them will do it for free and you're legally allowed to defend yourself against them. The tragic thing about all this criminal activity is that the cops are going to be twice as bad as they ever were, but now they're going to be cheered for being thugs and criminals.

The primary difference between the two gangs is that one of them will do it for free and you're legally allowed to defend yourself against them.

I'm taking a pause here.

Why are comments locked on the rich famous white lady writer who achieved fame and fortune from falsely accusing and testifying against an innocent man ?

The contributor argues the wrongful conviction is why we should abolish sex offender registries and the stigma of being convicted of a sex offense but doesn't seem to believe Alice Sebold is responsible for the victim's life-ruining long incarceration.

No intention of reading her work or contributing to her wealth either way, but how durable is the claim "who achieved fame and fortune from falsely accusing and testifying against an innocent man"? As in, if she was raped and the books are popular despite having no resemblance to the events she went through or the man she accused, IDK, how true the statement you make is.

If she misidentified her attacker in her teens and made a mint off a horror/rape fantasy book/movie in her 20s, or 30s, as long as she wasn't the one keeping the man on the registry, I don't really see a reason for any animus, potentially the opposite; good on her for finding a lucrative outlet and fuck the system.

when's the suit against Sebold?

I too was having trouble commenting on that

I think they're trying to cut down on every thread starting with Fuck Joe Biden.

I object to that.

"Adams doesn't indicate who, precisely, thinks the police shouldn't have confronted or questioned Vasquez."

Come on, man. "Social justice" justice can only be served if absolutely everyone, including the perp, agrees. Or at least everyone who is not an establishment white supremacist patriarch.

And even then, we should demand that police use time machines to properly identify and then prevent crimes*.

*Again, the agreement on what constitutes a crime is fluid and best determined by professional grievance experts.

Or at least everyone who is not an establishment white supremacist patriarch.

Hey, the cop that probably shot her partner through the chest would be an establishment matriarch.

I watched the video. If she was injured it was almost certainly by ricocheting shrapnel. There is no way that guy shot her twice in her shooting arm based on the trajectories you can observe and on the five shots she got off after the suspects gun arm was restrained downward. Her first "eek" reaction doesn't appear to be to pain and is almost certainly due to the sound of the gun.

As an aside, watch the Crimestopper videos that follow this shooting. I can't believe anyone would walk in NY not carrying a gun.

Grievance experts will form one Panel and Equity Officers will form the second one. Between these two panels you have all the checks and balances you need to reach a socially just consensus.

What's wrong with that? We have the "proper kind" of racism, why not the proper kind of 4th amendment violations?

>>he didn't fully oppose the concept of "stop and frisk"

course not. dude's hardcore (D).

"Yet there are some in our city who would say these officers should never have confronted Vasquez, that he never should have been stopped and questioned."

On one hand I seriously wonder if enough people are stupid enough to buy this kind of gross equivocation. But on the other I realize that as long as what you want to do fits with their expectations, in this case gun control, most will just let it slide because it's for the "correct" reason after all.

test

So I can post in this topic but not in others?

Is my computer glitchy, or did Reason intentionally limit comments on today's "let's welcome convicted rapists back into polite society" piece?

Haven't analyzed it much further, but the article to which you refer is not the only one.

And another one.

Emily Horowitz is not interested in your opinion.

I just wanted to welcome the newest advocate for the Koch / Soros / Reason soft-on-crime agenda. 🙁

today's youth triggered even when you're nice.

Hire a fox to guard the hen house . . .

Is that as bad as hiring a hen to guard the fox house?

Is the hen protected by a large armed force?

Well if you can’t trust a New York mayor to sort this out, who CAN you trust?

The police were called to the scene at 8pm - '...there is a man with a gun...' They found the man with his hands in his pockets. When asked to take his hands out of his pockets he pulled out a gun and started firing. Adams is 100% correct that the cops had the right to 'stop and frisk' him but didn't get the chance.