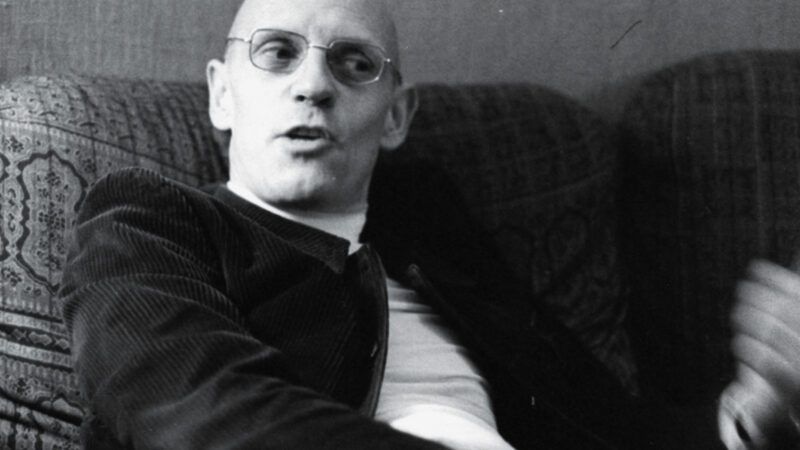

Foucault in the Panopticon

How Michel Foucault's encounters in Poland's heavily policed gay community informed his ideas

In 1958, the 32-year-old philosopher Michel Foucault arrived in Poland to assume the directorship of the Centre Français in Warsaw. Less than a year later, he abruptly left the country. According to a rumor that circulated for years, this rapid exit was precipitated by a sexual liaison with a young man who turned out to be on the payroll of the communist state's secret police. Amid the minor scandal that ensued, the French embassy requested Foucault's resignation and departure from Poland. His biographers have treated this Polish sojourn and the incident that brought it to an end as a footnote to his early career, covering it in a few pages.

In Foucault in Warsaw, first published in Polish in 2017 and now available in an English translation by Sean Gasper Bye, the philosopher Remigiusz Ryziński reconstructs this brief phase of Foucault's life on the basis of interviews, research in the copious files of the communist-era secret police, and speculation. The result is a hybrid work of literary reportage: part oral history, part archival detective story, part spy narrative, and part intellectual biography. The book is both the fragmentary story of Foucault's time in Warsaw and the story of Ryziński's effort to make sense of what really happened.

Ryziński elevates this narrative beyond mere biographical curiosity by using Foucault's experiences as a window into the secret history of gay life behind the Iron Curtain. Foucault had little to say about his time in Poland, so Ryziński's reconstruction relies heavily on the recollections of several men the French philosopher came into contact with while there. In the process of narrating their lives, he also makes the case that Foucault's thinking was shaped by his contact with these young men and the clandestine subculture they inhabited.

Foucault is perhaps best known for his account of the panopticon, a model prison first devised by the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century. The panopticon was a circular multi-level building in which cells were arranged around a central observation tower. Since the inhabitants of the cells never know when a guard might be observing them, they must assume they are always being watched and act accordingly. For Foucault, the panopticon illustrated the functioning of the "disciplinary apparatuses" characteristic of modern societies—a category in which he included not only prisons, asylums, and military barracks but also schools, factories, and hospitals. These institutions, he argued, condition their subjects' behavior not by monitoring them at all times but by leading them to internalize the gaze of authority.

Ryziński pored over the archives of Communist Poland's most notable surveillance apparatus—the secret police—for more than a year, searching for traces of Foucault's time in the country. Eventually, his investigations led him to files related to the man whose affair with Foucault occasioned the latter's expulsion from Poland. The man's name, he determined, was Jurek, and he was indeed a police informant—and not the only one operating amid the circles of gay men the philosopher encountered.

Homosexual acts were not strictly illegal in Communist Poland, but the state compiled extensive dossiers on those who engaged in them. Their motive was less moral disapproval than concern about their potentially subversive effects. Ryziński quotes a secret police document that states: "Like Freemasonry in former times, homosexuality remains an underground activity in all societies….Persecuted from the outside, homosexuals feel solidarity with one another (like every persecuted minority). The community of perversion connects people with adverse worldviews." The document adds that gays "recognize each other by signs, behaviors, and means of expression that are imperceptible to normal people." The perceived danger of homosexuality, it seems, resided not in the sexual act itself but in the consequences of its marginalization: tight in-group solidarity, the creation of an illegible argot, and so on. As Ryziński observes, "compiling a list of homosexuals could be the same as compiling a list of 'enemies of the nation.'"

Contrary to what one might assume, Foucault argued that panoptic surveillance does not necessarily seek to eliminate the transgressive behaviors it targets. This is because the perpetuation and expansion of power feeds upon the inevitable resistances it generates. Similarly, Ryziński suggests that the systematic police infiltration of Warsaw's gay male demimonde did not entail an effort to stamp out homosexuality. A subversive subculture could prove useful to the authorities' designs. They could, in the words of one document that Ryziński quotes, "be taken advantage of operationally." The apparent instrumentalization of a young informant in the expulsion of an ideologically problematic French academic provides one example of how this cultivation served power.

Ryziński argues that Foucault's experiences in Poland directly influenced the elaboration of this and other notable theories. When he arrived, Foucault had published only one book, Mental Illness and Psychology, which he would later disavow. During his year in Warsaw, he completed the major work that would set the course of his career as a mature thinker: History of Madness, which was first published in France two years after he left Poland. "Madness," Ryziński notes, "was a category of social exclusion in the same way as homosexuality." In this respect, he argues, "History of Madness was Foucault's attempt to understand himself."

According to Ryziński, Foucault's encounters with Poland's heavily policed gay community informed his scholarly examination of the treatment of the insane. "Madness and homosexuality are similar to one another," Ryziński writes, because as "long as there is no knowledge about them—medical, statistical, political—they do not exist. Or rather: they are left in peace." Conversely, as "the secret police agents gathered material on gay people, they were seeking a pathology that would give them the certainty that they had everything under control. In [History of Madness], Foucault described this same mechanism in relation to madness." Foucault's conception of "power/knowledge" proposes the latter two concepts are inextricable. Medical classification and social exclusion, he argued across several works, have long gone hand in hand.

In addition to this suggestive account of the genesis of Foucault's key ideas, Foucault in Warsaw offers new insights into the evolution of the philosopher's politics. Many on the right regard Foucault as one of a number of European leftists who led intellectuals astray in the wake of the 1960s. In reality, Foucault's political leanings were more complex. Years before he went to Warsaw, he had briefly been a member of the French Communist Party, but throughout his adulthood he was critical of "really existing socialism" and its Western defenders. In the early 1980s he petitioned on behalf of the independent Polish labor union Solidarity, and he returned to Poland after more than 20 years as part of a humanitarian aid mission. Ryziński's account suggests that his early run-in with a communist state helped infuse him with a skepticism of Marxism not shared by most of his French intellectual contemporaries.

For Ryziński, though, the hero of Foucault in Warsaw is less the philosopher than the otherwise unknown young Polish men Foucault met in the late '50s. In his research for the book, Ryziński managed to track down several of them. They had given little thought, it seems, to the young French academic who had once frequented their circles. Through decades of marginality, surveillance, and persecution, these men sustained communities and found love among each other. Their quiet perseverance, Ryziński implies, evokes an enigmatic phrase from Foucault's History of Madness that serves as the epigraph of his book: "the stubborn, bright sun of Polish liberty."

Foucault in Warsaw, by Remigiusz Ryziński, translated by Sean Gasper Bye, Open Letter, 220 pages, $15.95

Show Comments (154)