Leaving Uzbekistan

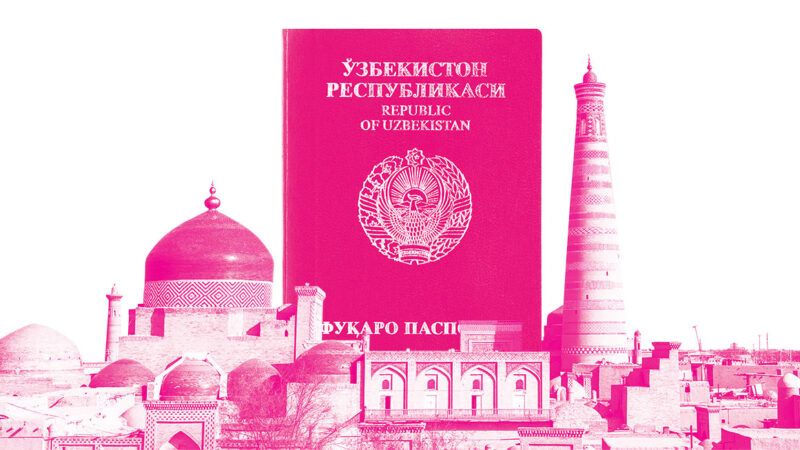

Why is it so hard for Uzbek citizens to get permission to travel abroad?

Reason's December special issue marks the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the Soviet Union. This story is part of our exploration of the global legacy of that evil empire, and our effort to be certain that the dire consequences of communism are not forgotten.

Entering most countries is already an overly bureaucratic process. But if you have to do a lot of paperwork to leave a country, that's when you know the fix is in.

Exit visas have long been a hallmark of authoritarian regimes. The Soviet Union was no exception, requiring its citizens to get explicit permission to leave the country. It was thus with great fanfare that the 1993 constitution of the new, post-communist Russian Federation abolished this requirement, allowing citizens to travel abroad without permission. Most former Soviet republics quickly followed suit.

Not Uzbekistan, however. It has the dubious distinction of being the last post-Soviet republic to abolish its system of exit visas—in 2019, a good seven years after Cuba managed to do the same. For nearly 30 years, Uzbeks could travel visa-free only to other former Soviet republics.

That this practice lingered on in the Central Asian nation perhaps shouldn't be too surprising. Like many of its neighbors, Uzbekistan's transition to post-communist rule brought few improvements for life or liberty.

The old Communist Party boss in charge at the breakup of the Soviet Union, Islam Karimov, kept on trucking as the president of the newly independent Uzbekistan and managed to stay in power until his death in 2016. A New York Times obituary describes Karimov as a "ruthless autocrat" who crushed press freedom, massacred opposition demonstrators, and ruled with the aid of secret police.

Even so, Uzbekistan's decision to keep its exit visa system in place aroused no shortage of international attention and controversy.

A 2007 United Nations report on human rights abuses singled out these visas for special criticism, noting that they could "be easily used to stop human rights defenders from leaving the country." The same report said exit visas violated international law as well as the Uzbek Constitution's own guarantee to its citizens of freedom of movement into and out of the country.

Karimov's death has led to a modest opening of Uzbekistan, which includes an end to the exit visa system. In August 2017, the country's new president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, issued a decree allowing citizens to travel abroad without government permission starting in January 2019.

Mirziyoyev has also liberalized trade and travel into the famously isolated country. Independent news websites have been unblocked by the government, and some foreign journalists have even been allowed to report from inside Uzbekistan.

Nevertheless, the nation still ranks toward the bottom of most international indexes on press and political freedom. Its security services routinely violate people's rights. But Uzbek citizens who dislike this persistent authoritarianism at least now will have an easier time getting away from it.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (14)