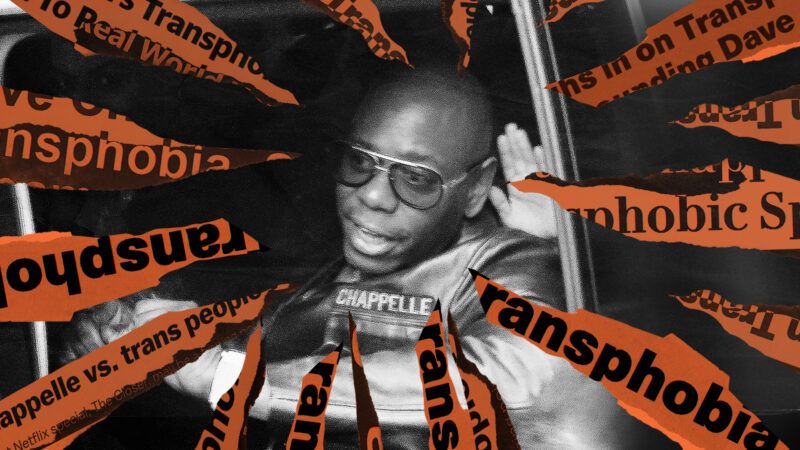

Netflix CEO Apologizes for Having Principles

When employees tried their hand at a shakedown, CEO Ted Sarandos buckled a bit under the pressure.

There's really no good reason why we should still be talking about Dave Chappelle's 2-week-old standup special The Closer. Except that Netflix employees have wielded it as means of inserting themselves into high-level company affairs, demanding that the company accede to their demands, seemingly as penance for its decision to platform Chappelle.

For people who have actually committed an hour of their time to watching the special, it's a stretch to portray Chappelle as a man with animus toward the trans community. He makes a point of opposing North Carolina's bathroom bills, which would bar transgender people from using the bathroom of their choice, saying that no American should have to show their birth certificate to take a shit in a Walmart bathroom (true). He attempts to delineate the difference between such mean-spirited laws and feeling annoyed by the quickly changing elite consensus that we must actively cheer on the transgender rights movement, as opposed to just not being all that interested in the demands of a niche subgroup. He closes with a tale of his friend, the transgender comic Daphne Dorman, who committed suicide purportedly after facing online fury from people in the trans community (though Chappelle takes care not to assign a singular cause to her decision to take her own life). The through line is a commentary on the plight of the black man in America, along with a lamentation that it's terribly easy for people to get barred from polite society, immediately and retroactively, for committing acts or uttering words that offend people's poorly-calibrated sensibilities.

The special is characteristically irreverent—which you should expect if you've seen literally anything that Chappelle has ever worked on before. And it created such a firestorm of internal criticism that Netflix's trans employee resource group organized a walkout, which took place earlier today, while laying a list of demands at the feet of Netflix executives.

I'm so happy I didn't do my eye makeup yet because now I'm sobbing. How did our little group turn into this? ????

So much love to all of you right now, from the bottom of my heart ???? ????️⚧️???? #NetflixWalkout https://t.co/SM99Nd732X

— Terra Field is ????️⚧️ Visibly Pissed ????️⚧️ (@RainofTerra) October 20, 2021

The walkout itself didn't amount to much (a not-huge crowd of Netflix employees, plus some counter protesters with cutely tepid signs like "We like Dave" and "I like jokes"), but Twitter really wanted users to believe it was a big deal, promoting the walkout as a trending moment. Several prominent actors and comedians, like Elliot Page and Wanda Sykes, drummed up support for the protest. The protesters' demands, which interestingly do not actually call for deplatforming Chappelle, involve specific asks: the company must add disclaimers before transphobic or hate speech-promoting content; suggest "trans-affirming" content alongside content deemed transphobic; "hire trans and non-binary content executives, especially BIPOC, in leading positions"; create a new fund that specifically cultivates and platforms work by trans and non-binary creators; and revise the processes involved in curating transphobic content. Having pried the door open, low-level transgender rights activist-employees are trying to force Netflix executives to engage in affirmative action and aggressive content moderation.

OK, the demands from the trans employee resource group (ERG) are WILD. Note that they don't call for deplatforming, interestingly, but for all kinds of affirmative action & "hate speech" flagging measures. They're framing it as if they're owed reparations, concessions, etc. https://t.co/ywtqZyOlbz pic.twitter.com/Lhq5pr7a36

— Liz Wolfe (@LizWolfeReason) October 20, 2021

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos, who had recently defended Chappelle in a letter to employees ("content on screen doesn't directly translate to real-world harm," he wrote) now says he miscalculated. "I should have led with a lot more humanity. … I had a group of employees who were definitely feeling pain and hurt from a decision we made," he told Variety. "Because we're trying to entertain the world, and the world is made up of folks with a lot of different sensibilities and beliefs and senses of humor and all those things — sometimes, there will be things on Netflix that you dislike," Sarandos continued, saying they'll draw the line at content that calls for intentionally "physically harming other people" and hyping the company's "creative equity fund," which supports trans and non-binary content creators. Sarandos' did not reiterate his initial question of whether content that appears on screen will "directly translate to real-world harm."

It's good that Sarandos hasn't fully backed down from his defense of supplying artistic freedom to creators who partner with Netflix, and it's perfectly reasonable for CEOs to want to cultivate content that appeals to different subgroups. But he blundered by ceding ground to a small group of employees who are making radical demands concerning the structure and priorities of a massive company with customers all over the world. After initially defending a good decision, Sarandos looks a bit like another CEO in a long line whose employees successfully held their feet to the fire, demanding a digital world littered with content warnings and a physical world filled with diversity hires.

This moment of moral panic is predicated on the idea that portrayal or discussion of bad actions in some way leads more people to commit terrible acts that end up harming the physical safety of vulnerable people. We don't have good data to indicate this (except perhaps when it comes to portrayal of suicides, where data better bears out the idea of a contagion effect), but people uncritically fling this concept around, rarely pausing to ask whether Chappelle's jokes about trans people carry a radicalizing power that converts otherwise benevolent decent people into violent transphobes. We have no evidence to indicate they do, and for whatever reason, this essential question has been repeatedly pushed aside, as if it bears no relevance to how we should forge ahead.

Show Comments (94)