Why Don't More Countries Enforce the Airport Security Rules That the TSA Says Are Essential?

While liquid limits are common, America's shoe removal policy is nearly unique, and many countries allow small pocket knives.

"Mommy, do we need to take our shoes off again?" the little American girl asked as she stood in a security line at a German airport with her four younger siblings. Her mother said yes, prompting a more experienced traveler to correct her: "Actually, here you do not."

According to the bystander, who described the incident on FlyerTalk, a forum for frequent travelers, "Mommy ignored me. The little girl turned around, and I pointed out several people going through the [metal detector] without removing their shoes." At this point another American in the line "removed his lace-ups and ordered his wife to do the same, even though security told him it wasn't necessary." His example "caused a chain reaction of shoe removal," and "Mommy had the child help remove four other pairs of shoes."

Notwithstanding that anecdote, Americans who travel to other countries are apt to notice that their airport security rituals often depart from the rules to which we have become accustomed in the United States since 9/11. Those differences call into question the judgment of American policy makers who insist that precautions much of the world does without are essential in preventing terrorist attacks. Here are a few of the more conspicuous examples.

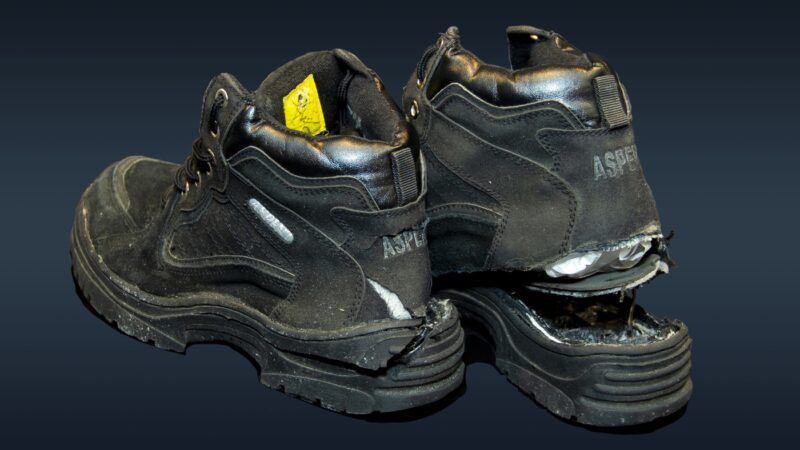

Shoe Removal

Richard Reid, who unsuccessfully tried to ignite 50 grams of PETN explosive concealed in his shoes during an American Airlines flight from Paris to Miami a few months after the 9/11 attacks, is serving a life sentence at the federal "supermax" prison in Florence, Colorado. But travelers are reminded of him every time they board a flight in the United States, because his plot inspired the long-standing requirement that airline passengers remove their shoes at security checkpoints and place them in a bin that travels on a conveyor belt through an X-ray machine.

That did not happen right away. As late as August 9, 2006, nearly five years after Reid became notorious as a would-be Al Qaeda "shoe bomber," the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) was still advising air travelers that "you don't have to remove your shoes before you enter the walk-through metal detector." A week later, the TSA began saying "you are required to remove your shoes before you enter the walk-through metal detector." The TSA says it changed the policy "based on intelligence pointing to a continuing threat" from shoe bombs.

How big a danger Reid himself posed is debatable. He attracted flight attendant Hermis Moutardier's notice because he repeatedly lit matches while vainly attempting to ignite a fuse that ran through a sweat-dampened shoelace. Initially Moutardier told him smoking was prohibited, and he promised to comply. But when she found him leaning over in his seat, she asked what he was doing, at which point he reached to grab her, revealing a shoe in his lap and another lit match. Passengers subdued Reid before he could try yet again to set off the bomb.

John Mueller, a terrorism expert at the Ohio State University and a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, notes that PETN "is fairly stable and difficult to detonate," even when the fuse is dry. "The best detonators are metallic," he writes, "and these are likely to be spotted by the metal detectors passengers and their carry-on baggage were subjected to well before 9/11." Mueller also thinks it is unclear "whether Reid's bomb would have downed the airplane if he had been able to detonate it." He notes that "a similar bomb with 100 grams of the explosive"—twice as much as Reid had—that was "hidden on, or in, the body of a suicide bomber and detonated in 2009 in the presence of his intended victim, a Saudi prince, killed the bomber but only slightly wounded his target a few feet away."

After thinking about it for more than four years, the TSA nevertheless decided that the possibility of Reid copycats was a serious enough threat to justify mandatory shoe removal, a policy that remains in force to this day. As international travelers can attest, the United States is nearly unique in imposing that requirement. In their 2017 book about aviation security, Are We Safe Enough?, Mueller and Mark G. Stewart, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Newcastle in Australia, note that European Union countries "do not require the removal of shoes at the screening checkpoint." Australia, Canada, China, India, Israel, Japan, Mexico, and the U.K. likewise do not routinely require shoe removal.

A discussion of the subject on FlyerTalk identified just two countries that copy the U.S. policy on shoes: Russia and the Philippines. Another thread on the same forum also mentioned Belize and Sri Lanka.

Of the countries that don't require shoe removal, Israel is perhaps the most striking example, since it has always faced a relatively high risk of terrorist attacks and operates what is often described as the most secure airport in the world. "No flight leaving the [Ben Gurion International Airport in Lod] has ever been hijacked," CNN notes, "and there has not been a terrorist attack at the airport since 1972." In 2016, former TSA Administrator John S. Pistole estimated that Israel spends "about 10 times as much as we spend here in the U.S. per passenger." Israeli security personnel, who tend to be much better trained than your average TSA officer, rely heavily on selective grilling of passengers, which has frequently provoked complaints of racial profiling. Yet despite its intensive precautions, the Israeli government lets passengers keep their shoes on.

A decade ago, Janet Napolitano, who then oversaw the TSA as secretary of homeland security, predicted that the shoe removal policy would be phased out "in the months and years ahead" as a result of new screening technology. The Washington Post, which reported Napolitano's comments, noted that "there hasn't been another shoe bomb attempt" since Reid's fiasco, and "aviation security experts question whether shoe removal is necessary."

One of those experts was the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Yossi Sheffi, who was born in Israel. "You don't take your shoes off anywhere but in the U.S.—not in Israel, in Amsterdam, in London," he told the Post. "We all know why we do it here, but this seems to be a make-everybody-feel-good thing rather than a necessity."

Pistole, then head of the TSA, cited survey data indicating that "shoe removal was second only to the high price of tickets in passenger complaints." He nevertheless defended the policy. "We have had over 5.5 [billion] people travel since Richard Reid," he said, "and there have been no shoe bombs because we have people take their shoes off."

A few months ago, Axios reported that Napolitano's prediction could finally come true, thanks to floor-embedded electromagnetic shoe scanners developed by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). The PNNL has licensed that technology to Liberty Defense Holdings.

"Removing shoes at the TSA checkpoint is one of the most inconvenient rituals of flying in the U.S.," Axios said. "Adding the shoe scanner could speed up the screening process by 15 to 20 percent, according to Liberty CEO Bill Frain….Eventually, the goal is to screen passengers without stopping as they pass through a tunnel toward the airport gate."

When might that happen? Axios said Liberty planned to start installing its machines at airports "in about 18 months."

Liquid Limits

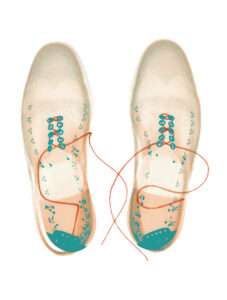

After British police foiled a terrorist plot to attack transatlantic flights with liquid explosives disguised as soft drinks in August 2006, the TSA initially prohibited passengers from carrying any liquids, gels, or aerosols, except for baby formula and prescription medicine, onto airplanes. A month later, it modified the rule, allowing up to 100 milliliters (3.4 fluid ounces) of liquid per container. All such containers (typically toiletries) are supposed to be placed in a single quart-sized plastic bag, which has to be removed from carry-on luggage and placed in a bin to be scanned at the security checkpoint. There is an exception for "medically required liquids," including over-the-counter drugs and contact lens solution, which can exceed 3.4 ounces, don't need to fit in the plastic bag, but are supposed to be announced when you go through security.

A year after the TSA imposed its liquid restrictions, then–TSA Administrator Kip Hawley told The New York Times the rules were aimed at limiting not just the total volume of liquid but also the size of each container, because "with certain explosives you need to have a certain critical diameter in order to achieve an explosion that will cause a certain amount of damage." But since the TSA does not stop passengers from taking empty containers (such as water bottles) into the cabin, it seems like limiting the total amount of liquid would still be important.

Is the TSA actually managing to do that? Based on personal experience, I have my doubts (even leaving aside the exception for "medically required liquids," which could cover, e.g., a 16-ounce bottle labeled as contact lens solution). Until recently, I did not realize that passengers officially are limited to just one bag of toiletries each. I had always used two, which was never a problem. I also frequently have forgotten about liquids and gels remaining in my carry-on bags (such as toothpaste, mouthwash, hand sanitizer, and eyeglass cleaner), and they have never been flagged by TSA screeners. Other American travelers report similar experiences.

One thing that caused me unexpected trouble: A couple of years after the restrictions took effect, for reasons too complicated to explain here, my wife and I tried to fly from Dallas to Addis Ababa with cans of refried beans in our carry-on bags. That led to a dispute about whether refried beans qualified as a solid, as I maintained, or as a liquid, as a TSA supervisor ultimately decided.

In March 2020, the TSA responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by allowing up to 12 ounces of hand sanitizer in airplane cabins, which makes you wonder whether the usual three-ounce rule is unnecessarily strict. Couldn't terrorists take advantage of the new allowance by carrying liquid explosive in 12-ounce hand sanitizer bottles? And if that risk is acceptable, why isn't four ounces of shampoo or six ounces of pineapple juice?

Bruce Schneier, a security expert, sometime TSA adviser, and longtime skeptic of the agency's liquid limits, thought the hand-sanitizer exception proved his point. "Won't airplanes blow up as a result?" he asked in a blog post last year. "Of course not. Would they have blown up last week were the restrictions lifted back then? Of course not. It's always been security theater."

Unlike mandatory shoe removal, however, liquid limits are common internationally. The rules are essentially the same in the U.K. (where the would-be liquid bombers were arrested), European Union countries, Canada, China, India, and Mexico, for example. But there are exceptions, including for domestic travelers in Australia, Brazil, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, and New Zealand. Some countries enforce liquid limits for international travelers only if they are flying to countries with those rules.

The Israeli airline El Al advises passengers that "most airports in the world have adopted the model implemented in the United States and the European Union regarding liquids permitted aboard in hand baggage." The airline says it enforces those rules for passengers flying to "the United States, European Union countries, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, China, Hong Kong, Mumbai (India), Bangkok (Thailand) and Johannesburg (South Africa)." El Al also notes that "it is not permitted to bring liquids and sprays of any kind"—except for "medications and baby food"—"on board flights departing from the airports in Moscow and St. Petersburg." That suggests the liquid limits don't apply to other El Al destinations.

According to Japan Airlines, liquids are restricted on international flights departing from Japan, East Asia, Vietnam, Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, Brazil, Singapore, Malaysia, and Dubai. It says the liquid limits apply to all flights departing from the U.S., the U.K., E.U. countries, Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, Canada, India, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Russia. Again, that seems to mean passengers flying from or within other countries served by Japan Airlines are free to carry on beverages and toiletries that exceed 100 milliliters.

While liquid explosives "can be very powerful," Stewart says, they "are not a new phenomenon. They have been around forever. So for them to suddenly become a 'threat' in 2006 is fanciful and a knee-jerk reaction. They may be harder to detect during screening, so there is a vulnerability there, but that vulnerability existed decades before 2006." Yet "if the U.S. mandates a certain aviation security rule, the rest of the world sort of has to follow if they want to fly to the U.S. or even have passengers transiting, so the implications are global."

Critics of the TSA's liquid limits argue that they distract screeners from more serious threats. The same screeners who can be counted on to make you toss or empty your water bottle seem to be very bad at spotting weapons. In 2015, Mueller and Stewart note, the Department of Homeland Security's Office of the Inspector General reported that "US airport screening failed to detect mock weapons in 95% of tests."

Schneier asked Hawley about the TSA's liquid policy during a 2007 interview. "By today's rules," Schneier noted, "I can carry on liquids in quantities of three ounces or less, unless they're in larger bottles. But I can carry on multiple three-ounce bottles. Or a single larger bottle with a non-prescription medicine label, like contact lens fluid. It all has to fit inside a one-quart plastic bag, except for that large bottle of contact lens fluid. And if you confiscate my liquids, you're going to toss them into a large pile right next to the screening station—which you would never do if anyone thought they were actually dangerous. Can you please convince me there's not an Office for Annoying Air Travelers making this sort of stuff up?"

After a jokey response, Hawley said this: "I often read blog posts about how someone could just take all their three-ounce bottles—or take bottles from others on the plane—and combine them into a larger container to make a bomb. I can't get into the specifics, but our explosives research shows this is not a viable option."

Hawley did promise that "in the near future, we'll come up with an automated system to take care of liquids, and everyone will be happier." That was 14 years ago.

Prohibited Items

Since the 9/11 hijackers used knives and box cutters against crew members and passengers, it is not surprising that the TSA responded by banning such tools from airplane cabins. It is harder to understand why those items are still prohibited 20 years later, despite hardened cockpit doors and other precautions that make a takeover with similar weapons hard to imagine nowadays. In addition to those potent symbols of the 2001 attacks, the agency's list of prohibited items includes more than 100 other entries. Many of these—e.g., weapons such as guns and grenades, along with flammable substances such as gasoline and propane—make intuitive sense, while others are more debatable and sometimes downright puzzling.

Foam toy swords are forbidden, for example, perhaps because the TSA thinks they qualify as "realistic replicas" of actual weapons, another category of prohibited items. Also banned: Magic 8-Balls (too much liquid) and myriad kinds of sharp, pointy, or heavy equipment, including corkscrews or pocket tools with blades, darts, drill bits, baseball bats, golf clubs, pool cues, hammers, long screwdrivers, snow cleats, bowling pins, hiking poles, walking sticks, cutting boards, and cast iron pans. Any of these could conceivably be used as a weapon, but so could bowling balls, stick pins, nail files, or knitting needles, all of which are permitted.

In 2005, the TSA began allowing passengers to carry on some common tools, including screwdrivers shorter than seven inches and scissors with blades shorter than four inches. "The TSA's internal studies show that carry-on-item screeners spend half of their screening time searching for cigarette lighters, a recently banned item, and that they open 1 out of every 4 bags to remove a pair of scissors," The Washington Post reported. "Officials believe that other security measures now in place, such as hardened cockpit doors, would prevent a terrorist from commandeering an aircraft with box cutters or scissors."

That last observation suggests that the risk from box cutters and pocket knives, which remain banned two decades after 9/11, might be tolerable. But the Association of Flight Attendants thought even the modest changes that the TSA implemented in 2005 went too far. "TSA needs to take a moment to reflect on why [the rules] were created in the first place—after the world had seen how ordinary household items could create such devastation," a spokeswoman for the union said. "When weapons are allowed back on board an aircraft, the pilots will be able to land the plane safely, but the aisles will be running with blood."

Sixteen years later, the aisles still are not running with blood, notwithstanding the TSA's tolerance of short scissors and screwdrivers. But opposition from flight attendants and other alarmists defeated another attempted loosening of the TSA's rules in 2013.

That March, the TSA announced that "small knives"—with blades no longer than six centimeters (2.36 inches) and no wider than half an inch—would "soon be permitted in carry-on luggage." It said the decision "was made as part of TSA's overall risk-based security approach and aligns TSA with International Civil Aviation Organization Standards and our European counterparts." A TSA spokesman explained that the agency's "risk-based security approach" allowed TSA officers "to better focus their efforts on finding higher-threat items such as explosives." In addition to short knives, the TSA said it would allow miniature baseball bats, lacrosse and hockey sticks, pool cues, ski poles, and up to two golf clubs per passenger.

Members of Congress were outraged. "While reinforced cockpit doors make it harder for a terrorist to harm pilots or gain control of an airplane," then-Rep. Edward Markey (D–Mass.), who is now a senator, complained in a March 9 letter to Pistole, "they do nothing to protect the lives of the passengers and flight attendants in the main cabin." Three days later, Markey introduced a bill, the No Knives Act of 2013, that would have overridden the TSA's judgment by requiring the Department of Homeland Security to "prohibit airplane passengers from bringing aboard a passenger aircraft any item that was prohibited as of March 1, 2013." The bill attracted 63 co-sponsors, including 52 Democrats and 11 Republicans.

In response to objections from legislators, flight attendants, and air marshals, the TSA initially stood its ground. "We recognize that knives can do harm," a spokesman said, "but we also recognize that there are a number of other items that people can carry on that can do just as much harm." Although small scissors and nail files had been allowed in airplane cabins since 2005, he said, "we have not had one case that we're aware of where [one of those items] has caused harm to a passenger or crew member."

At a congressional hearing on March 14, Pistole likewise noted that weapons could be improvised with items already allowed in airplane cabins. Given "hardened cockpit doors" and "the demonstrated willingness of passengers to intervene to assist flight crew during a security incident," he added, "a small pocket knife is simply not going to result in the catastrophic failure of an aircraft."

Ignoring the storm clouds, Gear Patrol greeted the new TSA policy with an article recommending the "5 Best TSA-Approved Pocket Knives," which is still the top result when you do a Google search for "TSA maximum knife length." A few weeks later, however, the TSA said it was "temporarily delay[ing] implementation" of the new rule, which had been scheduled to take effect on April 25, to "accommodate further input from the Aviation Security Advisory Committee," which "includes representatives from the aviation community, passenger advocates, law enforcement experts, and other stakeholders." (Stakeholding, by the way, is not something you want to be caught doing in an airport security line.)

On June 5, the TSA officially reneged on its promise of pocket-knife tolerance after "extensive engagement with the Aviation Security Advisory Committee, law enforcement officials, passenger advocates, and other important stakeholders." The Association of Flight Attendants, which campaigned against the new policy under the slogan "No Knives on Planes Ever Again," celebrated, calling the TSA's capitulation "a good lesson in collective action."

According to data from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, knives and "other cutting instruments" (not including box cutters) accounted for two-fifths of "prohibited items intercepted at airport screening checkpoints" from 2002 through 2008 (the last year for which detailed numbers are available). During that period, TSA screeners confiscated more than 22 million tools in those categories, and they surely missed a lot. Someone I know (not me!) routinely carries a Leatherman pocket tool that includes a small blade, for example, and frequently forgets to leave it at home when he flies, in which case he drops it into his backpack along with his other pocket contents. Typically no one notices.

Other countries often have shorter lists of items that are prohibited in carry-on bags. The British Civil Aviation Authority, for example, allows knives with blades no longer than six centimeters—the rule that the TSA tried to implement in 2013. Evidently British "stakeholders" are not as noisy as their American counterparts. Also unlike the TSA, the U.K. tolerates walking sticks and pool cues. It says nothing about bowling pins.

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency likewise allows short knives, and so do Mexico's Federal Civil Aviation Agency and the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority. Canada even tolerates lawn darts, which the TSA surely would prohibit if they were still legal in the United States. Canada allows tent poles, which the TSA does not, but draws the line at tent stakes.

Alligator Repellant

Like the shoe and liquid rules, the TSA's list of prohibited items seems pretty arbitrary. Mueller says "it's not clear" that any of these three policies "reduce risk enough to justify the cost, but that can be said about a lot of security measures."

As the TSA's doomed plan to allow pocket knives shows, security rules are much easier to establish than they are to loosen or lift. Logically, the fact that the TSA has seen fit to impose a restriction proves nothing about its cost-effectiveness. But politically, it creates a presumption that is hard to rebut, even when the U.S. government is nearly alone in thinking the policy makes sense.

To many people, the dearth of shoe bombings since Reid tried one in 2001 suggests that maybe it's not necessary to insist that passengers take off their shoes before they board their flights. But in Pistole's mind, it proved the effectiveness of mandatory shoe removal.

Pistole's reasoning is reminiscent of an argument between two Muppets. When Bert asked Ernie why he had a banana in his ear, Ernie replied that "I use this banana to keep the alligators away." An exasperated Bert noted that "there are no alligators on Sesame Street!" That fact, Ernie argued, proved his safeguard was "doing a good job." The difference is that Ernie was kidding.

Show Comments (53)