The FDA Is Set To Unintentionally Push Quitters Back to Smoking

Instead of trusting the science, the FDA will treat adults like children.

The week ahead will be hugely consequential for the future of tobacco and nicotine in the United States. On September 9, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must meet a court-imposed deadline to decide which electronic cigarette and vapor products will be allowed to remain on the market. The agency's decisions will affect more than just the livelihoods of small business owners and big vaping companies; at stake are the rights of millions of current and former smokers to access a safer alternative that could literally save their lives.

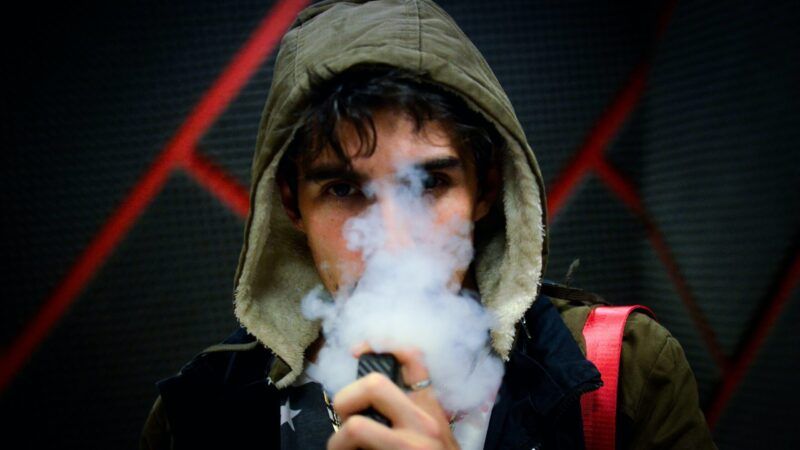

American news coverage of vaping has tended to focus on its downsides, particularly the use of e-cigarettes among teens and adolescents. Legislators and activist groups have raised the alarm about youth vaping to encourage the FDA to enact de facto prohibition of flavored products. In the popular imagination, vaping seduces youth into dangerous addiction and renormalizes tobacco use, justifying bans on the sale of e-cigarettes even to adults.

The story is considerably more nuanced among experts in the field of tobacco control.

Advocates of harm reduction do not dismiss genuine concerns over youth use of nicotine products, but they also focus on the long-term goal of preventing deaths caused by smoking. They note that the best available evidence suggests that vaping is far safer than smoking cigarettes, that it is more effective than nicotine patches or gums at helping smokers quit, and that the health benefits of encouraging smokers to switch outweigh the harms of vaping under almost all circumstances.

Kenneth Warner and David Mendez, both of the University of Michigan School of Public Health, illustrated this in a study last year that simulated 360 different scenarios for how vaping could impact American health through the end of the century. In 99 percent of those scenarios, the outcomes were positive for life-years saved. Similarly, modeling published by David Levy of Georgetown University and other researchers in the journal Tobacco Control projects that widespread switching from smoking to vaping would prevent between 1.6 million and 6.6 million premature deaths by 2100.

That transition to lower-risk sources of nicotine will only occur if smokers are provided with accurate information about vaping and if adults are allowed to buy products appealing enough to compete with cigarettes. Unfortunately, alarmist news coverage and prohibitive policies are consistently failing smokers. The situation is sufficiently dire that Warner and 14 other prominent experts in tobacco control, all of them past presidents of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, issued a joint article in August warning that the opportunity to save lives through harm reduction may be missed.

"We believe the potential lifesaving benefits of e-cigarettes for adult smokers deserve attention equal to the risks to youths," they wrote in the American Journal of Public Health. They noted that the public has a distorted view of the risks of vaping, with many falsely believing it to be equally as harmful as smoking, and that adults are increasingly denied access to flavored vapor products that can help them quit. "The singular focus of US policies on decreasing youth vaping," they wrote, "may well have reduced vaping's potential contribution to reducing adult smoking."

While policies should seek to discourage youth vaping, it's important to keep that problem in perspective. Rates of use are already declining from their peak. Most vitally, youth smoking (a far more dangerous behavior than vaping) has fallen to the lowest rates in modern American history at the same time that vaping has risen in popularity, contradicting fears that vaping will be a gateway to cigarettes. Research evaluating the effects of a ban on flavored e-cigarettes in San Francisco suggests that it may have unintentionally increased the use of combustible tobacco among teens. Challenging tradeoffs like these are inherent to tobacco control and policies that do not take them seriously will often fail to achieve their intended aims.

That brings us to the difficult decisions the FDA must now make about the future of vaping. The law the agency is tasked with enforcing was passed in 2009, years before the unanticipated rise of e-cigarettes. Backed and negotiated by tobacco giant Philip Morris, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act was designed for a more stagnant market. It grandfathered in nearly all tobacco products that were sold before 2007 while subjecting newer products to an onerous and costly process of regulatory review. In practice, that means that lethal cigarettes continue to be freely sold, no questions asked, while lower-risk e-cigarettes are threatened with prohibition.

The FDA has struggled with how to apply this poorly designed law while balancing the potential for harm reduction with public demands for strict regulation. Given the scope of the market and the complexity of the issues, the FDA itself sought more time to develop a sensible regulatory framework. Under former Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, it would have delayed the deadline for applications until August 2022, but a misguided lawsuit brought by health groups forced an acceleration of the schedule.

Submitting testimony to court in 2019, the director of the FDA's Center for Tobacco Products warned that enforcing rapid compliance would eliminate many products from the market and drive smokers back to tobacco: "Dramatically and precipitously reducing availability of these products could present a serious risk that adults, especially former smokers, who currently use [e-cigarettes] and are addicted to nicotine would migrate to combustible tobacco products."

That is precisely the outcome that will occur on September 9 if the FDA takes a hardline approach to vapor product applications. The agency has already rejected 4.5 million applications from a single company for lacking environment assessments; more ominously, it also rejected 55,000 applications from manufacturers of flavored e-liquids last week and at least another 800 applications on Monday, reportedly all for products in flavors other than tobacco or menthol. Close watchers of the industry fear that this portends disaster for independent "open system" products that allow vapers to choose the flavors, nicotine concentrations, and physical components that work best for them.

It appears that the FDA's decisions will ultimately be determined less by the actual risks of the products involved than by the question of which companies have the resources to conduct expensive scientific trials. An ironic result of this would be that the e-cigarette brands most likely to survive this winnowing are those that are at least partially owned by "Big Tobacco" companies, who stand to gain massively from the anti-competitive effects of banning their smaller competitors.

It should be obvious that this is an irrational way to regulate vaping given that the relevant comparison is to lethally dangerous cigarettes, which remain widely available and essentially unchanged after 12 years of FDA regulation. Yet because the anti-smoking lobby has spent years encouraging moral panic about vaping and decades denigrating the rights of tobacco and nicotine consumers to make their own decisions, the pointless prohibition of a wide swath of far safer nicotine products will likely proceed without much protest from anyone but the small minority of vapers themselves.

The FDA's own incentives tilt toward appeasing anti-vaping groups and reducing its workload by setting an impossibly high bar for smaller e-cigarette and e-liquid companies, but in doing so it will perpetuate smoking. The more humane option would be for the FDA to use its discretion to keep many more products on the legal market, including open systems and nontobacco flavors, by recognizing the abundant evidence that vaping is driving down rates of smoking, helping smokers quit, and rendering the conventional cigarette obsolete.

Despite making tremendous progress to curb smoking, 34 million Americans still smoke and more than 400,000 of them die prematurely every year. The habit is disproportionately ingrained among the least well off, including those with low incomes, low levels of education, and mental illness. These smokers deserve better than the moral panic and demands for abstinence that dominate the discourse around nicotine use. For many, access to safer and more appealing options is a matter of life and death. To take that away from them would be a tragedy, one the FDA can avert by choosing harm reduction over prohibition.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I made over $700 per day using my mobile in part time. I recently got my 5th paycheck of $19,632 and all i was doing is to copy and paste work online. this home work makes me able to generate more cash daily easily.GHm simple to do work and regular income from this are just superb. Here what i am doing.

Try now................... VISIT HERE

Start making money this time… Spend more time with your family & relatives by doing jobs that only require you to have a computer and an internet access and you can have that at your home.GHj Start bringing up to $65,000 to $70,000 a month. I’ve started this job and earn a handsome income and now I am exchanging it with you, so you can do it too.

You can check it out here…........ VISIT HERE

Google pay 390$ reliably my last paycheck was $55000 working 10 hours out of consistently on the web. My increasingly youthful kinfolk mate has been averaging 20k all through continuous months and he works around 24 hours reliably.WEd I can't trust how direct it was once I attempted it out. This is my essential concern...:) For more info visit any tab on this site Thanks a lot ...

GOOD LUCK.............. VISIT HERE

Start making money this time… Spend more time with your family & relatives by doing jobs that only require you to have a computer and an internet access and you can have that at your home.GFs Start bringing up to $65,000 to $70,000 a month. I’ve started this job and earn a handsome income and now I am exchanging it with you, so you can do it too.

You can check it out here…............. VISIT HERE

If you were looking for a way to earn some extra income every week... Look no more!!!! Here is a great opportunity for everyone to make $95/per hour by working in your free time on your computer from home...KJQ I've been doing this for 6 months now and last month i've earned my first five-figure paycheck ever!!!! Learn more about it on following link... WorkJoin1

The FDA's own incentives tilt toward appeasing anti-vaping groups and reducing its workload by setting an impossibly high bar for smaller e-cigarette and e-liquid companies, but in doing so it will perpetuate smoking.

Until you fix the incentives nothing will be done. Looks like Vaping will go up in smoke unless Congress changes things.

It will just be driven to the black market products that were actually causing the problems. Another brilliant move.

Brilliant in the sense that the continuing problems with the black market products will provide perpetual excuses to keep them outlawed, yes. See: Drug War.

These are 2 pay checks $78367 and $87367. that i received in last 2 months. I am very happy that i can make thousands in my part time and now i am enjoying my life.GRj Everybody can do this and earn lots of dollars from home in very short time period. Your Success is one step away Click Below Webpage…..

Just visit this website now............ VISIT HERE

Isn't the incentive "to not die early from lung cancer'" enough to keep the people who ought to stay in the gene pool from smoking?

No. Just like the incentives to not die from an overdose or go to prison are insufficient to keep people from abusing drugs, and the incentive to not die from cirrhosis and ruin your life are insufficient to keep people from abusing alcohol.

So government is there to help by banning bad things. Yay government.

...by ineffectually banning bad things and making them worse.

"unless Congress changes things"

Congress made this mess in the first place.

Follow the science!

Since vaping has nothing at all to do with tobacco, prohibit it because tobacco can be dangerous.

After all, we must eliminate as many choices as possible as quickly as possible before those icky republicans undo all the elections "reforms" forced through during the "emergency" and maybe actually win an election of two next year.

From what I understand, the Nicotine used in Vaping products comes from tobacco. This was the justification the FDA used to call it a "tobacco product" and limit it. But since there are nicotine free vaping products, the question is what the FDA will try to claim allows them to regulate those.

They will claim feels

You can also extract nicotine from tomato potato and eggplant leaves (nightshade family). So technically they don’t have to be tobacco products

If the tank and heater are intended largely for nicotine-containing products, then, going analogously to how they regulate medical devices, the tank and heater are tobacco products. That makes vaping fluids, regardless of their contents, accessories to tobacco products, hence also tobacco products. At least that's how both the statutes and regs on medical devices are written and administered. Like sheet music for a lung flute.

It was in the article:

The law the agency is tasked with enforcing was passed in 2009, years before the unanticipated rise of e-cigarettes. Backed and negotiated by tobacco giant Philip Morris.

Regulatory Capture

Philip Morris is a private company selling a product people wish to buy voluntarily with their own money, so PM should be able to do what it wants without government interference.

QE libertarian D.

"Unintentionally"

I question this assertion.

Yeah I got a chuckle out of that too.

Maybe the tobacco tax revenues were down.

"The FDA Is Set To Unintentionally Push Quitters Back to Smoking"

Personally, I question whether the article title should have said have even bothered to say "unintentionally"

Most things government accomplishes are "unintentional" because there's no upside for bureaucrats and very little for politicians in thinking through to the actual consequences of their policies. If a businessman sold products that did the opposite of what he sold them for, he'd soon be out of business, but the two major parties keep getting reelected no matter how often their policies work in reverse.

Progressives care most about how things look; they must be seen to help, and whether people are being helped or harmed is of secondary importance. It's all about the optics.

Vaping looks like smoking. That explains everything.

Actually vaping looks much worse than smoking. Just look how *much* smoke there is!

It's an illusion caused by the drug-like components.

There's actually no smoke at all.

The same can be said about guns.

That's home made products and devices. And the videos make sure they get great shots of all that vape coming at you. OTC products like Juul produce nowhere near that much vape.

No one likes a quitter.

Which are...what?

It's a serious mistake to concede this question. If you believe use of nicotine by "youth" to be harmless, as I do, say so. Don't concede that it's harmful just because there could be hypothetic overdosing if it's to the same degree that children could, for instance, get too much exercise, drink too much water, or hurt their genitals by masturbating with rough objects.

I've made it up to a P60 grit with my masturbatory sandpaper. Just gotta work up a good callous.

36 is next!

If anyone trusts the FDA not to fuck up something, especially after the past 18 months, they’re an idiot.

The anti-smoking groups actually want people to smoke because their careers depend on them. Smokers are also easy to identify and stigmatize.

It's true, everyone feels good about getting to sneer at niccers.

The agency has already rejected 4.5 million applications from a single company

Emphasis added. WTF?

I know, right? "Who" else but a 'bot could submit that many? What else but a 'bot could review them?

As noted the Trump administration was arguing against these bans. Biden is full speed ahead. Once again Reason gets what they wanted and then bitches about it. Sad.

Helps their bottom line. They aren’t libertarian. They are a business.

Excellent article Jacob.

In a nutshell, Big Pharma and Big Tobacco teamed up with anti tobacco extremists to impose enormous and costly regulations for all modern smokefree tobacco/nicotine alternatives that are 99% less harmful than Big Tobacco's cigarettes and more effective for smoking cessation than Big Pharma's Nicorette/Nicoderm and safer than Big Pharma's Chantix.

Even worse than the 2009 Tobacco Control Act was the 2014 FDA Deeming Regulation (that was lobbied for by Big Tobacco, Big Pharma, anti tobacco extremists, and the signers of the new article urging FDA to support vaping) that (when implemented next week) will ban >99% of nicotine vapor products now on the US market, and creates a monopoly/oligopoly for the future US nicotine vapor industry that will likely be controlled by the worlds largest cigarette manufacturers (Altria, PMI, BAT/Reynolds, Imperial Tobacco, JTI).

You’re a good person, but you lack facts.

There is no evidence that vaping is less harmful than electronic cigarettes or that those are less harmful than cigarettes and cigars.

All the studies purporting to prove it are based in animals or simulations.

You’re talking bull.

You are completely ignorant of real science. Yes, Vaping is safer.

All the studies purporting to prove it are based in animals or simulations.

So until you see a human study showing that it's a bad idea to eat radioactive, you're convinced it's safe to eat it? No evidence it's not, right?

FDA has the authority for this WHERE in the Constitution??????????

Right there in Amendment 15.5: FYTW

The general welfare clause, of course.

Excessive regulation is generally a welfare of contributions to politicians.

If there's something fishy going on in the drugs market, it's just another day.

You know what's interesting? Merck, manufacturer of a popular brand of Ivermectin, got its start in opium and cocaine. Funny how these things got outlawed only after global wealth empires were established on them.

Industry did more than ignore science, it warped it to its ends. I grew up being told the lie that dietary fat was bad and bowls full of sugar were good.

Obviously the solution for more accurate science is to just get government out of the way.

It's silly to think vaping will be a gateway to smoking. Humans like their nicotine addictions. We might as well figure out the least unhealthy ways to provide it.

Besides, what are children supposed to do after a long day of being hopped up on adderall? Not smoke something?

The same can be said about guns.

The drastic drop in cigarette smoking over the past few decades is one of the great public health victories in my lifetime.

Most people who have failed to quit by other methods are able to switch to vape which is much safer.

And the government will find a way to screw it up.

No evidence it’s safer.

Yes, there is evidence, you're just ignorant .

Smoking is bad for your health, everyone knows it except them. I wonder why?

Thank you for sharing this content Projectgate

A shocking with the value more than 400,000 of them die prematurely every year. There should be effective ways and is a great need to educate them regarding adverse results.

We provide unique service in the field of the used car selling or buying. We provide a platform on which the buyer and seller of the car easily deal with each other. We provide satisfactory service for the dealer and buyer. please check used cars like proton iswara with reasonable prices and contact the dealer for more detail. Also, visit our site for checking many other models of the car. We provide unique service from others in malaysia.

we provide best service for buying and selling used cars at one platform which is lepaskunci.com.my

See the documentary "I Billions Lives" to get a good handle on how much safer vaping is than smoking.

Drugs are seriously a curse of society.

Serious steps should be taken to decline the rate of effects.

Guess I better stock up...

I doubt the motivation has anything to do with health, and everything to do with cigarette taxes. If people aren't smoking, that tax revenue stream disappears.

Motivate them

The simple solution is to ban flavored nicotine products. If you want nicotine you will have to settle on an unflavored product. If kids want to vape flavored products they at least won't get addicted and adults who are already addicted can still get their fix, just not candy flavored.

If the FDA now knows that their actions will drive people back to smoldering tobacco, then it is not unintentional. They're in the business of power, and every once in a while they protect the public.