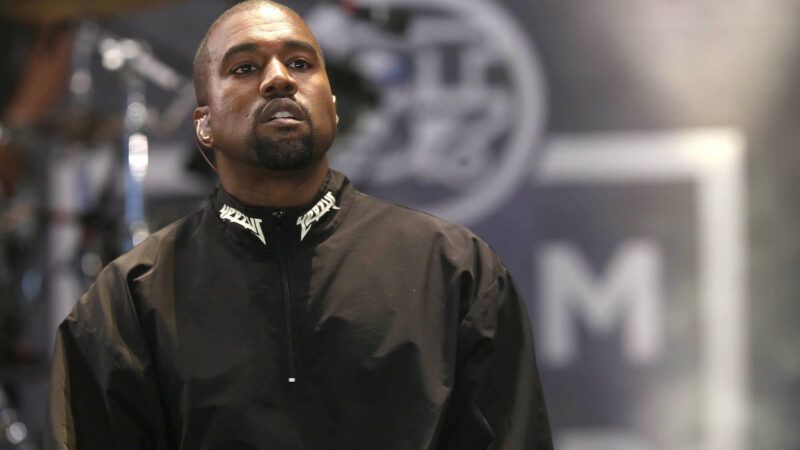

Donda Is a Portal Into Kanye West's Exquisite Mania

He may have taken off the MAGA cap. But he's still finding a way to push people's buttons.

Over the last five years, Kanye West has met Donald Trump, flirted with MAGA-ism, gotten divorced from Kim Kardashian West, re-devoted his life to Christianity, produced an award-winning gospel album, and run for president (receiving roughly 60,000 votes). Though West has taken off the red cap, he's still finding new ways to press people's buttons, daring fans to keep liking his music, no matter how he presents himself.

West began his public life as an innovative music producer and rapper, but has since morphed into something grander and weirder—part pop star, part fashion mogul, part social media maniac, part eternal thinkpiece subject. No other contemporary pop star courts controversy quite like Kanye West. Whether by design or by accident, something is always going on with West, and whatever it is, it's usually too much. It's also almost always fascinating.

At times, real-life antics have threatened to overtake the music, but for the last year, the antics and the music have become conjoined. At the end of July, West finally set a release date for Donda, an album he'd been teasing for more than a year.

After a scattered period that included Ye, a brief album that debuted to decidedly mixed reviews, the title alone seemed to promise a return to West's musical roots: It was named after his mother, Donda C. West, who died in 2007. West rose to fame on the strength of both his behind-the-beats production savvy and his heart-on-the-sleeve intimacy; Donda looked like an opportunity to revisit both.

Before the album's official release, however, he planned a show—a livestreamed event in which he simply played the album for a crowd. The resulting performance, in which Kanye wore netting to obscure his face and strolled around a blank, starkly lit Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Georgia, was one of the strangest and most striking mass-audience musical events in recent memory.

Even stranger, in some ways, was that the promised album did not materialize the next day, on its scheduled release date. Instead, West announced another show, and another release date. The version of Donda he'd played had its moments but sounded decidedly unfinished. West indicated he was still working on it, supposedly from his cell-like quarters inside the stadium itself.

For West, this was par for the course; he's delayed or failed to produce albums before. When it comes to records, he's a famous procrastinator, always tweaking and revising right up to the last minute, and sometimes even making post-release changes, as on his 2016 album The Life of Pablo, which West edited on streaming services after it came out.

So it wasn't all that surprising that Donda didn't materialize after the first live performance—or the second one, in which West replicated the sparse bed-and-boots layout of his stadium quarters in the middle of the field, surrounded himself with dancers, and, in the final moments, launched himself through the sky.

The show, like the first one, was idiosyncratic in the extreme, a magnetically bizarre spectacle that became one of Apple's most-watched livestreams ever. It was mesmerizing—part goofy performance art piece, part soul-baring musical demo reel.

Later in the month, West scheduled yet another live stadium performance, this time in his hometown of Chicago where he had a replica of his childhood home built in the middle of the field. At the end of the show, which was again watched by millions, he appeared with shock rocker Marilyn Manson, who is facing several lawsuits for alleged sexual assaults, and rapper DaBaby.

The latter was recently booted from a string of festival performances following after video emerged that he'd been shouting "If you didn't show up today with HIV, AIDS, any of them deadly sexually transmitted diseases that'll make you die in two, three weeks, then put your cellphone light up," at a Miami music festival. But both Manson and DaBaby ended up appearing on the record. Was West making some sort of oblique statement by partnering with these figures? Did he just like associating with controversial people? Was this the 2021 music-world equivalent of donning the MAGA cap? Or was there something more?

The day after the third show, the album once again failed to materialize. And it began to seem as if it might never come out, that it might exist only as a series of temporary installations seen at fantastically odd stadium performances and livestream recordings of questionable legality passed around by fans. The performances of the album might be what Donda actually was.

West was Truman Show-ing himself, presenting himself as a guileless not-quite everyman, a weirdo in an elaborate bubble living his life for our entertainment and amusement. How could the album ever be released, let alone finished? Kanye West, the person, never was.

When Donda finally hit streaming services last Sunday, West immediately claimed that the studio had released the album without his permission. One of the album's tracks disappeared, then reappeared the following morning. Even in release, the album wasn't finished. With Kanye West, nothing ever is.

But maybe that's the point.

What's there for us to listen to now is just as fascinating and weird as the process that led to its release—a sprawling, ambitious, intimate, epic sketchbook of an album. Clocking in at more than two dozen songs and over 100 minutes long, it's overstuffed and somewhat under-developed yet packed with moments of exuberant revelation. It synthesizes musical elements from the gospel tradition, classic soul, film scores, scuzzy trap-rap, industrial metal, and radio-pop. As always with West, it's entirely too much—and also fascinating.

The album opens with a repeated incantation of the word "Donda," then proceeds to a grand opening number, the stadium-rock anthem "Jail," in which West offers the half-hearted contradiction, "I'll be honest, we all liars." The song ends with a guest verse by fellow rap royalty and recurring West collaborator Jay-Z. The guest verse looks back not only on their work together, grandiosely comparing the duo to Moses and Jesus but on West's political flirtations. "Told him, "Stop all of that red cap, we goin' home," Jay-Z raps, before moving on to complaining about thinkpieces.

It's funny, on-the-nose, vainglorious, self-referential, and self-aware without being self-critical, which makes it a fitting frame for the rest of the record. Despite the name and the evocative stadium setpiece, Donda, it turns out, isn't a deep-dive into West's history. Although the album draws from his past, it's not a memoir or a story of self-creation. West isn't reflecting on himself so much as simply being himself.

The ecstatic musical highs are still there—anyone who has ever enjoyed a Kanye West record will find some beat, some chorus, some expertly twisted synth hook to appreciate—and the messy, unfinished nature of the record makes it feel even more personal and more appropriate. West may not have finished the album to his liking, but like him, it's out there, in all its shaggy, half-genius glory for all of us to experience and argue about.

With its epic running time and its not-quite-complete feel, Donda is a pure reflection of the artist; it's a little like getting a glimpse into Kanye West's musical diary. In that way, at least, it lives up to the implied promise of the title. Donda is a journey into Kanye West's exquisitely tortured psyche. West has done what only the most powerful pop stars ever manage to do: He's brought us into his mania. The man, the music, the antics, and the experience of watching him live and listening to his music have fused. Donda is too much in every way. But for Kanye West, too much is barely enough.

Show Comments (23)