Key Medicare Fund Will Be Insolvent in Just Five Years

The health program won't be able to pay all of its bills starting in 2026, according to a new Trustees report.

Five years.

That's how long until Medicare officially can't pay all of its bills, according to the latest report on the program's fiscal health. After that, without changes, the program will start to miss payments. Medicare is on track for a serious fiscal meltdown.

First, the gory details: Starting in 2026, the program's Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund, which covers a variety of inpatient hospital services, will be depleted, leaving the fund to operate on a cash-flow basis—and there won't be enough cash coming into the program to pay all of the bills. Instead, the program will be able to pay about 91 percent of its tab, Medicare's Trustees estimate. Without changes to the program's financing structure, that percentage will shrink, leaving Medicare able to cover a smaller and smaller share of the costs associated with the HI fund.

Medicare already pays less than private insurance in many cases, and it's a major payer for most hospitals. A nearly 10 percent reduction in payments would prove financially devastating to some hospitals, especially those that serve poorer populations, many of which are already struggling to stay afloat.

No doubt, this will result in some policymakers suggesting that Medicare should be restructured so that it can draw from general revenues, like the program's Supplemental Medicare Insurance (SMI) fund, which pays for outpatient care, physician services, and prescription drug benefits. As the Trustees report notes, the SMI fund is "adequately financed into the indefinite future because current law provides financing from general revenues."

Essentially, this means it has an unlimited claim on federal funds. And that, in turn, means that it will extract more and more from taxpayers—or, as the Trustees report puts it: Due to "the rapid growth of its costs, SMI will place steadily increasing demands on both taxpayers and beneficiaries."

The problem, in other words, isn't the particular financing mechanism. It's runaway spending growth and the health program's underlying structure, which does little to meaningfully control costs.

Looked at one way, Medicare's looming insolvency is hardly news. The program has been fiscally shaky for years now, and last year's Trustees report similarly projected that the HI fund would be depleted in 2026. This year's report just reiterates that the fund is still set to run out of money well before the end of the decade.

At the same time, the fact that it's not news is itself notable. This is something the political class should be talking about. But they're not.

We've now made it through the 2020 presidential election, which means we are one presidential election away from one of Medicare's key funds becoming insolvent. The next president is going to have to deal with this.

And yet, unless you're the sort of person who watches budget committee hearings and reads reports about entitlement financing, you've probably heard very little about the shortfall. Certainly, it's hardly been an issue in national politics.

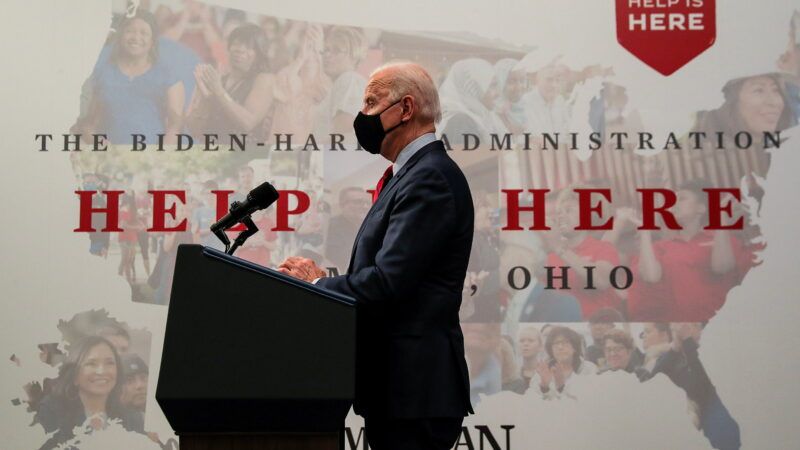

If anything, both of the last two presidents have promised to not solve Medicare's fiscal problems. Former President Donald Trump repeatedly insisted that he wouldn't raise taxes or reduce spending on Medicare. President Joe Biden, meanwhile, has proposed a substantial expansion of Medicare, adding an array of new benefits as part of the $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation plan now working its way through Congress. Needless to say, Biden's plan to expand Medicare would not fix its looming fiscal woes.

Indeed, it is notable how little attention has been paid to entitlement financing in recent years. Under President Barack Obama, at least, the interaction between entitlement financing and federal debt and deficits was a live issue. Since total federal debt is essentially a product of annual deficits, and the deficit is merely a measure of the gap between tax revenues and spending, the commissions tended to recommend some combination of tax revenue increases and spending reductions. Tax rates might have to be raised. Entitlements might have to be trimmed.

Naturally, none of this ever happened.

And now a major health care entitlement is on track to effectively trim itself in less time than it takes George R.R. Martin to write a book. For Medicare, winter is coming.

Show Comments (65)