We Will Keep Spending Trillions on the Afghanistan War Long After the Last Soldier Leaves

The final price tag could eventually exceed $6 trillion, and American taxpayers will be paying the tab when the 50th anniversary of 9/11 arrives.

We may finally be nearing the end of America's long military misadventure in Afghanistan—but we are a long way from being done paying for it.

The post-9/11 wars begun by President George W. Bush and carried on by three subsequent administrations were largely financed by adding the cost to America's national debt. That means that the official cost of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—about $2.26 trillion, though the Pentagon's accounting is famously fuzzy—doesn't tell the whole story.

"The costs of these wars continue long after we withdraw, since they are debt-financed and we will be paying interest on that debt for years—even decades—to come," Heidi Peltier, project director for the Costs of War Project at Boston University, tells Reason.

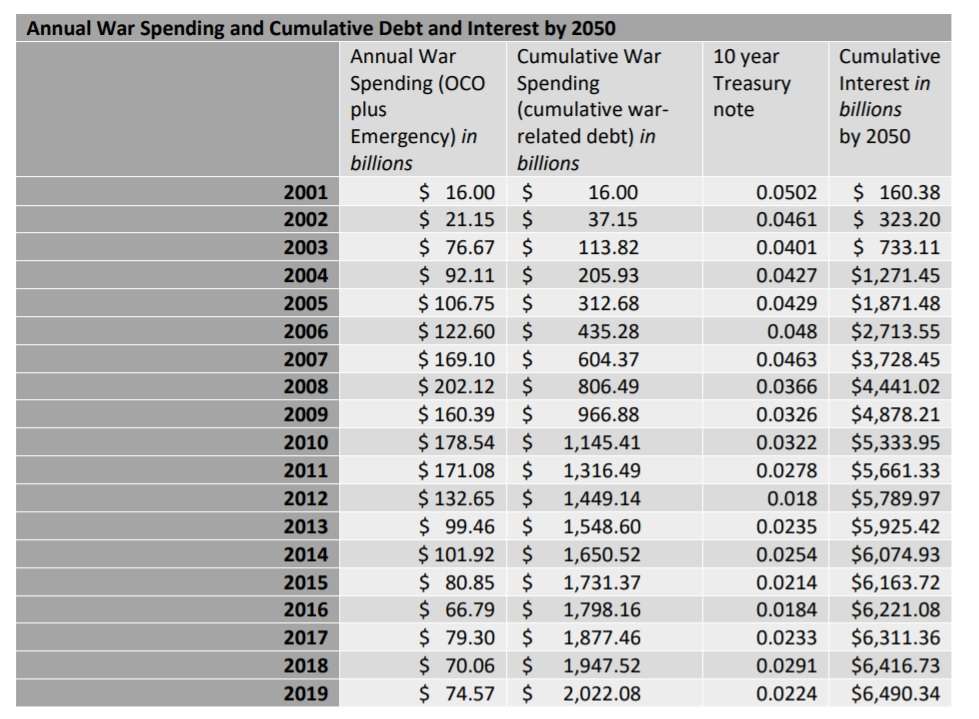

Peltier's research shows that the interest costs of the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq had already topped $1 trillion. By the end of the current decade, interest on the war debt will likely exceed the final official tally of the wars' cost. And the final price tag for those operations could eventually exceed $6 trillion—with American taxpayers still paying the tab when the 50th anniversary of 9/11 arrives.

Of course, the fiscal costs are only part of the whole story. An accurate accounting of the war in Afghanistan must take into account the roughly 2,400 American service members, 3,800 American contractors, 66,000 Afghan security forces, 47,000 Afghan civilians, and others (including journalists and aid workers) who were killed. In all, the Costs of War Project estimates that at least 238,000 people died as a result of the war in Afghanistan.

There will also be ongoing costs to cover the medical treatment for the four million veterans of the two post-9/11 wars, many of whom are injured or disabled. Those obligations will eventually total $2 trillion, according to an estimate from Linda Bilmes, a researcher at Harvard University's Kennedy School and a longtime critic of the official estimates of the wars' cost.

"Uncle Sam has spent more keeping the Taliban at bay than the net worths of Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and the 30 richest billionaires in America, combined," notes Forbes' Christopher Helman and Hank Tucker.

Never before has America faced the prospect of paying off a decades-long debt-financed war. In her 2020 paper, Peltier points out that previous American wars have been primarily financed with tax hikes and war bonds—

a form of debt, but one that Americans voluntarily bought into, rather than having forced upon them. About half the cost of World War II was covered by regular tax revenue, and nearly the full cost of the Korean War was as well.

But rather than raising taxes or shifting budget priorities to pay for the post-9/11 wars, Congress has done the exact opposite. Taxes have been cut, twice, since the war in Afghanistan began, and government spending on non-war items has skyrocketed. The national debt totaled $5.8 trillion in 2001. Now, it exceeds $28 trillion.

Interest costs on the debt—at least some of which are attributable to the 20 years of "credit card war"—is the fastest-growing portion of the federal budget, and it won't slow down anytime soon. By 2050, the cost to service national debt will be the single largest line item in the federal budget.

The federal government might assume that it has an endless supply of borrowed money to spend. That's probably not true—but even if it is, every dollar that must be spent over the next three decades to pay off a failed war from the past is a dollar that can't be used for some other purpose.

"By paying for these wars through debt rather than increased taxes, the costs get pushed to future generations of taxpayers—either through increased future taxes or from cuts to other types of federal spending," Peltier tells Reason. "Interest costs will increasingly crowd out opportunities to spend federal dollars on other programs and even ultimately on the military itself."

The war in Afghanistan is (hopefully) over. But the bills are only starting to come due.

Show Comments (97)