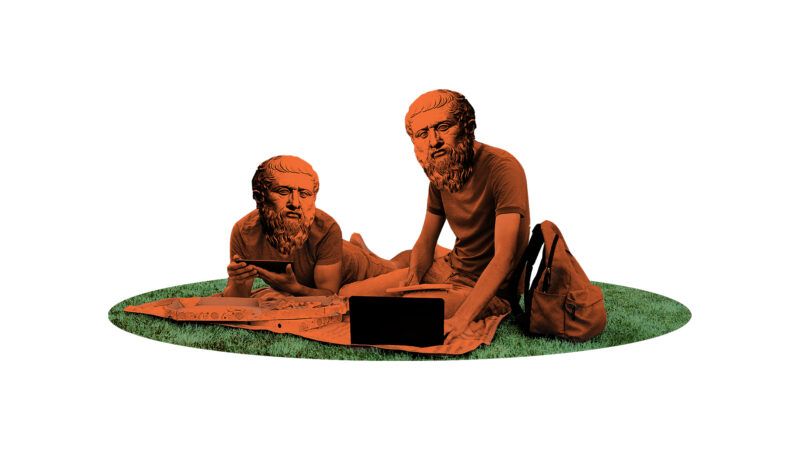

If Class Outside Was Good Enough for Plato, It's Good Enough in a Pandemic

Virtual or masked classes are barriers to learning, not just disease.

The 1960s TV spy spoof Get Smart had a ridiculously unworkable piece of conferencing hardware called "the cone of silence." Unfortunately, that gives a pretty good idea of what's been happening in the pandemic-era college classroom, with its Zoom classes and its in-person classes held behind plexiglass barriers and mandated masks. These efforts to block viral transmission are blocking voices, hiding facial cues, and making the quieter students retreat even further.

Imagine if the makers of buggy whips had responded to the automobile's advent as colleges have dealt with the pandemic: "Try our new virtual whip, the Invisi-Smack—or upgrade to the Wonderwhip2000 whose extra-thick grip kills germs while spurring steeds to higher speeds."

That's not a compelling product; nor, these days, is an American college. By moving online and trying to retrofit classrooms for social distancing, colleges are building barriers between the school's two essential groups: teachers and students. The institutions are acting like their value proposition is the classroom when it's actually the learning that students get from teachers and from each other.

Certainly, we should all wear masks when we must be indoors. But here's the thing: We don't have to be indoors. Outdoors is where Plato taught, and it's where I taught. He used an olive grove outside of Athens; I used the central quadrangle, the Quad, at James Madison University (JMU) in Harrisonburg, Virginia.

A recent Swedish study found increased levels of engagement, motivation, and achievement with outdoor learning. American colleges already have plenty of grass and trees, and they've long been paying lip service to outdoor classes (as a glance at their promotional videos would indicate). But now it's time to put these campuses into the service of learning.

My students earned better grades last year than ever before, and the ones who showed up in person scored a letter grade higher on average than the ones who took advantage of my Zoom simulcast. Other students would approach me on the JMU Quad and express a wish that their professor would teach outside. One such student wrote an op-ed for the campus paper with the headline "Hold more classes outside."

Unfortunately, many professors routinely dismiss outdoor teaching by claiming "it's too hot" or "it's too cold." When we had classes in 90-degree heat, we'd sit under a tree and sip ice water. I took some hints from Susan Hrach's new book Minding Bodies: How Physical Space, Sensation, and Movement Affect Learning. She urges professors to stop treating college students as mere "brains on sticks." So when it was cold, I kept the class short and kept students moving with a motion-oriented workshop.

Did you notice the word "workshop"? Teaching outside means the instructor should develop a workshop, or at least a vibrant discussion, for practically every class. That gets to what might be the hardest part about teaching outside: Teaching outside works best after "flipping" a class away from lectures and into a seminar.

A seminar is based on outside reading. It's what they do at Oxford, Cambridge, and in upper-level American courses (though they're called "tutorials" across the pond). The seminar treats college students like adults, while a lecture presumes students are too lazy to read material in advance. The seminar frees up precious classroom time for discussions, guest speakers, and those aforementioned workshops.

"It almost doesn't feel like a class," exclaimed one of my students. "It's kind of this fun learning experience, which is why I think I benefit greatly from it."

My students often did not want to leave when class ended. Why would they? Zoom burn-out is real. And for many students, mine was their only in-person class; so they tended to linger in small groups even after the bell rang.

"I like this class," one student told the campus TV station, "because it gives me more of an opportunity to be with other people."

America has a history of outdoor education, but it's confined primarily to K-12 schools, some of which are devoted to learning outside. During this pandemic, however, we've seen many restaurants move outside. Some colleges put up tents, but there were none at JMU—and even where they were readily available, they seemed rarely used by professors, who are typically given wide latitude in the configuration of their courses. Why so many fair-weather faculty? The ones that I've asked keep talking about the weather. But I would remind them that current science says the safest way to hold in-person classes is outside.

Speaking of science, I must admit that moving a chemistry lab's Bunsen burners outside during, say, an icy day in Minnesota may be beyond my Platonic dream, but you never know. After all, my class did fire up a propane camp stove on the JMU Quad last February (though I must confess that it was for a pancake breakfast). Others have asked if my plan would necessitate the end of enormous freshman lectures. Probably, but would that be such a bad thing? A star professor with a 200-person class could be videotaped in advance. Students could then meet outside in small groups with a professor or teaching assistant.

Here in Virginia, the total annual bill for an in-state student to attend a residential public university can top $30,000. Private colleges can be double this amount. With such price tags, it's unsurprising that the university system was under fire even before the pandemic. But making classes virtual has emboldened critics to suggest that colleges are hardly better than the videos students can find on YouTube, Coursera, or LinkedIn. It's also no surprise that undergraduate enrollment in America fell by a record 5 percent last year.

Many students and professors, faced with the pandemic's virulent delta variant, are understandably resisting their college's call to go indoors and risk infection. My advice is simple: Stay outside. It worked for Plato.

Show Comments (56)