The Senate's Infrastructure Bill Redefines 'Broadband' To Manufacture a Connectivity Crisis

It is the equivalent of mandating that all new homes come with at least five bathrooms.

The $1 trillion infrastructure bill that the Senate approved in a bipartisan fashion on Tuesday morning includes a provision to redefine "broadband" internet in a way that could leave many American households with seemingly inadequate online access. What is more, the bill relies on those same dubious new definitions to direct billions of dollars in new government spending.

Tucked inside the 2,700-plus page bill is a new set of definitions for upload and download speeds that federal regulators will use to determine which parts of the country are "underserved" by broadband internet. In turn, those updated definitions will guide the distribution of $42 billion in federal grants that the bill authorizes for "deploying broadband, closing the digital divide, and enhancing economic growth and job creation."

The bill, which cleared the Senate with 69 affirmative votes on Tuesday, classifies a household as "underserved" if it does not have access to a connection with download speeds of at least 100 megabits per second and upload speeds of at least 20 megabits per second. As Reason has previously explained, that's a significant change in the government's standard for satisfactory internet speeds: under current rules maintained by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), a broadband connection is defined as having speeds of at least 25 megabits per second and upload speeds of at least three megabits per second.

Under the current definition, the FCC estimates that there were about 14.5 million Americans who lacked access to broadband internet at the end of 2019. But that number has been falling rapidly—it decreased by about 20 percent during 2019 alone, according to an FCC update published in January of this year. The so-called "digital divide" is still a problem, but it is an increasingly narrow one. The infrastructure bill will effectively widen it.

The definition of "broadband" has changed several times as technology and consumers' demand for internet services have increased. The current "25/3" standard has existed only since 2015. The first standard, in place from 1996 through 2010, required at least 200 kilobits per second upload and download speeds. From 2010 through 2015, that was upped to 4 megabits per second for downloads and 1 megabit per second for uploads.

What's different about this latest change, however, is that the new standards far exceed the needs of most residential internet users. It's important to remember that the standards for "broadband" are not a ceiling for what providers offer but rather a floor for what the government considers essential for all Americans. Households that want a 100/25 connection (where those are available) are free to pay for higher-end online access.

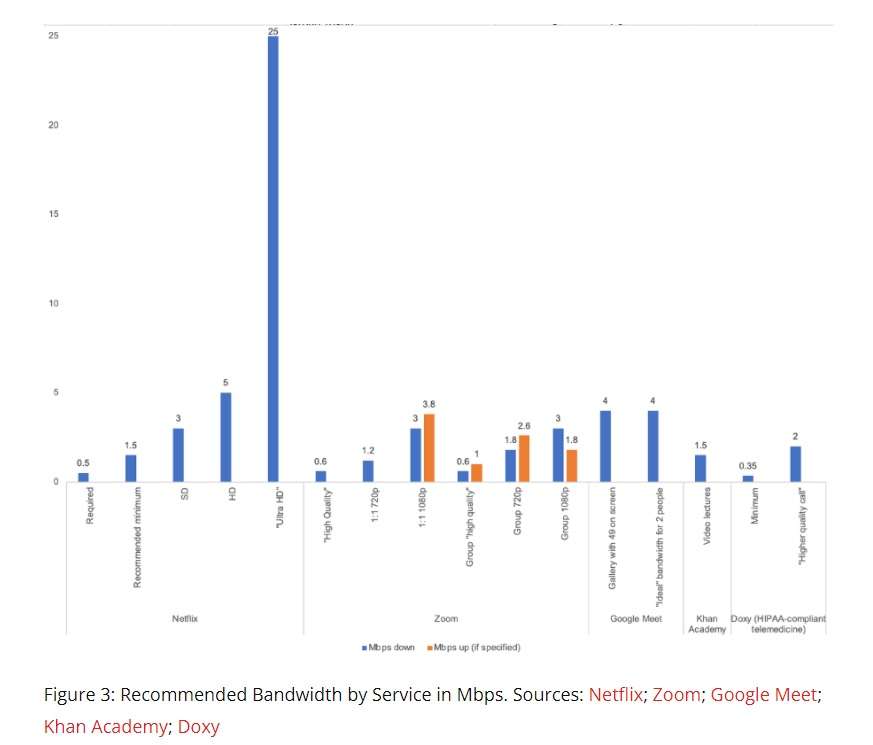

How much internet speed do you need? An average Zoom call, one of the most upload-heavy common online activities (because the vast majority of online traffic is downloaded), uses a mere 1 megabit per second. As this helpful graphic from the Technology Policy Institute demonstrates, a "100/25" connection is wildly out of sync with what most online services recommend:

When The Wall Street Journal and researchers at Princeton University and the University of Chicago teamed up last year to study the internet use of 53 Journal staffers—people who likely use the internet more heavily than most Americans—they found that users with connections capable of 100 megabit download speeds used, on average, 7.1 megabits per second of their capacity.

In other words, the new federal broadband rule is the equivalent of mandating that all homes have at least five bathrooms. Sure, there are some households that might need that, but it's silly to enforce such a sweeping standard on everyone.

Silly, that is, unless you're in the business of building bathrooms—or providing high-speed internet connections. The proper way to understand the new definition of "broadband" is as a huge government-created bonus for internet service providers who offer cable and fiber optic connections. Those are pretty much the only ways to achieve the hyper-fast download speeds that would qualify as "broadband" under this new definition.

Those providers have faced increasing competition in recent years from mobile networks and satellite internet providers, which can offer comparable speeds at lower costs because they can beam internet to households instead of having to lay physical lines. But redefining "broadband" to only include higher speeds means that some of those services will now appear to be subpar based on government standards, even though nothing about their service has changed.

More importantly, it also means that only some internet providers will be eligible for the massive amount of broadband subsidies that are about to start flowing out of Washington in order to bring those supposedly "underserved" American households up to speed.

Ironically, the change in definition might actually make it harder to close the so-called "digital divide." As Joan Marsh, a vice president at AT&T, pointed out in March when the present debate over broadband definitions was first ramping up, setting poor standards can result in "overbuilding" that prioritizes faster access for places with already-fast connections rather than reaching the hard-to-connect parts of the country. "Accurately defining unserved locations is essential to efficiently targeting subsidy dollars to those areas most in need of connectivity, including sparsely populated areas where there are currently no fixed broadband solutions at all," she wrote.

Sure, AT&T has a major stake in this fight—as a wireless provider of internet service, it is in ongoing competition with the cable and fiber optic providers in the market—but that doesn't make this objection any less relevant. If the government's goal is to get all Americans online access, any connection should be viewed as superior to no connection.

Instead, the new definitions in the infrastructure bill will encourage subsidies to flow towards companies that promise to get already-connected Americans even faster connections—at speeds they aren't demanding and probably won't use—rather than extending access to those who still lack it.

Show Comments (76)