Democrats' $3.5 Trillion Fully-Paid-for Spending Plan Probably Won't Be Fully Paid for

The spending proposal is likely to be offset by gimmicks and rosy assumptions.

Yesterday, Democrats on the Senate Budget Committee released the outline of a $3.5 trillion budget agreement. That's $3.5 trillion in addition to the $2 trillion or so already spent at the beginning of the year on the recovery plan, and beyond the roughly $4 trillion spent last year on pandemic relief. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.), of course, was disappointed: He'd been pushing for $6 trillion in new spending. Ah, well.

Those previous plans were all deficit financed. But although many of the details weren't yet clear—the announcement was of a general framework and a top-line number—reports suggested that this plan would, somehow, be fully paid for, if only in the Washington sense.

Consider what it means for something to be fully paid for. If I claimed that I had fully paid for my cocktail bar tab, for example, you would probably assume that I had forked over actual money equivalent to the entire tab. Cocktails in. Money out. A more or less straightforward exchange of currency for services.

But for Senate Democrats, it probably means something more like producing an estimate showing that, over the next decade or so, drinking cocktails at this particular bar could generate enough money-making ideas to offset the cost of the drinks…maybe minus food items. The cocktails pay for themselves!

That's perhaps somewhat exaggerated. But it's not entirely off base. For decades, Democrats have lampooned similar logic when applied to tax cuts, opposing the GOP-endorsed supply-side logic that tax cuts "pay for themselves" by increasing economic activity and bringing in greater revenue in the long run. Those supply-side effects are real, but they are typically much smaller than the most enthusiastic partisans have hoped; rarely do they fully offset the revenue loss. (That's not necessarily an argument against tax cuts. It is, however, an argument against assuming that budgets will balance after tax reductions without commensurate spending reductions.)

Yet earlier this week, Axios reported that Democrats were likely to use dynamic scoring to offset the price tag of some of the new spending. Only instead of applying it to tax cuts, they'll be applying it to new spending programs—the assumption being that the new "programs will be so beneficial for the economy, they'll produce future tax windfalls." In the private sector, the saying goes that you have to spend money to make money. In government, you have to spend money…to spend money.

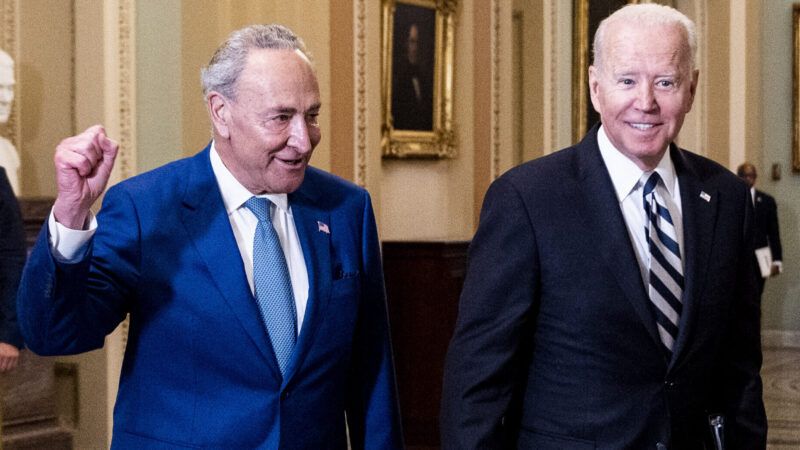

There are other gimmicks in the works as well, like providing temporary funding for programs that are expected to become permanent. The recovery package passed earlier this year, for example, included $100 billion for an expanded child tax credit. The expansion was initially set to last just one year. After that passed, President Joe Biden proposed extending that program to 2025, an expensive proposition. But reports indicate Senate Democrats may shorten that extension, providing, say, one or two years of additional funding in the $3.5 trillion package they are now working on.

Yet they have no intention of actually letting that program ever expire. Reducing the length of some programs is merely a way of reducing the cost of the bill on paper. As The Washington Post reports, "Democrats are prepared to fight for their extension in future budget battles with Republicans." The temporary programs, and the spending to support them, must extend forever.

Speaking of forever, Senate Democrats are all proposing to expand Medicare, adding a suite of new coverage areas, such as dental and vision. It is at least possible that a final bill will also expand eligibility to everyone aged 60 and up (currently, normal eligibility starts at 65), although that particular decision will be up to the Senate Finance Committee.

In theory, this will all be fully financed somehow or another. But what does it mean to fully finance an expansion of a program that is already in dire financial straits? Medicare's hospital fund is already running a deficit, and will for the foreseeable future. This year's Trustees report is months late, but the most recent official look at its finances showed that the program would be insolvent by 2026—meaning there simply wouldn't be enough money to cover the expenses. The program's Trustees have practically begged for a substantial overhaul of its shoddy finances. Instead, Democrats are piling on expensive new benefits.

And then there is the IRS. Democrats hope to boost funding for the agency in order to close the "tax gap," bringing in more overall revenue in the process. It is quite likely that this plan will bring in far less revenue than Biden and Senate Democrats hope. But it will give the IRS more power and more resources to snoop on private financial information and make life unpleasant for many more Americans.

After Senate Democrats released their plan yesterday, the earnest and ever-helpful deficit hawks at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) released a statement detailing myriad ways that a fully-paid-for bill might end up not being fully paid for: by expanding the 10-year budget window that has long been used for congressional budgeting, for example, or relying on rosy revenue and cost estimates created by self-interested Democratic lawmakers rather than the more conventional, conservative estimates produced by the Congressional Budget Office. "Politicians," the statement said, "should not be making up their own estimates, choosing their own scorekeeper, incorporating fantasy growth assumptions, or relying on future promises to pay for their spending today." The folks at CRFB are good people, but I do wonder: Have they ever met any actual politicians?

The ever-so-slightly exasperated headline on the statement declared, "Fully Paid for Must Mean Fully Paid For." It probably won't.

Show Comments (112)