The Publication of the Pentagon Papers Still Sets an Example 50 Years Later

Whistleblowers and publishers are crucial for keeping government officials reasonably honest.

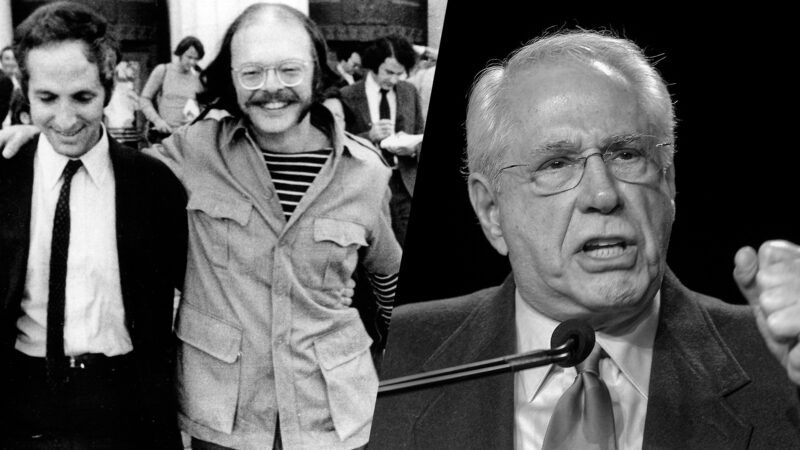

On June 27, U.S. military forces struck targets in Iraq and Syria "used by Iran-backed militia groups," according to the Department of Defense. Maybe that's the full story, and maybe it's not; we learned long ago to resist taking at face value the assurances of government mouthpieces. In fact, we were reminded of the need to question official stories when former Sen. Mike Gravel (D-Alaska), who helped to publicize the Pentagon Papers which revealed hidden details about the Vietnam War, passed away just a day before American bombs fell on the Iraq-Syria border region. And June 30 is the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision recognizing the right to publish those historic documents.

The targets bombed over the weekend "were selected because these facilities are utilized by Iran-backed militias that are engaged in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) attacks against U.S. personnel and facilities in Iraq," Pentagon Press Secretary John Kirby added. Assuming that Kirby is being completely candid about the attack, we might attribute his honesty to an awareness that this country's embarrassing military secrets have a history of leaking out and gaining public attention with a little help from those disgusted by official mendacity.

Gravel, who passed away on Saturday, was one of those who gave truth a helping hand when he had the opportunity. When Daniel Ellsberg leaked documents which came to be known as the Pentagon Papers that revealed greater and longer U.S. military involvement in Vietnam than was officially acknowledged, and an unspoken goal of containing communist China rather than defending South Vietnam, the U.S. government attempted to prevent their publication.

"Senator Gravel obtained a copy of the Pentagon Papers at the height of the Government's legal efforts to block The New York Times and other newspapers from continuing publication of their comments," The New York Times noted in 1972. "In an emotional midnight subcommittee hearing, the Senator tearfully read long passages into the official subcommittee record. He later arranged for them to be published by The Beacon Press, a nonprofit publishing division of the Unitarian Universalist Association."

Gravel entered the documents into the record on June 29, 1971, to make sure they were available for public consideration and debate. The next day—50 years ago, today—the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that The New York Times could continue to publish the Pentagon Papers.

The U.S. government subsequently went after Gravel and The Beacon Press, but the effort petered out with the eruption of the Watergate scandal. Meanwhile, the information in the published documents helped to shift public opinion against the Vietnam War.

The legacy of the Pentagon Papers, and of the exposure of official bullshit about government shenanigans, lingers decades later. In 2019, when The Washington Post reported on documents revealing "that senior U.S. officials failed to tell the truth about the war in Afghanistan throughout the 18-year campaign, making rosy pronouncements they knew to be false and hiding unmistakable evidence the war had become unwinnable," the newspaper labeled the report "The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War" in an echo of the Vietnam-era revelations. If officials couldn't resist the precedent set by previous high-level dishonesty, neither would leakers and journalists fail to follow in the footsteps of those who revealed earlier misdeeds.

But government officials who remain prone to conceal the truth also continue their resistance to exposure and criticism. Vietnam-era officeholders stumbled in their efforts to punish The New York Times, Mike Gravel, The Beacon Press, and Daniel Ellsberg, but their successors fight the same awful battles. Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, and Reality Winner are among the high-profile revealers of inconvenient secrets targeted in recent years by the powers-that-be. From one administration to the next, no matter which party is in power, officials try to plug (sometimes brutally) the release and publication of government information that threatens to embarrass officialdom in the eyes of the public. There's no reason to think such efforts will stop anytime soon.

"During the final days of the Trump administration, the attorney general used extraordinary measures to obtain subpoenas to secretly seize records of reporters at three leading U.S. news organizations," Fred Ryan, publisher of The Washington Post, pointed out earlier this month. "Unfortunately, new revelations suggest that the Biden Justice Department not only allowed these disturbing intrusions to continue — it intensified the government's attack on First Amendment rights before finally backing down in the face of reporting about its conduct."

"With the revelation that the Justice Department has secretly obtained phone and email records at multiple news organizations to sniff out the identities of journalists' sources, government employees who would otherwise come forward to reveal malfeasance are more likely to fear exposure and retaliation, and therefore to stay silent," Ryan added.

That, of course, is the whole point of targeting whistleblowers and journalists. Officials don't cherish the memory of the Pentagon Papers, or of any other exposures, before and since, of their misconduct.

Under pressure to change its ways, the Justice Department has promised to play nicer and that it "will not seek compulsory legal process in leak investigations to obtain source information from members of the news media doing their jobs." But, at this point in history, are we really about to start taking government pronouncements at face value? That would be an odd choice to make, 50 years after the Supreme Court ruled that the government couldn't prevent the publication of information contradicting official lies, and after subsequent decades of efforts to prevent new leaks of embarrassing truths.

So, take the Defense Department's spin on the airstrikes in Syria and Iraq with a grain of salt, as you should with every government pronouncement. To the extent that the spin is truthful, it's held to some degree of accuracy by officials' fears that their secrets will be leaked by insiders with a sense of decency, and then disseminated by journalists and publishers willing to risk the state's wrath. Fifty years later, the Pentagon Papers still cast a long shadow and remain an ongoing example for dealing with government misconduct.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Unfortunately the world hadn't yet been liberated from the censorious hellscape that was the United States of America before the passage of Section 230 of the otherwise-invalidated unconstitutional Communications Decency Act of 1996, so there were no pRiVAtE CoMPaNIeS to suppress the information at the behest of the government. It's good to be free!

I am creating an honest wage from home 1900 Dollars/week , that is wonderful, below a year gone i used to be unemployed during an atrocious economy. I convey God on a daily basis. I used to be endowed with these directions and currently it’s my duty to pay it forward and share it with everybody,

Here is where I started……….Visit Here

Making money online more than 15$ just by doing simple work from home. I have received $18376 last month. Its an easy and simple job to do and its earnings are much better than regular office job and even a little child can do this and earns money. Everybody must try this job by just use the info

on this page.....VISIT HERE

"Whistleblowers and publishers are crucial for keeping government officials reasonably honest."

Talk about the fox guarding the hen house! The days of "publishers" keeping government officials honest are long over. The purpose of the press, today, is to run interference for the Democratic party and the government. They push false narratives for the Democrats, and they work cover ups for the government, too.

Exhibit A: The subject of the Justice Department investigation that sought to seize the communications of four New York Times reporters appears to have been a memo from Obama Attorney General Loretta Lynch to Hillary Clinton, in which she promised Hillary Clinton not to let the investigation into Hillary Clinton's email servers go too far--and that's according to the New York Times itself.

"The identity of the four reporters who were targeted and the date range of the communications sought strongly suggested that it centered on classified information in an April 2017 article about how James B. Comey Jr., the former F.B.I. director, handled politically charged investigations during the 2016 presidential campaign.

The article included discussion of an email or memo by a Democratic operative that Russian hackers had stolen, but that was not among the tranche that intelligence officials say Russia provided to WikiLeaks for public disclosure as part of its hack-and-dump operation to manipulate the election.

The American government found out about the memo, which was said to express confidence that the attorney general at the time, Loretta Lynch, would not let an investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server go too far. Mr. Comey was said to worry that if Ms. Lynch made and announced the decision not to charge Ms. Clinton, Russia would put out the memo to make it seem illegitimate, leading to his unorthodox decision to announce that the F.B.I. was recommending against charges in the matter."

----New York Times, June 4, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/04/us/politics/times-reporter-emails-gag-order-trump-google.html

Withholding that memo was reprehensible behavior by the New York Times and their reporters--no matter what they published about the Vietnam War in 1971--especially in the face of an impeachment trial against Trump and all the crap the Times published on the subject of Hillary's email server, Loretta Lynch's handling of the case, Trump's alleged collaboration with the Russians, etc.

If the Times published story after story about Hillary Clinton and Comey's behavior at the FBI--and they just sat on that memo--why shouldn't we treat them as if they were working for the Democratic party and the Hillary Clinton campaign and running interference to cover for the FBI?

Much like with terrorists, rapists, murderers, and arsonists, the rights of the people in the press deserve our respect--no matter how horrible they are as people and no matter how disgusting their behavior. There's no good reason, however, to pretend that the press isn't made up of horrible people or that their behavior isn't disgusting. We're libertarians. We don't need a cute bunny on a poster to pretend that everyone who exercises their rights does so for the good of humanity. Yes, horrible people have rights, too, and they should be protected!

Whatever good will the press deserved for the Pentagon Papers and Watergate has been burned through and squandered long ago by their awful behavior since then. From all the polls I've seen, the press appears to be the most hated group of people in polite society today, and as far as I can tell, that hatred is well deserved. They should all be ashamed of themselves and their fellow journalists.

The reason journalism as a profession is imploding, with only a fraction of the journalists our economy employed 20 years ago, is that what they've been doing for our society isn't of much value to consumers. What we learn about the government's misbehavior today seems to be in spite of the press' efforts to hide it rather than because of the press publicizing it. The latest example is when the world's greatest virologists became so incensed by the government's and the press' misinformation campaign on the origin of covid-19 that they banded together to post open letters to the world--poking so many holes in the government's story and the media's narrative, both finally forced to capitulate to reality.

P.S. Journalists like Glenn Greenwald, Andrew Sullivan, and Matthew Yglesias are leaving "publishers" for Substack--I'm not sure traditional publishers can tolerate what they do anymore.

What do we know about the great debt the public owes to publishers for unearthing the truth about the government's misbehavior that Greenwald, Sullivan, and Yglesias don't know?

You type too damn fast. It takes me twenty minutes of hunting and pecking to put out my little diatribe while you cheerfully rattle off your treatise and I think that's unfair, I demand reparations. Or at least that your fingers be broken. But. yeah, good points.

Yes, but, what if I told you…Orange Man Bad!? Wouldn’t that excuse this behavior?

Ken,

shitty people deserve only contempt, and the past has little or no bearing on the present, particularly if the people are not the same. I am not arguing, I am amplifying your statements.

Maybe that's the full story, and maybe it's not; we learned long ago to resist taking at face value the assurances of government mouthpieces.

While you're at it, don't forget to resist taking the assurances of the press at face value as well. You might want to ask who exactly leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, why they leaked them, and why the New York Times decided to publish them. Would the hatred of Richard Nixon perhaps play some part in it by any chance? Is that why the documents were leaked, is that why they were published?

Remember Woodward and Bernstein and "Deep Throat"? Woodward and Bernstein knew damn well who Deep Throat was, would it have changed your perception of the reporting if you had known their confidential source was a disgruntled federal employee with a grudge against Nixon, somebody who hated Nixon? Did Woodward and Bernstein ever let on that their confidential source might have an ax to grind?

I mean, we know goddamn well that's how it worked with Trump because you can find that shit all over the internet these days. 50 years ago there was no internet and whatever sources of news you could find were invariably filtered through the New York Times. Do you think the New York Times only recently became partisan and biased or do you suspect they might have been partisan and biased all along but it's only recently that you've been able to see it?

The U.S. government subsequently went after Gravel and The Beacon Press, but the effort petered out with the eruption of the Watergate scandal.

Talk about convenient timing!

Well we could see they were partisan and biased back during Watergate. It was talked about a lot in areas outside the coastal US, but of course we get dismissed as flyover country. Unfortunately it infected a lot of state governments and newspapers as well once they were bought up by multinational corporations who are in bed with the big government surveillance mentality. So here we are with few people left who care enough and a far left nearly communist government with the tools to suppress anything they want in cooperation with amoral billionaires and trillion dollar corporations.

The only relief will be to remove left wing democrats from power permanently and end the security military surveillance state. But odds are long that can happen.

“Under pressure to change its ways, the Justice Department has promised to play nicer and that it "will not seek compulsory legal process in leak investigations to obtain source information from members of the news media doing their jobs.”

I’ll believe that when they drop the charges on Asange.

Or maybe when the NSA stops tapping people like Tucker Carlson's electronics

You've got to love the NSA's non-denial.

What is lacking today is the existence of a large number of "opposition press." During the Civil War, for example, there were many cities and towns in the North where both pro and anti Lincoln Administration papers existed. Except maybe for the WSJ and Orange Register, the vast number of papers today favor the Dems in power and castigate Repubs when they are in power. Even in 1964, there were major city papers that endorsed Goldwater. Were there any in 2020 that endorsed Trump? Until more (and more vigorous) opposition voices are heard in the mainstream press, then the NYT and WP will get away with any number of coverups, fake news reporting, tub thumping for fascism, and cheerleading for almost anyone with a (D) after their name.

It's nice to know there are still journalists out there who are so lacking in self-awareness that they can't resist patting themselves on the back. Too bad there's not a price on their heads.

Reason refuses to cover the illeGGal spying on the Trump camlaign and Transition, the political prosecutions of associates, or tge collusion between the DNC and the oligarchs to censor, deplatform, and bury information contrary to the ruling party's interests.

GFY with your old tales of whistleblowing. Blow them out of your own whistle

The Publication of the 2020 Election Fraud Still Sets an Example........... Oh whoops; Nope; those publications were censored and discredited by name-calling them conspiracy theories by Democratic Politicians.

Just to tell you how far we've fallen, the Steele Dossier is the "Pentagon Papers" of the 21st century.

The Panama Papers were a major piece of intel, but nothing to see, because, all the big US players seemed to have a (D) if I recall.

They are literally persecuting Asange for doing exactly what they did with the Pentagon Papers, and the media doesn’t care because Hillary Clinton was on the receiving end.

The media are hypocrites and traitors.

Copper-based Metal Powder

https://www.matexcel.com/category/products/metal/cu-based-metal-powder/

Copper alloys are dominant materials in the movement of mechanical watches.