Secret Recordings Reveal Officials Discussing 'Filthy' Conditions of 4,632 Immigrant Kids Held in Texas Tent Camp

In recordings and documents obtained by Reason, officials at the Fort Bliss tent camp admit that children lack basic necessities such as underwear and access to medical care.

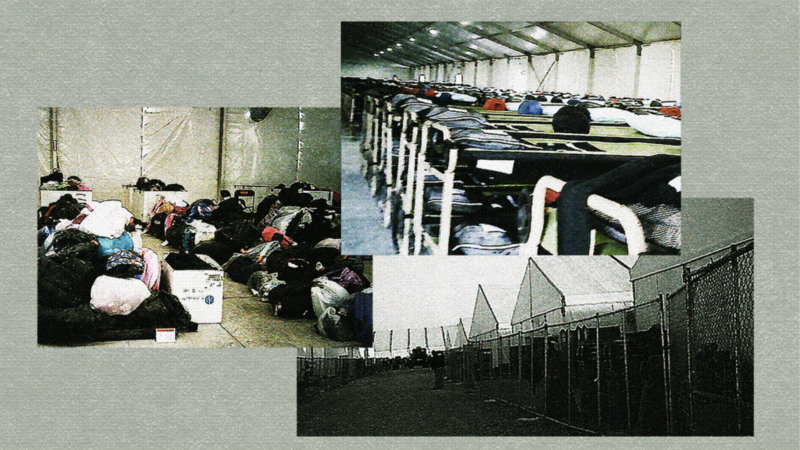

More than 4,500 immigrant children and teens are being held in enormous, filthy tents on a military base in Texas without access to basic necessities, including underwear, according to interviews, photos, documents, and recordings obtained by Reason. Hundreds of senior federal employees from various agencies have been detailed to the facility, where they are being highly compensated to perform tasks for which they have little training or direction.

"If you took a poll, probably about 98 percent of the federal workers here would say it's appalling," a federal employee detailed to the facility told Reason. "Everybody tries in their own way to quietly disobey and get things done, but it can be difficult."

The shelter, which is largely populated by teenage boys, is housed at Fort Bliss, an Army base near El Paso, where the harsh desert climate is used to simulate conditions in Afghanistan and Iraq. As other shelters are being shut down, the Fort Bliss shelter is swelling. In theory, these shelters are a way station for kids who are waiting to be reunited with relatives or other connections in the United States. In fact, staffing problems and other issues have left many kids stuck in limbo for up to a month or more.

The Associated Press first reported earlier this month that, after moving them out of Customs and Border Protection detention centers, the Biden administration is holding "tens of thousands of asylum-seeking children in an opaque network of some 200 facilities." On Monday, Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra said the Fort Bliss facility was not fit for "tender age" children, but thousands of teens continue to be housed there.

Recordings obtained by Reason reveal the stress the influx of unaccompanied minors has put on the federal government. They also reveal that leaders at the shelter are well aware that they are failing to provide basic necessities, including medical care and physical safety, to the children under its supervision.

Federal employees detailed to the Fort Bliss shelter, speaking on the condition of anonymity, told Reason they are working 12-hour shifts six days a week. Basic forms and equipment, including lice kits, are in short supply, and frustration is mounting.

In a recording of a recent training session for federal employees run by a staffer from Chenega, an Alaska Native–owned corporation that is providing workers for the shelter, the trainer acknowledges a variety of failures.

"I'm not going to lie, we've got people dropping like flies because it's just not something that they're used to," the trainer says in the recording, which Reason is not releasing to protect the source's identity. "This facility is growing so fast, and we are getting kids on a daily basis. We don't have enough staff to maintain."

The trainer also alludes to the poor conditions inside the tents, which house up to 1,000 people, each in stacked bunk-style cots.

"I've been into one dorm, one time, and I was like, yeah, I'm not going back there," the trainer says. "They're filthy. They're dirty. There's food on the floor. There's wet spots all over the place. The beds are dirty. I don't know what's going on or who's responsible for ensuring that the dorms need to be clean, but we all need to be responsible for telling the minors to clean up after themselves."

The trainer says there has also been inappropriate contact between staff and minors, as well as between minors.

"We have already caught staff with minors inappropriately," the trainer says. "Is that OK with you guys? I hope not. We have also caught minors with minors, which is, you know—we've got teenagers in this shelter. What's happening with teenagers? Hormones, raging out of control. It's important that we maintain safety and vigilance. Be vigilant. Stop what is happening. If you don't watch these kids, and you're not the one who is going to step in, who's going to? Be that person to stand up for the minors because that's what we're here for."

Children are also being ignored when they request medical care. "Some of the incidents and complaints we're getting also is that we've got minors who are requesting medical due to not feeling well, and staff members are telling them there's nothing wrong with you, go back to your bed," the trainer says. "These are legitimate complaints and it is my duty to let you know what is going on, because if you know who these people are, you need to report them."

Reason obtained another recording of a May 19 town hall–style meeting on health concerns at the shelter, led by Dr. Joseph Hutter, a commander in the U.S. Public Health Service.

"No one else says 'no,'" Hutter responds. "No one else says 'after lunch.' You let the tent nurse know. Nobody slows down or denies medical care, and if the medical tent is backed up, they can call on reserves. That shouldn't happen."

At the town hall, one person asks Hutter how many minors and staff have contracted COVID-19.

"This is a question, I'll tell you, that is hard to answer," Hutter says. "It has to do with data and transparency. Wouldn't it be nice if you had graphs and charts and hot maps, updated daily and everyone gets it every morning? If that graph is going to The Washington Post every day, it's the only thing we'll be dealing with and politics will take over, perception will take over, and we're about reality, not perception. The reality is the intervention to change the situation is to constantly improve our safety measures."

In the May 22 daily brief to staff, a shelter director notes that the area known as the "COVID Campus" is being renamed "Healing Hill."

Federal employees told Reason that several minors have attempted to escape by jumping the fence that surrounds the shelter. They do not get far, the federal employees noted, since they are still within a military base.

Youth advocates have also described unsanitary conditions at the Fort Bliss shelter. Leecia Welch, senior director of the legal advocacy and child welfare practice at the National Center for Youth Law, toured the tents recently and told The New York Times that they "smelled like a high school locker room" and confirmed that the children were not receiving clean clothes.

"Many of the boys and girls have not been given underwear, particularly ones who've been in COVID isolation," a federal employee says. "After they come out, they're issued new clothes, but no underwear. And very often it's only one set of clothes, so no clothes to change into, and no underwear. When we have asked about it—and I personally escorted some kids to tents to ask how come they can't get underwear—the answer is, well, the contractor is supposed to provide that."

For one federal employee, the excuses are ridiculous. "There is no underwear shortage here in El Paso," the employee says. "I've checked at Walmart and Target. Anybody with a credit card could go and get all of this. And the answer is, everything is being monitored because we don't want there to be waste. The irony is just so rich. With the salaries they're paying us, and rental cars, hotels, per diems, and 72 hours a week—it's just mind-boggling."

The New York Times reported last week that the Biden administration is planning to expand the shelter to hold up to 10,000 minors. Because the shelter is inside a military base, it is not open to the public or press. Neither are any of the other emergency intake shelters. The photos in this story were snapped by a federal employee and passed to Reason despite an absolute prohibition on taking or sharing images imposed by camp officials.

"Secrecy is demanded at a level that might be called for if we were designing the next generation of nuclear subs, and there is absolutely no reason for it," a federal employee says. "One can understand the need to protect the identities of individual children and not allow them to be photographed. But there is no excuse for any of the other secrecy surrounding the operation."

HHS and Chenega did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Look at all of those photos frum the dark times during the trump administration

"You will own nothing, and you will be happy." Based on that expert analysis, these kids should be overjoyed. I don't get it...

Was that Marine boot camp, communist indoctrination, or an elementary school run by leftists?

Start making cash online work easily from home.i have received a paycheck of $24K in this month by working online from home.i am a student and i just doing this job in my spare ?Visit Here

Yet not one of them would have trouble getting a mail in ballot.

Bingo.

Because most are several years older than they claim to be, they’ll also use up resources meant for actual children.

For many of these migrants pretending to be children, the first time they’re exposed as adult frauds is when they get arrested for impregnating American teenage girls.

Want irrefutable proof that Biden has reversed Orange Hitler's draconian anti-immigrant policies?

Let my favorite Congressperson AOC guide you. Her tremendous compassion for immigrant rights inspired her to literally break down and cry because she was so upset by Drumpf's concentration camps.

And have you seen her make any comparable protest during the Biden Administration? No! Because Biden fixed the problem.

#LibertariansForBiden

#OpenBorders

#(EspeciallyDuringAPandemic)

She called for reparations to be paid to migrants from Guatamala because of past US foreign policy and criticized the detention policies of the Biden administration as barbaric and inhuman. Just last week, GOP drone. Is your only purpose here to excuse past GOP policy failures?

That doesn't do anything for the kids living in these conditions. Keep swinging sooner or later you might get a hot Casey.

Funny thing is, it's conceivable that there are people still alive who helped the PHS/NIH inject Guatamalans (average age of 20 with 'subjects' as young as 10) with syphilis without consent. An actual case where demonstrable harm was done directly and survivors are still actually owed reparations.

Reparations paid? Sure. Obama apologized to Colom and promised never to do it again. District judge ruled that, despite there being no question of guilt of crimes against humanity among any of the parties, the US (Sebelius) has/had immunity.

A watermelon of a pitch right in the strike zone and the 'reparations' crowd says, "I'll swing at the next one."

"She called for reparations to be paid to migrants from Guatamala"

Lol, did she really? That's hilarious.

What an insane clownshow these people are.

It's funny he thinks that was a good point to make. It doesn't address the problem and it is laughablyplaying to the the caricature of Democrats as having only one answer to anything, throwing taxpayer money at it.

I’m not for throwing any tax money at ICE. You?

So there's *ONE* program you don't want to get funded, you pathetic lefty parasite?

This is a parody account, right?

No, he’s for real. Sadly.

You must have hated the Berlin Wall.

Probably too young to know what that is.

throwing any tax money at ICE

Federal funding for the federal agency, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement?

Are you retarded to think that is somehow extraordinary?

What the fuck did you think it was?

A militia?

A private security company?

Quite a lot of it is a private security company. Most of the work and services are provided by contractors.

Which is sort of beside the point, and I'm sure you knew that.

Ho. Hum. Nobody cares. Can't we move along and talk about something else? This shit is sooooo boring! Gol!

UFOs!!!

tool did the best song ever about a UFO encounter.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qnlhVVwBfew

Amazing song.

That report next month should be interesting.

Police brutally?

Lefty scumbags?

Cassandra Peterson turned 69.

Ft Bliss is a training site. Maybe Tradoc should be put in charge. A couple round browns will get those tents cleaned up in a hurry and establish order pretty quickly and more cheaply than bureaucrats and contractors.

I have found that, when planning to travel, it is wise to arrange accommodation ahead of the trip. Perhaps this vital step was overlooked.

I agree it is wise to arrange accomodations ahead of time. However, it isn't possible to plan for every possible contingency, such as missing a fight due to weather, or getting detained by INS.

Being detained by law enforcement is something to be considered before committing a crime.

Biden keeping hispanics in internment camps. That is what you need to say from now on.

Kids in shipping containers.

What is it about Democrats and internment camps with inhumane living conditions. At least Biden hasn't thrown American citizens in these camps unlike the Democrats hero FDR.

Yet.

True day!

So you guys are being nakedly hypocritical to care about kids in camps now that you think you can lay this at the feet of democrats?

Ok. As long as you do care. This is outrageous, and we should demand our government stop treating children inhumanely.

Now, if only you could go back in time and rescind Trump's DHS memo on creating the zero tolerance policy that led to this in the first place.

Where's your outrage at these kids parents? Or at the governments of their home countries? Here's some advice. Grow a pair.

He doesn't believe in personal responsibility when he can blame a conservative.

Here comes Jesse to put words in my mouth.

Don't you have anything better to do? Evidently not. Here, hold this till I come back and tell you to stop.

Jesse has like 3 tricks:

1. whataboutism

2. strawmen

3. insults

He's not worth the trouble.

What an asshole.

That's you're curriculum vitae, not Jesse's.

It's amazing how mad you paid shitposters get when guys like Jesse call you out on your bullshit.

What good would that do? I vote, I've been active in political campaigns. I can effect American policy minutely, but the attitudes of foreign parents not at all.

Yeah you voted, you voted for this and can't muster up the least complaint against their home country governments or the organizers of these marches or the families that send their kids here. You save all your opprobrium for the people here that object to it. Want someone to do something about this? Open your own home to a good dozen of these kids. Open your own wallet to feed and clothe them. Don't expect others to assuage your white guilt.

"" Open your own home to a good dozen of these kids. Open your own wallet to feed and clothe them.""

Yep, let's start a sponsorship program and watch how quickly people stop talking about it.

Outrage at the parents? I have a lot of sympathy for them. Things must be very bad for them if they would contemplate sending their kids on such a journey.

In your case when I said grow a pair I meant giant milk filled titties. You can head on down there and suckle them to your heart's content.

Agree!

complained when O did it too.

You really can't stop being a biden cultist. Lol.

Trumps border looked to reduce the number of camps needed for illegals crossing. Bidens policies actively encourage illegals to cross.

^^^THIS

True.

Yes. We have different types of facilities to house migrants, not all of them are equally as bad. The reason there are so many kids in these badly managed camps now is because the number of crossings are greater. Trump made an arrangement with the Mexican President for them to guard the border as the wall was finished and because of that the number of migrants dropped.

Being liberals don't seem to understand the scarcity of resources, I'm not surprised they don't understand the complications of handling a situation that becomes overwhelmed. They don't understand the work involved. They have an idea and they think it can magically happen without its own set of consequences.

I mean.... your too stupid to know these camps existed before trump under Obama. Just wow.

You are too dishonest to acknowledge the zero tolerance policy that precipitated all of this.

It didn’t. Biden telegraphing amnesty did. You’re either too stUpid or too dishonest to admit that. Or some combination of both.

DOL is extremely dishonest.

Stolen Valor has been a liar from the beginning.

"So you guys are being nakedly hypocritical to care about kids in camps now that you think you can lay this at the feet of democrats?"

Calling steaming piles of lefty shit like you on your hypocrisy is not being hypocritical; it's pointing it out.

Trump did his best to prevent foreigners who did not qualify for residence from crossing the border and getting into INS custody in the first place. Biden effectively invited masses of undocumented immigrants - without asking Congress to change the laws under which INS is supposed to cage them pending a final determination.

HaHaHa!

""So you guys are being nakedly hypocritical to care about kids in camps now that you think you can lay this at the feet of democrats?""

Well that's exactly what the democrats did when the photos from 2014 resurfaced. I don't hear democrats taking Biden to task and it's still going on.

Of COURSE they do... that's why it's a fucking crisis! That's why when a semi-retarded presidential candidate tells the world, "If I get elected, make a run for the border!!!" is not "wrong within normal parameters".

Incitement and then lockup.

But if we don't get runs on the border then how will the billionaires build their permanent wage slave underclass?

Why was an Alaskan Native Corporation given this contract? What was their expertise in dealing with these issues? I lived in Alaska and the Native Corporations don't have good reputations for efficiency or protecting youths (research the sexual abuse crisis in Alaska Native villages if you want a true horror story).

But like most reservation governments have a reputation (well earned) for corruption and nepotism.

Canada too.

A lot of these reserves are still run by hereditary chiefs and the elders are their brothers, uncles and cousins. A mafia family is a good equivalent for how these reservations and tribal corporations operate.

Yep.

A mafia family is a good equivalent for how these reservations and tribal corporations operate.

Slight disagreement:

Mafiosos frequently feel a sense of guilt or recognize a debt owed to the community. Nepotistic Reservation governments, OTOH, are owed these jobs and their supporters consider the times when people starved while hunting bison with sticks to be an ideal. I'd agree that a cartel would be a good analogy.

They've got lots of federal contracts. And they don't need expertise, they've got something even better: minority set asides

Bingo! The question was sort of rhetorical as I knew the answer. But look at any Alaska Native Village and try to act surprised by these conditions.

we said ICE, not ice ...

LOL

Because they know how to blubber.

Most likely explanation is that they already had a contract with the base for something else, and it's far, far easier to add more stuff to an existing contract than it is to go through the whole multi-year process of getting a new contract approved and signed.

DDG: Endeavors Pecos contract

500mil no-bid awarded to Dem donor

Don't worry, as soon as Kamala takes over, she and AOC are gonna take care of it.

I thought that Biden appointed Kamala to lead the White House effort to "tackle the migration challenge at the U.S. southern border" (as per the AP story I just checked). I guess that because these teenagers crossed the border, she's not paying much attention to them at this point.

theyll allhave diseases if she gets involved..

Why wasn't Reason whining a and crying when Obama did the same thing? They only complained because Trump was president, and now that he's not president anymore they're giving it a pass. Fucking Democrats running the magazine. I mean, this is just bitching about Trump and nothing more.

Hey Sarcasmic,

Up above your post about how Reason doesn’t publish criticism of immigration policy under Democrats there’s an article criticizing immigration policy under Democrats. You might want to read it, bud.

See you missed his sarcasm. That was his point idgit.

Got it.

Look at all these Trumpians fucking celebrating this brutality because it hasn’t ended under Biden. They’d have a point if they advocated closing these detention camps and integrating immigrants into the society as a whole. But they don’t. They’re just gaslighting and bullshitting— as usual.

It didn't end it got worse. Guck keep swinging.

And if this story is true, not only worse but a lot worse and a lot larger and more inhumane. Trump's gone time to move on and criticize a crisis that is worsening and leading to inhumane conditions that were never present to this degree under Trump. For all his faults Trump never did anything this bad. But you still want to blame him rather than address the current (worse) problem. Pure partisan bullshit.

I’m for getting rid of these detention camps and reuniting the kids with their parents. I’m also for letting their parents live and work where they would like. You?

No, I am for some minor form of border control to keep out criminals and terrorist not a free for all, like most libertarians I realize the need for some form of border control, even if it is a simple background check, but am not total open borders with no checks. The problem is that under the current system it takes to long to process these kids and releasing them isn't any better of an option. But that doesn't mean we can't insure basic hygeine, medical care and other humane treatment while we process them. I oppose total open borders while supporting a liberal, humane immigration system that protects citizens while treating immigrants humanely and expeditiously. Do you oppose any background check or any form of border enforcement? Because if you don't you still need to process people and unaccompanied minors from a third world country takes time to process. Period.

That is basically where I am at too.

"...I’m also for letting their parents live and work where they would like. You?"

I'll bet more than a couple would be more than happy to move in with some parasitic piece of lefty shit like you.

We can expect a report real soon, right?

And thats what sarcasmic can't do, blame the worsening situation under biden because then he'd have to admit he was a completely ignorant person the last 5 years.

Spot on!

El Paso has been dealing with illegal immigration for centuries and it's still one of the safest cities in the good old US of A. We don't need some rich trust fund so called politician from NY that's never lived a day in an El Pasoan's pantalones to tell them how to run their city!

Uhm Ft Bliss is outside city limits and it doesn't appear from this story anyone is handling it very well on Bliss. And this is a problem created by someone born in Pennsylvania and raised in Delaware not New York. Try to keep up.

Oh really! By the way, we ever going to have those beers we talked about a long time ago?

Since the story is about Ft Bliss... Yeah really.

Ft Bliss is also not ran by people of El Paso who have nothing to do with this story or the conditions. What an obvious head fake.

El paso has a large contingent of federal agents in the city...

So what? Why is El Paso the standard?

You understand the federal government is taking border crossers from El Paso, putting them in detention camps outside El Paso, then putting them on buses and planes to towns and cities all over America.

What percentage of El Paso residents work in law/border enforcement?

Fuck you. Who's "celebrating" this? No one. But people are rightfully pointing out that the scrutiny given (and the corresponding "outrage") under the previous administration seems to be quite different now. There is also honest discussion as to best solve this problem: should we just fling open the borders and let everyone in and sign them up for citizenship with all its benefits right away? should we finish the wall and patrol the border? should we detain people here or send them home? That's not "celebrating".

☝︎

"...Look at all these Trumpians fucking celebrating this brutality because it hasn’t ended under Biden..."

Look at all the TDS-addled assholes trying to ignore that Biden is making a worse mess than Trump managed.

You got that right!

Whatever!????

Got it.

No, you didn't. When someone tosses you a roll, you let it hit the floor, and cry until someone picks it up and stuffs it in your face, you didn't 'get' it.

Thats not sarcasm. It his usual hyperbolic strawman creation to try and attack the right.

His statement has no value against the use of camps or the negative parts of bidens policies.

He is trolling.

God damn youre broken.

Instead of calling out the policies you attack conservatives... yet you claim you aren't a lefty.

Here you are free to attack biden and you couldn't.

If you promise to always say how great he is, he’ll criticize a Democrat.

Maybe Tradoc should be put in charge. A couple round browns will get those tents cleaned up in a hurry and establish order

https://wapexclusive.com ,pretty quickly and more cheaply than bureaucrats and contractors.

So are you another handle for soldiermedic? You just posted virtually the same comment.

Poor Dee still doesn’t know how the bots work. Idiot.

"we all need to be responsible for telling the minors to clean up after themselves."

"Por favor, limpie después de ti mismo."

Your tax dollars at work. Maybe we should get rid of these camps and let people who want to come here do as they please.

Nope. Finish the wall, and line the marxists (like you) up and shoot them. Then we can save this country.

This is a libertarian?!? Jesus Christ! You’ve changed, baby.

Marxists are the natural enemy of libertarians.

They are? Most Marxists were libertarians before the philosophy got contaminated with Randian psychobabble and rape fantasies.

Bullshit. Libertarian ideals are the opposite of Marxist ideals in the real world not in some fantasy world that never can or will exist. Marxism always will require a strong man to make it even halfway work. Libertarians oppose the idea of a strong man and support private property (opposed by Marxism) capitalism (always has even before Rand) and individual liberty before collective good (again the opposite of Marxist ideology, I've read Marx and he believed in coll drive good before individual good and liberty). Marc and Engels believed in violence to establish their system, believed in destroying classes, believed in ending property and believed in collective good and the cost of individual liberty. Any Marxist who thought he was a libertarian was deluding himself. Then again Marxism has always been a delusion because it ignores human nature.

Marxism destroys the human spirit and individual autonomy; Libertarianism promotes both. That is the difference, in a nutshell.

More succinct than my explanation.

The European strain of libertarianism is much closer to pure communism than it is to anarcho-capitalism as it is in the US.

"The European strain of libertarianism is much closer to pure communism than it is to anarcho-capitalism as it is in the US."

Gonna bet that you have zero cites for that claim, and it's nothing more than an expression of your 'Euro-fantasies'.

Put up, or STFU, asshole

Bertrand Russell? George Orwell?

So, zero cites; not unexpected from a lefty ignoramus

Lefty puke thinks he’s George Orwell. Next, Shit For Brains will tell us that the border jumpers plight is the same as The Road to Wigan Pier. Admit that Biden made it worse bitch, admit it.

Pay your mortgage.

Most Marxists were libertarians before the philosophy got contaminated with Randian psychobabble and rape fantasies.

Cognitive dissidence.

"Most Marxists were libertarians before the philosophy got contaminated with Randian psychobabble and rape fantasies."

You are a lying piece of lefty shit who supports the most murderous regimes in the history of the world.

Nah... I never supported Nixon or LBJ.

Nixon and LBJ combined don't come close to Stalin or Mao.

"Nah… I never supported Nixon or LBJ."

"8. KIM IL SUNG (1.6 MILLION DEATHS)

[...]

7. POL POT (1.7 MILLION DEATHS)

[...]

3. ADOLF HITLER (17 MILLION DEATHS)

[...]

2. JOZEF STALIN (23 MILLION DEATHS)

[...]

1. MAO ZEDONG (49-78 MILLION DEATHS)"

https://sciencevibe.com/2019/11/13/which-evil-dictator-killed-the-most-people/

First, I know an uneducated piece of lefty shit like you is going to gripe that you didn't support the socialist Hitler. To which those who have read history would point point out, that in technical terms, you're full of shit; he was a socialist.

And then, those estimates are on the very low end of most.

Now, steaming pile of (uneducated) lefty shit, let's see the number of *innocents* Nixon or LBJ killed.

Or you could do the world a favor, make your family proud and give your dog a place to shit but fucking off and dying.

Just to make sure you are held in proper contempt as the lying pile of lefty shit you are, and knowing full well that a lying pile of lefty shit like you would avoid providing cites, I saved you the effort:

"Some 365,000 Vietnamese civilians are estimated by one source to have died as a result of the war during the period of American involvement.[1]"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vietnam_War_casualties

Yeah, it's Wiki, but the number shown is the estimate of deaths on *both* sides. By comparison the the ~100,000,000 million murders committed by your heroes, it amounts to a rounding error. Unlike the number murdered by your heroes, it's small enough that even lefty shits like you haven't bothered to make asses of themselves by inventing numbers.

There was no excuse for that war at the time and none now, and you have every opportunity to cite anything which would support your pathetic attempt at 'equivalence'.

But what ought to cause embarrassment to a decent human being is the attempt to trivialize the one hundred million murdered by your heroes by comparing that to the perhaps 1% who *might* have died by US involvement in that war.

Fuck off and die, for all the reasons stated above and the added one that the total intelligence of the world would measurably increase.

Check that: 1/10th of 1%

I’m responsible for Mao Zedong now?!? Jesus Christ, that’s bad!

I’m talking about things that I was actually alive for. For example: I was vociferously against both wars in the Persian Gulf. A position I am very proud of. What was your position on Iraq? I didn’t see libertarians or Ron Paul types at the antiwar rallies I was at. That wasn’t until 2007. Most of the people at those rallies in 2002 and 2003 were commies and other undesirables.

Like most libertarians you guys are all antiwar when there’s no war, but when the state makes up some excuse to bomb a third world peasant there’s usually some carve-out in libertarian philosophy that allows the bombs and the brutality to issue forth. That’s too bad. Opposition to the use of force by the government is a noble position with a proud history.

If only you guys followed it.

We're you alive for LBJ and Nixon, because Mao was. So the comparison is apt.

“Like most libertarians you guys are all antiwar when there’s no war, but when the state makes up some excuse to bomb a third world peasant there’s usually some carve-out in libertarian philosophy that allows the bombs and the brutality to issue forth.”

You like to make up bullshit troll.

And I am not anti war just anti unprovoked war. There is a difference. I supported attacking Al Qaeda, and supported Iraq initially (although they didn't have anything to do with 9/11) but I was younger and more easily swayed. I doubt I support Iraq today despite the fact they did break 19 of the 25 clauses of the 1991 cease fire and therefore technically had resumed hostilities. But I wouldn't oppose say WW2 after Pearl Harbor but would have opposed WW1 because Germany never attacked us or threatened us. I would have opposed the Mexican American war right up until Mexico invaded Texas and would have opposed the Spanish American War buy not the War of 1812 because Britain was ignoring our sovereignty and pressing American sailors which is an act of aggression. Not all wars can be avoided but when we can't avoid them we should do everything to win, use all our conventional resources, to win which we didn't do in Afghanistan. And then get the fuck out.

"I’m responsible for Mao Zedong now?!? Jesus Christ, that’s bad!"

I for one, want to thank you for making such a transparent attempt to crawl out of the septic tank you already dived into, hoping that there were sufficient idiots here to buy your pathetic attempt to scrape the shit off of you!

There aren't.

You have once again shown the limitless stupidity and dishonesty which are the hallmarks of steaming piles of lefty shits.

Pathetic try:

No, you're not 'responsible' for the hundred millions murdered; you're responsible for your *support* for those murderous regimes, you steaming pile of lefty shit.

Let us know how your kids respond when you explain that Lenin, Stalin, Hitler and Mao were "OK" in having millions of those of their age murdered, but Bush was something else.

Well read in the spy-craft of the cold war; this pile of shit would be claiming saint-hood, and believing it.

"...Like most libertarians you guys are all antiwar when there’s no war, but when the state makes up some excuse to bomb a third world peasant there’s usually some carve-out in libertarian philosophy that allows the bombs and the brutality to issue forth..."

Like most fucking pieces of lefty shit, we are offered a bullshit claim absent *any* evidence.

Put up or STFU, asshole.

What about the most current war, the active war on the United States by Donald Trumpistan? All the power the United States armed forces can muster?

"What about the most current war, the active war on the United States by Donald Trumpistan? All the power the United States armed forces can muster?"

Another steaming pile of lefty shit checks in with more lies.

""I’m talking about things that I was actually alive for. ""

Is that the standard? I have people trying to hold me accountable for things that happened before my great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather was born.

You were likely supporting the CPUSA candidates.

This has to be parody...

This scumbag shows up once every 6 months or so spouting that sort of bullshit.

You want to make us all state slaves. And there’s isn’t anything pacifist about libertarianism. Slavers get eliminated.

You are free to abandon your Marxism and live in peace with the rest of us.

If not, that’s your choice. Just be prepared to burn for it.

But "line them up on a wall" types aren't?

You guys are seriously blind to your biases. At least try to acknowledge them.

Considering that is how Marxists always deal with political opponents, self defense is allowed by libertarians. Unless you don't believe in the right to self defense. Speaking of bias, you bringing it up is totally pot calling kettle black.

When I call DOL a sociopath, I’m not being hyperbolic.

Marx made no attempt to hide the fact he supported violence to enact his "utopia". Anyone who read him is aware of this. Many so called Marxists I doubt have ever really read Marx. And anyone who doesn't realize Marx was violent and ergo violence is at the root of Marxism also hasn't read Marx.

My philosophy is very simple. Leave me alone, or else.

Unfortunately, Marxist don't by believe in leaving you alone and are willing to use violence to obtain their "utopia". Certainly, Marx believed in violence to overthrow the system and eliminate the bourgeois. And all self proclaimed Marxist countries have resorted to violence, as have a large percentage of Marxist groups throughout the world, even in western Democracies.

I agree. Let's bring back child labor and get these kids working. Sewing underwear would be a good start.

First, get rid of the taxpayer spending. End the welfare state, stop taking my money by force, and then we can talk about the rest of the world's "human right" to come to the USA.

"Here, first accomplish this impossible task before I will consider acknowledging the human rights of people who don't look like me."

It is not an either/or proposition. And this framing contemplates that there is some necessary connection between immigration and the welfare state. There isn't. It's citizens who vote for the welfare state, not immigrants. It's citizens who are the overwhelming beneficiaries of the welfare state, not immigrants. Illegal immigrants aren't even eligible for welfare, legal immigrants are only eligible for very limited forms of it. There is nothing wrong nor inconsistent with advocating for an increase in liberty *overall*, which means reforming the welfare state, but also means liberalizing immigration restrictions.

It is a requirement for immigration reform to work that first you have meaningful welfare reform. And yes some immigrants do come here for the welfare well others end up on it rather they came here for it or not. I support immigration reform and liberalizing the system, but mpercy is right that short of welfare reform/elimination liberalized immigration would likely be a disaster.

It is a requirement for immigration reform to work that first you have meaningful welfare reform.

Why? Why does one depend on the other?

ALREADY, most immigrants are barred from most welfare. What more do you want?

The welfare that is often attributed to immigrants, more often than not, relates to native-born children of those immigrants, who ARE entitled to benefits because they are citizens.

If we liberalized the system it follows we would eliminate the work requirement. I mean it would be a simple background check to eliminate criminals and terrorist ergo you couldn't ask about self sufficiency could you?

If the government liberalized which system? The immigration system or the welfare system?

If the immigration system were liberalized, then in my view anyway, those wanting to come here could pass a simple background check and a simple health screening and that would be that. They would have a work permit to live here. NOT to be a citizen, just to work here. AS IT STANDS RIGHT NOW, immigrants aren't entitled to most welfare. They get emergency room health care, their kids get public school, and some states do offer benefits to everyone, and that's about it. They aren't eligible for SNAP. Some permanent noncitizens are eligible for Section 8 housing vouchers, so if you want to say none are eligible, then fine. But that is it. Where is this treasure trove of welfare benefits that are available to anyone who crosses the border? Where is it? It is largely a myth fueled by right-wing demagogues. YES there are some states that are more generous than others (e.g. California) but that is their decision, that is not a federal welfare benefit.

I am not arguing they receive copious amounts of welfare but liberalizing immigration would require welfare reform. Now your work permit idea is decent and may not but that isn't what most people propose when they propose liberalizing immigration. They propose full on immigration without a work requirement. Does California use federal dollars to support their welfare, if they do (which I know they do) then their decision isn't just their own but impacts everyone.

Well then if you agree that immigrants aren't sucking giant amounts of welfare off of taxpayers, then why do you make immigration reform dependent on welfare reform? Why do you insist that a relatively small injustice must be corrected before a VASTLY larger injustice gets rectified?

YES, absolutely, if immigration were more liberalized, there would be more immigrants consuming more public resources. But doesn't that pale in comparison to permitting more people to escape oppression and genuine poverty (not "American poverty", but actual soul-crushing human misery) in their home countries?

Not if it requires us to support them, thus requiring more taxes and therefore more oppression ourselves as taxes are enforced by people with guns. I am all for work permits and liberalized card check border crossings, if and only if, they are paying more into the system (like most Americans supposedly are but functionally don't anymore, which is another discussion all together) than they get from it. Immigration is a good thing, welfare isn't. And putting immigrants on welfare just leads to resentment and nativism.

"Well then if you agree that immigrants aren’t sucking giant amounts of welfare off of taxpayers, then why do you make immigration reform dependent on welfare reform?"

So something less than "giant amounts" is just fine.

There are many reasons you are seen as a steaming pile of lefty shit.

Or would we leave that, the work requirement in place? In which case you are being more restrictive than a simple card check system. would you also deport any immigrant who goes on welfare under your system. If you aren't willing to leave the work requirement and be willing to deport immigrants who go on welfare you first need to reform welfare or the whole experiment will fail.

I mostly don't care why people want to come here. I am not interested in interrogating everyone who wants to come here for their detailed rationales and motivations. Only if they are a wanted criminal or very sick would I say to keep them out. Otherwise, come on in. I would leave welfare decisions up to individual states, with perhaps some minimum standards set by the federal government (and if I were in charge, they would be very very minimal). If California wants to be generous while Arizona wants to be stingy, then that's their choices to make.

But honestly focusing on welfare in the context of immigration is a red herring. Immigrants represent a very small percentage of the welfare costs. It's citizens who vote for welfare, not immigrants.

At this time because of our current immigration system. That is the point. If you don't have some sort of rules and as long as states receive federal tax payer dollars it isn't just their decision it impacts everyone, you will have a possible quite possibly a probable, disaster. We just bailed out California didn't we by adding to the debt? As long as they receive federal money to support their generous welfare systems and can rely on federal bailouts (Reason has done lots of reporting on how blaming COVID was a red herring and the debt we bailed out existed before COVID in part because of their generous welfare systems) it isn't their decision alone. It impacts everyone.

That is a different discussion though. I agree that the relationship between the states and the federal government is messed up in terms of finances, and not just with welfare. But this is starting to sound like you want all of America's problems solved before permitting liberalized immigration reform.

No just see the need for welfare reform to make it work. If nothing else but to eliminate any misconceptions and to insure those who come here do so to help the country not only to benefit from it. I support your work permit idea. Just as long as it is better then the current H1 visas system.

and to insure those who come here do so to help the country

Who cares? Suppose someone wants to come here so they can live at their uncle's house and mooch off of their family and watch TV all day. WHO CARES? They're not harming anyone. It is a waste but that is their choice. Again I mostly don't care why they want to come here, as long as they are not wanted criminals or very ill. That's it.

And just to be clear, I favor work permits, not work requirements. I don't care if they come here to work or not. But they should have the legal ability to work if they so choose. Again the status quo rules ensure that they aren't eligible for most welfare. They get emergency room health care and their kids get public school and that is mostly it. So if they come here, they are going to have to work to support themselves, or be supported by some relatives. Again, so what?

As long as that remains the system and we don't end up with more Californias I will agree with you.

If wend up with more Californias (and leave the ones we already have) immigration reform will become unpopular and lead to even more and harsher nativism and likely lead back to zero tolerance and draconian rules. That is part of how we got to this place to begin with. If we want it to work we can't ignore what the populous perceives.

"Who cares? Suppose someone wants to come here so they can live at their uncle’s house and mooch off of their family and watch TV all day. WHO CARES? They’re not harming anyone. It is a waste but that is their choice. Again I mostly don’t care why they want to come here, as long as they are not wanted criminals or very ill. That’s it.

And just to be clear, I favor work permits, not work requirements. I don’t care if they come here to work or not. But they should have the legal ability to work if they so choose. Again the status quo rules ensure that they aren’t eligible for most welfare. They get emergency room health care and their kids get public school and that is mostly it. So if they come here, they are going to have to work to support themselves, or be supported by some relatives. Again, so what?"

You, as a lefty pile of shit, assume that someone showing up, avoiding productive effort, is not a drain on the economy.

I'm not going to waste time trying to educate you; you have proven to be stupid enough to lack the ability to recognize when you are lying, let alone learning anything.

Suffice to say, you are full of shit.

Okay. So suppose there was a new rule that said that only citizens were eligible for Section 8 housing. (Immigrants are already not eligible for SNAP.) Would that be enough? I suspect it would not be. I'm willing to bet that "welfare reform" would also insist that immigrant kids couldn't go to public school. I mean, I support privatizing all schools, but as long as we have public schools, I don't support having some kids uneducated. Do you think that should be the case?

No, that is a facetious argument not at all supported by anything I stated it implied.

What do you mean by more Californias? More of the fifth wealthiest state in the union? I mean, we can try to make Alabama into a Connecticut, but a California would be a huge improvement in and of itself, don't you think?

If CA is so wealthy they can afford to build their own train and leave the feds out of it.

And as for the children of immigrants it generally benefits the parents as well as the children receiving the benefits. So no matter what hairs you split it's still benefits immigrants having their children on welfare. And the bigger question is why anyone is due welfare at all. Especially if they pay little to nothing into the system. Yes, I know that is debatable, how much immigrants pay into the system vs how much they get from the system via their children and not all take welfare.

And if we liberalized immigration without welfare reform (currently immigrants are supposed to be self sufficient as a requirement for immigration) you will have even more coming here for the welfare. The US poor have a better standard of living than many of the third world inhabitants except the wealthy.

If I were to explain to you that immigrants, illegal or otherwise, actually provide extra support for the welfare state rather than drain it, would you all of a sudden be in favor of free immigration? I somehow don't think so.

The fact is your excuse for using taxpayer dollars to brutalize humans is a lie. Immigrants skew younger relative to the US population. That means, even if they participate in the system, they are paying into the welfare state, not drawing from it. The people drawing from it are elderly white people.

If you care about the health of the welfare state, you would put out signs advertising good work for all the immigrants who want to come, since, again, working age immigrants tend to be young and thus net payers-in to any social system.

The real problem for the welfare state is the aging population, not immigrants, many of whom, as chemjeff already explained, don't even participate anyway.

Since all of this provides you with just the rationale you need to stop favoring a brutal expulsion regime, the question is why you don't simply adopt it and solve all of your problems at once.

Did you read what I wrote above about supporting liberalizing welfare reform? Because you just made a fool of yourself with your asinine assumptions.

Here is what I wrote: No, I am for some minor form of border control to keep out criminals and terrorist not a free for all, like most libertarians I realize the need for some form of border control, even if it is a simple background check, but am not total open borders with no checks. The problem is that under the current system it takes to long to process these kids and releasing them isn’t any better of an option. But that doesn’t mean we can’t insure basic hygeine, medical care and other humane treatment while we process them. I oppose total open borders while supporting a liberal, humane immigration system that protects citizens while treating immigrants humanely and expeditiousl

I don't support the current system but see the need for welfare reform as part of a liberal, minor control system. I know it is easier for you Tony to argue against caricatures then actual human beings who are complex and often don't fit into your biased narratives.

Your deal was liberalized immigration policy in exchange for welfare reform. Since that is a false choice, not to mention nonsensical*, we are now at a place of agreement. Let them in, get more productive humans paying part of their salary into the welfare state, and it's a win-win all around, n'est-ce pas?

*Nonsensical because if you're concerned about the financial health of the welfare state, your solution wants further explanation. You don't cure a sick person by murdering them.

Bad analogy. So you admit I don't support brutalizing them now. So your backtracking. Careful you might fall running backwards like that.

And if you want to apologize for mischaracterizing my stance on immigration this is where you would do it. But I doubt you have the intellectual honesty to do that

Have you bothered to read any of my replies, because I stated my actual positions which once again you misread and mischaracterized.

People are being brutalized by the current system. You favor keeping the current system until some other unrelated policy choice is made.

From a purely humanist perspective, this looks like brutalizing a group of poor people (A) while you bide your time waiting for another group of poor people (B) to have their food and housing taken away from them.

It's all very compassionate in theory, I'm sure.

Wrong once again Tony. Keep digging and mischaracterizing what I stated multiple times. Just keep it up. I stated for it to work both systems need reform not that we can't reform one without the other, just that it won't work. And I never argued for continuing brutalizing people in fact I argued against doing it and treating them humanely until we get a new system. Guck can you make an intellectually honest argument?

Brutalizing is my word, and I'm using it to describe the putting of children into any kind of cage.

Immigration restrictions may or may not be a necessary evil in a world with nation-states, but they come at such an enormous cost to our moral stature as humans that one wonders why we don't try harder to fix the problem, especially since it's completely a matter of putting a signature on a piece of paper.

I do, however, believe you are offering the most compassionate policy approach that is reasonably to be expected of you.

The fact is your excuse for using taxpayer dollars to brutalize humans is a lie.

That isn't fair. I appreciate that soldiermedic wants his tax dollars spent wisely. I don't think he wants to brutalize anyone. I just think his cost/benefit ratio calculator needs to be rebalanced, that's all.

Tony argues caricatures not actually what people believe. He truly believes that the world is good and evil and anyone who disagreed slightly with him is evil. And no based upon my many years experience with him I don't think I am being harsh. As for my analysis of th cost benefits, I laid out my analysis which some of it you agreed with. Unfortunately, the system is so complex anymore that I can't ignore one thing without worrying about it's impact on other things. In this case welfare and immigration. If we end up with, which I believe is possible, a bunch of immigrants allowed onto welfare under the liberalized immigration system I support, then it will fail and leaf to even harsher nativism.

The root cause of nativism is not welfare, but prejudice.

To the nativists, it literally does not matter how much welfare that immigrants consume. If it was only $1, there are willing demagogues who will create entire news stories about OMG DID YOU SEE THAT THOSE IMMIGRANTS ARE STEALING YOUR HARD EARNED TAX MONEY? THOSE MOOCHERS!!!! The amount does not matter. It is that they are here at all, and doing anything at all, that upsets them.

"The root cause of nativism is not welfare, but prejudice."

Lefty assertions =/= evidence or argument.

Fuck off.

But the recruit using systems like welfare as their Boogeyman. I am being pragmatic because I would like it to work not fail and lead back to what we have now. I support work permits but think a requirement would be good also,as long as we make the permits transferable. E.g. if they work for rancher A and Rancher b wants to pay them more they should be able to quit and go work for rancher B without threat of deportation (unfortunately HIs don't allow this currently).

Don't let the nativist bigots define what is right or wrong. If they falsely believe that immigrants are just swimming in a pile of welfare money then that is their problem and maybe they shouldn't listen to Fox News.

Let me put it this way. Suppose you had two children, Alice and Bob. Alice said "I made a mistake, I spent $10 at Burger King that I know I wasn't supposed to, and I'm sorry." But Bob said "I made a mistake, I spent $100,000 buying a Lamborghini that I wasn't supposed to, and I'm sorry." Now if you got more upset at Alice for her much smaller purchase, as compared to Bob for his much more outrageous purpose, you might think that the real source of the outrage wasn't actually related to the dollar amount of the expense, but was related to other factors.

That is exactly the case when it comes to welfare and immigrants. Even by the right-wing's own standards, immigrants consume something like $200 billion in welfare benefits annually, and that is a grossly inflated figure. Well, the total cost of the welfare state is around $1 trillion annually. If your friends tell me that they are more upset by the $200 billion than the $800 billion that everyone else consumes, then I"m going to say that the real reason for the concern isn't related to the dollar figure. It's related to WHO is receiving the money.

My point is that not all nativism starts out as prejudice, and the actual number of true nativist who hate all immigrants is small. But they use welfare and other systems to sway the public to their side. And as long as they receive even as little as $1 it will make their argument easier. We live in a republic not libertopia. We have to persuade the public and without welfare reform that is a nearly impossible task. People don't like welfare but see it as a necessary evil (with exceptions) people generally support immigration if they are seen as contributing more than they consume. Those are the realties. To be pragmatic and make it work we have to appeal to both emotions and logic, which is difficult. It is even more difficult if we give up an emotional argument to the other side (e.g. immigrants receiving any form of welfare).

And my argument is is why are they consuming even one fifth. And yes the whole system sucks. But you can't ignore the argument just because you dislike it. You can't persuade people that way.

Why don't you tell me, why does 20% of the problem (at most) receive 95+% of the outrage?

In a perfect world I would eliminate all welfare. But as we don't live in a perfect world leave in place rules that only allow citizens to get welfare and make welfare harder to get. Maybe privatize welfare. Give the money to charities who then distribute it rather than it being a government system.

20% of the problem doesn't receive 95% of the outrage. But even if it did it is because they came here and are now benefitting from something people perceive them not paying enough into.

20% of the problem doesn’t receive 95% of the outrage.

Among Team Red, oh yes it does.

But even if it did it is because they came here and are now benefitting from something people perceive them not paying enough into.

Okay, so they represent 20% of the welfare problem (at most). However, they are 95+% unlikely to be murdered by Central American gangs or to be murdered by Central American death squads.

At some point, we have to say "this cost is worth the benefit that these individuals receive".

We are never, in our lifetimes, ever going to see a system in which immigrants never consume any public resources. So then it becomes a question of whether the public costs that they incur are worth the benefits in terms of liberty. I think the answer is obvious: I'm willing to pay for public school for an immigrant kid if it means the family isn't murdered by Guatemalan death squads in their home country.

No it doesn't from team red. Now you are devolving into partisan bullshit. We were having a good discussion until you decided to demonize and mischaracterized the arguments and beliefs of about half the country that disagrees with you.

"...Okay, so they represent 20% of the welfare problem (at most). However, they are 95+% unlikely to be murdered by Central American gangs or to be murdered by Central American death squads.

At some point, we have to say “this cost is worth the benefit that these individuals receive”..."

Assertions from lying piles of lefty shit =/= arguments or evidence.

"Tony argues caricatures not actually what people believe. He truly believes that the world is good and evil and anyone who disagreed slightly with him is evil...."

Absolutely correct, and further, shitstain is not capable of honest engagement. His initial post is likely full of lies or misdirection, and if you bother to engage shitstain, his response is yet more of the same.

There is no reason to engage that asshole at all; refute his supposed 'arguments' in the third person.

Simply point out his idiocy and move on,

I do have a political bias, insurmountable to this day. I think we should focus on not endangering the physical well-being of human beings before we worry about the bill. Providing for the basic dignity of human beings is the whole reason we get up in the morning. The details are a matter of applied economics. Don't give me an excuse for why we can't ensure that a child has a roof over her head, if that excuse is anything other than "we tried our best and failed."

If you keep repeating the inflammatory lie that immigrants strain the welfare state, I'm going to keep pointing out that it's an inflammatory lie. You can't hang your policy choices (choices apparently have no choice in) on a lie. We both know the motivation here is largely ugly and racist. You would need to separate that chaff from your wheat carefully, I presume.

"Providing for the basic dignity of human beings is the whole reason we get up in the morning.''

It needs nothing more than to point out that shitstain claims this to be true but provides no evidence that s/he does so.

This is bullshit 'signalling' that (by shitstain's emotions) we *should* do something or other, while allowing shitstain to do nothing of the sort, since shitstain requires others to do so.

As mentioned elsewhere, this is just one more example why it is not worth engaging a lying pile of lefty shit like this.

I never stated they did. Quote me saying they did.

In fact I stated the opposite yo chemjeff above. Guck you are bad at this. Reading to hard for you?

Sorry, I'm really just using you to bounce my self-righteous lectures off of.

If we can move past your indignation, could we talk about why my points are wrong? Failing that, why I'm a handsome and interesting person? Any juice for the dopamine smoothie will do.

Moron spouting cries of racist. Tony, YOU RE the racist. You need to stop with your Marxism before Americans are forced to execute you in self defense.

Abandon your bullshit beliefs if you want to live.

Why don't you say my ideas back to me and we can discuss any flimsy bits.

“Here, first accomplish this impossible task before

I will consider acknowledging the human rights of people who don’t look like me.making it more impossible to accomplish and more likely to hurt more people/consume us all.”FIFY.

""Maybe we should get rid of these camps and let people who want to come here do as they please.""

Do as they please? I can't even do that. Why should they be awarded greater freedoms than citizens?

Libertarians are small government, not free for all. Like every other country in the world, if they come here they must follow the laws of the land everyone else in that country must follow.

I consider myself a fairly open borders person, but it must include reciprocity. I never hear about how other countries must open their border, just us.

How do these conditions compare to the conditions on the trip north?

Inquiring minds want to know.

Reason:

(1) Open the borders! America needs young, cheap workers!

(2) Provide free housing, healthcare, services at taxpayer expense!

(3) Libertarian moment! Enjoy!

Collect tax dollars from #1. Stop paying the big salaries they get in ICE. Libertarian moment.

Yeah, they’ll pay big taxes and won’t use any services.

"Collect tax dollars from #1"

Already do, asshole.

You know who else lacks underwear and access to mental medical care for TDS?

Good 'ol Sevo!

Projection from a TDSS-addled asshole; cute. Stupid, but cute.

In this article, I learned that the difference between "keeping kids in facilities" and "keeping kids in cages" is whether the chain link is inside or outside the tent.

Frankly, it sounds like the kids were better taken care of under the prior administration, but it is hard to tell, as with all the histeria about chain link being a crime against humanity, we never really heard how well the kids' basic needs were being met. The fact that media has largely been banned from "facilities" while they had some access to take pictures of "cages" isn't exactly a good sign.

Good point.

More than 4,500 immigrant children and teens are being held in enormous, filthy tents on a military base in Texas without access to basic necessities, including underwear.

So they're being made to feel at home?

All this for a "not Trump" immigration policy.

The 'volunteers' are getting paid, overtime in some cases, and per diem, which in federal speak means they can stay in very nice hotels, or in hovels, and keep the difference. Dine at pretty nice restaurants, or McDonalds...

And who is responsible? The Joetato Head, of the State, and the horizontal hobama...

https://twitter.com/JackPosobiec/status/1396887967285882887?s=19

SCOOP: Leaked State Dept Cable Outlines Plans for Embassies to Fly BLM Banners Ahead of George Floyd Anniversary

[Link]

Here is Blinken’s action request cable to ALL DIPLOMATIC AND CONSULAR POSTS of the United States on BLM language, banners, and flags [link]

Blinken’s action request states the policy objective of the US govt is to promote ‘racial equity’ and ‘global racial justice’

In his honor all stations should broadcast the “Big Floyd” videos.

It’s not like anything else is going on the world

“Global Racial Justice”. Indeed, the US taxpayer, infrastructure and assets can right every wrong since the beginning of time.

Hamas will have a celebration over Isreal skies in honor of blm.

This is was enabling looks like.

*what

...and this is what enabling typos looks like.

No edit button but we do have a mute button.

So no link to the supposed recording, and all the pictures you could produce look like the facilities are pretty clean. More hack reporting from the ironically-titled "Reason" magazine.

They did not release the recording to protect the identity of the person that recorded it.

In ancient times, before January 2021 (circa 2016-20), the MSM would have screamed a story like this like an unending banshee.

But a small, insignificant internet publication Emote (formerly Reason) has the scoop.

Interesting times.

Most popular president ever!

Some O/T news, here goes:

China moving on Taiwan. Taiwan contains the world’s most important corporation for free world economies,( semiconductors)full stop…Jim Cramer. The EU sells 25 percent of their products to China. Will the EU stand with China or Taiwan?

More Chinese Communist Party news as the Maoist (drug cartel) group Shining Path kills 14 people in Peru and burns children’s bodies beyond recognition ahead of the election which is supposed to go to a CCP Maoist plant.

Chuck Fina. The cheap goods come from there. We need to protect TW.

"We know they are lying. They know they are lying, They know that we know they are lying. We know that they know that we know they are lying. And still they continue to lie."

—Alexander Solschenizyn

But hey! No more mean tweets!

Priorities!

The phony "libertarians" on this site spent four years ferociously attacking Trump and carrying water for people who can only be described as fascist totalitarians.

You don't get to pretend to care about human rights now.

I know, right? The people who were consistently against "kids in cages", whether under Obama, Trump or Biden, have no moral standing to complain about kids in cages!

"I know, right? The people who were consistently against “kids in cages”, whether under Obama, Trump or Biden, have no moral standing to complain about kids in cages!"

You're considered a lying piece of lefty shit for a reason; let's see some cites regarding opposition when Obo was presiding over the same practices.

Further, let's see some current (post Trump) cites from those 'consistently against' such practices.

I'm guessing, like Tony claiming the taxpayers were paying Trump's daughters for their assistance, you'll have the same number of cites: Zero.

Stupid, stupid Jeffy. The border crisis is your fault. You filthy progs told those people to come here and then you out the kids in storage containers.

That’s on you, not us.

Why are you Russians still around, the election is over comrade.

As opposed to “real” libertarians who are much more like, yourself.

“You don’t get to pretend to care about human rights now.”

I don’t “get to” do what...wait.

Donald Trump presided over the largest mass-death event in American history.

How much does he have to fuck raw on live TV before you wonder whether he might not have been a natural born leader and scholar?

"Donald Trump presided over the largest mass-death event in American history..."

Lies like this from shitstain suggest the reason there is nothing good from engaging a steaming pile of lefty shit like this.

It might be worth asking for (ha, ha) a cite to support that idiotic claim, but you're not going to get one and you will be accused of some sort of, uh, something.

Shitstain, several years ago, defended morning drunkenness, and it seems that support has now extended to 24 hours.

Isn't it time for you leave mommy's basement and head off to your job at Starbucks? Dont be late.

Not by percentage of the population. That would be Wilson who did that.

Actually as much as 850,000 died from Spanish flu in the US COVID has killed 590,000 so both by percentages and raw numbers Wilson takes the cake and Tony is wrong again.

#Winning!

Just admit you are wrong. People will pay more attention to you when you admit your mistakes. Otherwise they dismiss you ad a partisan hack incapable of intellectually honest discourse. And a partisan bigot who is ruled not be logic and intellect but by hatred of the "other side".

Covid deaths are undercounted, but fine, second-worst.

Mostly I just like to get you to admit how dismally horrible Trump was in the midst of your nitpicking.

Nope. It’s all your fault. As usual. Trump did pretty well, I’m spite of you. It’s only through our infinite mercy that we have allowed you to live.

I presume you speak for all libertarians.

There's only one reason to kill anyone over political differences, and that's, specifically, no reason at all.

""I presume you speak for all libertarians.""

Something an intellectual would not do.

Covid deaths are

underovercounted.FTFY

It must be liberating giving yourself permission to believe whatever you want to believe. Like a buffet for every thought.

Anyone with a credit card could go to a Target or a WalMart and buy a bunch of clothes, socs and underwear for the kids, but if someone from a federal contractor did that without taking formal bids and verifying that the suppliers have been certified to meet all of the Federal compliance requirements (drug free workplace, ADA, Davis-Bacon, etc) as well as making sure that a certain percentage of purchases are made from properly registered woman/minority owned (aka "disadvantaged") businesses, they'd be subject to prosecution and their company could be debarred from doing any future business with the government. There may even be a "made in the USA" requirement for their purchases, which would eliminate almost every mass produced textile item on a retail shelf in the U.S.

If only someone with some influence among those who make the laws that have established all of these restrictions considered the situation to be a problem worth addressing via the one process by which legislated laws can be changed...

So the Useless Nations go ' round the globe using the US mil to invade all sorts of nations embroiled in crime and humanitarian disaster EXCEPT MEXI- HELL.

WHYS THAT?

We could take Mexi- hole over, and do a lot of good at a currency rate of 14:1.

Why doesnt who want to?

"Where's my cable TV, Steak Dinners, Stripper show and back massage!!!"...

Reminds me of the prison population outrage 30-years ago.

So; They broke into their neighbors house ILLEGALLY and are now crying because they couldn't find the right size underwear???

Hint, hint --- GO BACK TO YOUR OWN HOUSE CRIMINALS!!!!!

You all keep proving my hypothesis correct every day - that for the modern Right, one's rights depend on one's moral worth.

"Good people" have the full panoply of rights that they may exercise.

"Bad people", on the other hand, don't deserve rights, they don't even deserve to be treated humanely.

When the recently evolved analytical part of the human brain, the part that makes us human, is turned off, the more ancient emotive and reactive part of the brain stays on. It's a wonderful trick our brains do when a wild animal or invading tribe pops into view: don't think; run, fight, or die.

Black/white thinking, translated into tribalism at the people scale, is what protected our ancestors from venomous snakes and what has caused every war in history. Any human being on earth really can love their neighbor one day and willingly see them marched into mass death camps the next, depending on what stimulus is provided for their brains.

Right-wing autocrats know this and know how to shut off the thinking brain and amp up the fight-or-flight response. Hence the evergreen politics of dehumanization.

Though I wonder whether, for some people, that advanced analytical brain that deals in gray areas and nuance was ever turned on in the first place.

Do you actually believe any of that garbage you are spewing?

I believe in the utility of science, because what else are you gonna do?

Do you think a better explanation is that the brown people really are genetically inferior? That the content-free disgust you feel in your upper spine is the true nature of reality, not what Harvard-educated geniuses discover in their carefully controlled labs?

See?

Who are you even talking to?

"Do you actually believe any of that garbage you are spewing?"

Unfortunately, that's not the relevant question here. Shitstain has not the mental ability to separate reality from his fantasy life.

The question that matters is:

"Do you think anyone other than steaming piles of shit like you are going to buy that?"

Don't expect a coherent answer.

"You all keep proving my hypothesis correct every day – that for the modern Right, one’s rights depend on one’s moral worth."

Given that the "all" represent various opinions, we can correctly assume that you are a lying pile of lefty shit.

And by the way.

These kids are not "illegal immigrants". They are claiming asylum. They are actually obeying the law. That is why they are in camps at Ft. Bliss instead of on the run from Border Patrol agents.

"And by the way.

These kids are not “illegal immigrants”. They are claiming asylum. They are actually obeying the law...'

Lefty assertions =/= evidence or arument.

You really are a pathetic piece of shit.

"We could take Mexi- hole over, and do a lot of good at a currency rate of 14:1.

Why doesnt who want to?"

Anyone with the sense to think about what we would do with Mexico if we owned it. WE DON'T WANT MEXICO. We did conquer it once, in the 1840's, and we took the land north of an arbitrary line on the map - with only a few thousand Mexicans living there - and withdrew from the rest. And this was when Mexico was not nearly as big a mess as it is now.

long to process these kids and releasing them isn’t any better of an option. But that doesn’t mean we can’t insure basic hygeine, medical care and other humane treatment while we process them. I oppose total open borders while supporting a liberal, humane immigration system that protects citizens while treating immigrants humanely and expeditiously. Do you oppose any background check or any form of border enforcement? Because if you don’t you still need to process

https://wapexclusive.com , people and unaccompanied minors from a third world country takes time to process. Period.

So most of you

a) support the caging of children because they were born on the wrong side of an imaginary line and

b) only really care that Biden gets some criticism for it to make Trump somehow look better.

Despite Trump's entire political career being centered around exterminating the browns, but whatever.

Someone explain to me, using libertarian principles, what possible argument there is is to use taxpayer-supplied firepower to force people to live where their parents shit until they die.

People go where the work is. You can't possibly have a true free market with borders. Borders are government-imposed market distortions of enormous scope.

Just a rational argument in defense of guarded borders from a libertarian, please.

That’s totally ridiculous. We need controlled borders to help keep out terrorists, illegal drugs, convicted criminals and sex slaves getting into the country.

What do you have against sex slaves?

They'd probably be grateful to us what with the not being forced into sex slavery anymore. I mean fuck.

"Terrorist" is not a species of human. Terrorism is something people do. If you want to keep would-be mass murderers on the other side of a border, then you better hop to rounding up all your short-tempered white neighbors with arsenals.

"Illegal drugs" are what I spent my teens and twenties experimenting with casually, with virtually no barrier to acquisition other than a little expense and annoyance, no matter how militarized the Rio Grande was at the time.

Yes we are doing a great job keeping out all of those.