The Republican Attack on Voting Rights

GOP state legislators have introduced a raft of new bills aimed at restricting the fundamental right to vote.

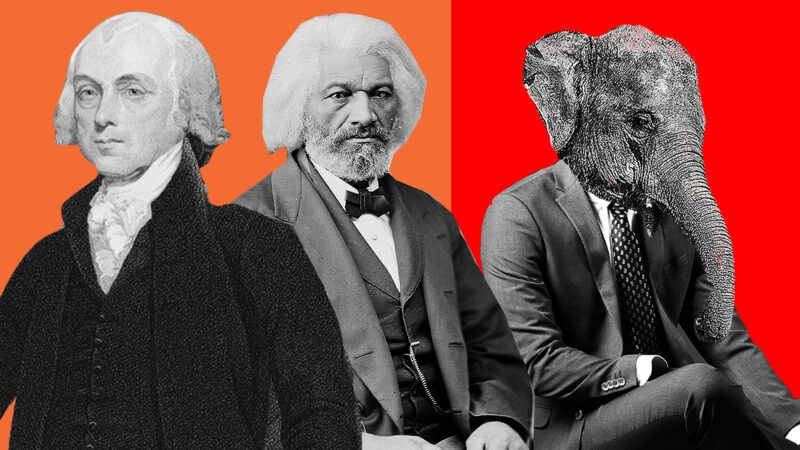

The father of the Constitution wasn't having it.

On August 7, 1787, toward the end of what would become known as the Constitutional Convention, the delegates debated what powers state legislatures and the Congress would have when it came to federal election administration. Some delegates in Philadelphia wanted state legislatures to have complete control over the time, places, and manner of federal elections. They worried about centralized power, an overzealous and suffocating federal government.

But James Madison disagreed. He worried about state and local machinations. The diminutive Virginia slave master worried aloud that it was "impossible to foresee all the abuses that might be made of the discretionary power" to control election rules. He worried about corruption. "Whenever the State Legislatures had a favorite measure to carry," he said, "they would take care so to mould their regulations as to favor the candidates they wished to succeed."

Madison eventually would win the argument, and Congress would get its veto power. Under the Constitution's Elections Clause, state legislatures would be responsible for running federal elections, but "the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations."

Madison has proven prescient. Throughout American history, state legislatures have wielded their powers to determine which Americans were deemed worthy enough to cast a ballot and give their consent to be governed. Nowhere was this clearer than in the Jim Crow South, where legislatures, with malice and artifice, took away the voting rights that millions of black men gained after the Civil War.

But this history has not ended. In the aftermath of a divisive election marked by allegations of widespread voter fraud, which led to the storming of the Capitol to overturn a free and fair election, Republican state legislators across the country continue to prove Madison's distrust correct.

A National Trend

As of February 19, 2021, Republican legislators in at least 43 states had introduced more than 250 bills to suppress or constrain voting, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law School, where I work. That's a sevenfold increase over the same time last year. The proposed changes include crippling limits on mail-in voting, restrictions on early voting, and reduced voter registration opportunities. These efforts, led almost entirely by Republicans, are a direct reaction to then-President Donald Trump's claim that the 2020 election was "stolen from the voters in a massive fraud."

But there was no epidemic of fraud. State and local Republican election officials confirmed the integrity of the vote. Trump's legal team lost virtually every lawsuit it filed contesting the election results in multiple states, often in cases heard by Trump's own judicial appointees. Their rulings were littered with phrases like "without merit," "not credible," and "obviously lacking." Trump nominee Stephanos Bibas wrote a scathing opinion for a unanimous panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit, rejecting the Trump campaign's challenge to Joe Biden's victory in Pennsylvania. "Calling an election unfair does not make it so," Bibas noted. "Charges require specific allegations and then proof. We have neither here."

Even former Trump campaign lawyer Sidney Powell, who spent the fall and winter accusing Dominion Voting Systems of participating in a massive fraud that supposedly denied Trump his rightful victory, recently said "no reasonable person" would have thought her wild allegations "were truly statements of fact." In response to a defamation lawsuit filed by Dominion, Powell did not even attempt to prove the truth of her claims.

None of that stopped Republican legislators from rushing to remedy the mythical problem described by Trump and his allies. "I think what we're seeing is the most serious attempt across the country to restrict the rights of certain Americans to vote since the days of Jim Crow," said Rep. Colin Allred (D–Texas), a member of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Ohio State University law professor Edward Foley sees the legislation as an attempt to undermine the achievements of the "Second Reconstruction," when Congress passed the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964, and 1968 as well as the Voting Rights Act of 1965. "It's not exactly the same as the end of the first Reconstruction, and one has to hope that it won't be," Foley told The Washington Post. "But there are enough parallels to be nerve-racking."

The days of barring prospective Southern black voters by requiring them to count the kernels of corn in a jar or the seeds in a watermelon are thankfully over. But the spirit of those practices lives on in the recent surge of enacted and proposed restrictions on voting. Policies such as requiring a government-issued ID to vote or cutting back on early voting are facially neutral, but they disproportionately affect voters of color—who, not incidentally, overwhelmingly favor Democratic candidates.

In the past, many of the jurisdictions that are making it harder to vote would have had to clear their changes with the Justice Department or a federal court under the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That requirement applied to jurisdictions, mostly in the South, with a history of voting discrimination. But in 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated a key provision of the law, eliminating what is known as "preclearance" and ushering in a wave of voter suppression in once-covered jurisdictions that will only get worse if states pass more restrictive measures this legislative session.

Arguments about these restrictive measures often get bogged down in the question of whether particular legislators are personally motivated by racism or are merely seeking to maximize their party's share of the vote. These aren't either/or propositions, and it's hard to disentangle the two motives during these tribal times. But when legislation disproportionately erects barriers to the ballot box for certain communities—especially those that have been historically deprived of their civil rights—the lawmakers responsible for it make a mockery of the promised equality of "one person, one vote."

In states where Democrats control the legislature, these bills likely will die in committee or be voted down on the floor. But in the 19 states where Republicans control both the legislature and the governor's office, severe voting restrictions almost certainly will be enacted.

Republican legislators in these states claim they are concerned only with "election integrity" and restoring confidence in the electoral process. But a closer look at some of the legislation in Georgia, Texas, and Arizona exposes a disturbing bid to suppress the votes of people who vote blue more often than red, particularly blacks and Latinos.

Georgia

Proposed legislation in Georgia provides the most striking case study. As of February 19, according to the Brennan Center's state voting bills tracker, the state's Republican-controlled legislature was considering at least 22 bills that would selectively limit access to voting. A few caused a public firestorm because of their apparent racial bias.

Two bills sought to end no-excuse mail voting, except for older voters. That policy, which allows people to vote by mail without any special justification, was established with Republican support in 2005.

S.B. 241, which passed the Georgia Senate on March 8 but died in the House, would have allowed only voters 65 or older and those with disabilities to vote by mail. S.B. 71, which also failed, would have raised the age cutoff to 75.

These bills may seem neutral until you dig a little deeper into voter behavior in the 2020 general election. The pandemic made voting by mail an extremely popular option for all racial groups, but new patterns emerged, as my Brennan Center colleague Kevin Morris has shown.

In 2016, white voters accounted for 67 percent of the vote-by-mail electorate in Georgia. In 2020, that dropped to 54 percent, perhaps partly due to Trump's denunciations of this voting method. Black voters, meanwhile, flocked to voting by mail. They represented 31 percent of mail voters in 2020, up from 23 percent in 2016.

Last year in Georgia, about 30 percent of black voters used mail-in ballots, while only 24 percent of white voters did. White voters, however, are considerably older than black voters in Georgia. This means that, despite using mail ballots less frequently, white voters made up a clear majority of mail voters 65 years and older. By allowing elderly voters to continue to vote by mail, Republican legislators privileged their likely voters in these bills.

While allowing elderly voters to vote by mail without an excuse may look neutral at first glance, Georgia's H.B. 531 does not. The bill, which passed the House on March 1, would have eliminated Sunday voting. During election season, black churches use the day to get their parishioners to vote, a tradition known as "Souls to the Polls." The bill, which caused a public backlash locally and nationally, was recently revised. The modified measure gives local election officials the option of adding two Sundays to early voting but requires two Saturdays of early voting in the lead-up to Election Day.

The original intent was not subtle, especially when you consider that Georgia narrowly flipped blue in 2020, when President Biden won the state and two Senate races led to runoffs won by Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff. An analysis by The Washington Post's Philip Bump shows why that happened. During Georgia's early voting period, black voters accounted for 26 percent of the vote. But during the four weekend days, black voters cast 32 percent to 44 percent of the ballots. "Lock out 100,000 Democratic votes," Bump notes, "and Georgia switches from slightly blue back to slightly red."

Georgia Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan (R), breaking ranks with his party, said he understood why reasonable people would conclude that targeting weekend voting meant targeting black voters. "There is [sic] a lot of solutions in search of a problem," he told Chuck Todd on Meet the Press.

Georgia also has a history of some of the longest wait times to vote in the nation, especially in black neighborhoods. During early voting in last year's primary, voters in largely black areas waited up to seven hours to vote and drone footage showed shockingly long lines. During the general election, voters in Atlanta, which is 51 percent black, waited up to 11 hours. In response to the excruciating wait times, nonpartisan groups and good Samaritans handed out food and water to keep people in line.

This, however, is now illegal. On Friday, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp signed an omnibus voting bill that criminalized this very practice for everyone on top of other provisions that would make it harder to vote. Under previous law, the ban only applied to representatives of political organizations.

"We've had some very hot days," Savannah Mayor Van Johnson told a local news station. "So I'm supposed to watch somebody pass out and not offer them water? Or offer them food if they're diabetic or if they have some type of health challenges? Because state law says I can't help them?"

Texas

As of February 19, Texas Republican legislators had proposed at least 10 measures likely to restrict voting, according to the Brennan Center tracker. Gov. Greg Abbott has encouraged the legislation by making "election integrity" an emergency priority, even though he admitted there is no evidence yet that widespread fraud occurred in the state's 2020 election. "Republicans, of course, have run Texas for almost two decades," Christopher Hooks observed in Texas Monthly. "If there's widespread fraud in Texas elections, one would think they'd have found it by now—and fixed it."

Texas Republicans nevertheless want to make voting harder in a state already known for policies such as strict voter ID laws and cuts to polling places in rapidly expanding black and Latino communities. The state, even in the midst of a pandemic, refused to allow no-excuse voting by mail.

Harris County, which includes Houston, the state's largest city, has been a special focus of this legislative ire. The diverse city has one of the country's biggest Hispanic/Latino populations, a majority of which votes Democrat. In the run-up to the election, Harris County tried to make it easier to vote during the pandemic. Officials kept polling locations open for 24 hours to give voters more options and to limit the number of people waiting to vote. They opened drive-through voting locations, which they then almost entirely shut down on Election Day due to Republican legal challenges. And they tried to send voters mail-ballot applications but were stopped by the Texas Supreme Court.

Republicans in the statehouse want to put an end to any future experimentation with easier voting. S.B. 1115 requires all counties, regardless of size, to have the same early voting schedule. "Unless ordered by a court," the bill says, "voting time shall be not more than 12 hours in one day"—a provision that takes direct aim at Harris County.

Another Senate bill, S.B. 7, is even more restrictive. The American Civil Liberties Union of Texas summed it up in a tweet: "SB 7 would ban 24-hour voting, eliminate drive-thru voting, reduce early voting hours, and prevent counties from using stadiums and convention centers as polling places—for no reason other than keeping Texas away from the ballot box." And there's more: The bill also would require people with disabilities to provide documentation of them in return for a mail-in ballot application.

All this, Abbott says, is to ensure "trust and confidence in our elections." In December, the Houston Chronicle reported that the Texas Attorney General's Office spent 22,000 staff hours looking for voter fraud in 2020. It found just 16 incidents in which Harris County residents provided false addresses on their voter registration forms. In all these prosecutions, no one received jail time.

Also in December, an election security task force in Harris County released its report on the integrity of the November election. "Despite claims," it said, "our thorough investigations found no proof of any election tampering, ballot harvesting, voter suppression, intimidation or any other type of foul play that might have impacted the legitimate cast or count of a ballot."

Hooks' conclusion: "As with the chupacabra, voter fraud is greatly feared but rarely seen."

Arizona

Republican-controlled Arizona, whose voters broke for Biden by just 10,000 votes in November, is now also a hotbed of restrictive election legislation, including at least 22 bills according to the Brennan Center.

S.B. 1485, which recently passed the Arizona Senate, would change the rules governing the permanent early voting list, which allows the state's voters to sign up once and then receive a mail ballot for every election they're eligible to vote in going forward. The bill requires that residents on the list who did not vote in the last two election cycles be sent notices asking if they would like to continue receiving mail-in ballots. Recipients who do not respond yes would be dropped from the list, meaning that they would have to vote in person, according to the bill's sponsor.

Discussing the bill on CNN, one supporter, state Rep. John Kavanagh (R–Scottsdale), admitted that evidence of vote-by-mail fraud was "anecdotal" but argued that the legislation was necessary anyway. "Democrats value as many people as possible voting, and they're willing to risk fraud," Kavanagh said. "Republicans are more concerned about fraud, so we don't mind putting security measures in that won't let everybody vote—but everybody shouldn't be voting."

He didn't stop there. "Not everybody wants to vote, and if somebody is uninterested in voting, that probably means that they're totally uninformed on the issues," Kavanagh added. "Quantity is important, but we have to look at the quality of votes as well."

Kavanagh's observation that not everyone wants to vote is correct, of course. Libertarians, for example, often sit out multiple elections in a row simply because we don't like either major-party candidate or platform. That does not make libertarians low-quality voters. But talking about the "quality of votes" and averring that "everybody shouldn't be voting" is so reminiscent of Jim Crow rhetoric that it's difficult to be charitable and chalk those remarks up to ignorance.

Once again, the official rationale for restricting voting by mail is security. But Arizona has had no-excuse mail-in voting since 1992. Today, the vast majority of Arizonans vote by mail. During an Oval Office meeting with Trump last August, Republican Gov. Doug Ducey defended the state's vote-by-mail system. "It will be free and fair," he told Trump. "It will be difficult, if not impossible, to cheat. And it will be easy to vote."

If Republican legislators get their way, Arizona's system will be less free and less fair, and voting will be much more difficult.

What Everyone Should Want

This eruption of legislation should worry anyone who believes that the ultimate authority in this nation rests with the people and not the politicians.

Members of Congress now have a choice. They can see what Republican state legislatures are doing and consider using their power under the Elections Clause to do something about it. Republican members can put principle over party, recognizing that it may harm their electoral chances in the short term.

In a democratic nation, the vote ensures that we engage in politics, not war. It gives us a voice: one vote to cast as we please, plus the right to speak freely and convince others to also cast their ballots for particular candidates or causes. It gives us the ability to privilege the ballot box over the cartridge box when things get real. The winner today may not be the winner next election. The self-corrective process of elections allows for the peaceful transfer of power—a historical miracle that, after the Capitol riot, we might not want to take for granted.

As the internecine bloodbath of the Civil War came to a close, Frederick Douglass addressed the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in Boston. His speech, "What the Black Man Wants," is a reminder of the importance of the franchise to self-government and individual freedom.

"Without this, his liberty is a mockery," Douglass said. "Without this, you might as well almost retain the old name of slavery for his condition; for in fact, if he is not the slave of the individual master, he is the slave of society, and holds his liberty as a privilege, not as a right."

The same truth holds today. Discriminatory laws and practices that create long lines and make casting a vote as difficult as possible deter people from voting. By doing so, they attack Americans' liberty and their equality before the law. A right made onerous is, in many respects, a right denied.

Show Comments (338)