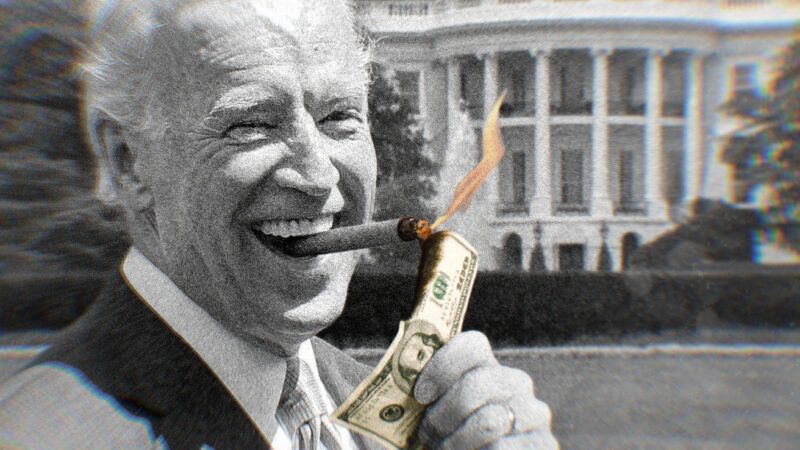

Here's How Biden's Proposed Tax Increases Will Affect You

It seems some are just waking up to the size and scope of the president's federal tax plan.

"The largest federal tax increase since 1942," is how The New York Times, in a front-page news article, is describing President Joe Biden's plan for the American economy.

The Times doesn't specify precisely how it is measuring the size of the tax increase—in terms of nominal or real dollars raised or as a percentage of gross domestic product. Whatever the yardstick, it is newsworthy.

One thing that made me chuckle is that it's only now—months after the inauguration—that the Times is waking up to the scale of Biden's tax increase plans and sharing the news with its readership at the top of its Sunday front page. This is so even though Biden was fairly open about the details of the plan during the campaign.

Some voices had even been warning about it in advance of the election.

"Read Joe Biden's Lips: New Taxes" was the headline on a July 2020 Wall Street Journal editorial.

"He has pledged a $4 trillion tax hike on almost all American families, which would totally collapse our rapidly improving economy," President Trump said in August 2020 at the Republican National Convention.

"Biden's plan to double the capital gains tax" was the headline over one blog post I wrote on the topic back in October 2020.

Why has reaction, at least so far, been relatively muted?

The pandemic, the Black Lives Matter protests, and the January 6 political violence all distracted from the tax issue.

The radical nature of the Democratic primary field—Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) both favored a wealth tax—made Biden's tax increases, while vast, seem more moderate by comparison.

And while Biden's tax plans add up to a hefty hit overall, some of the pieces themselves seem incremental.

He'd increase the top corporate rate to 28 percent. That's more than the current 21 percent, but still less than the 35 percent that applied between 1993 and 2017.

He'd increase the top individual income tax rate to 39.6 percent. That's up from the current 37 percent, but it's a rate that applied from 1993 to 2000 and again from 2013 to 2017, so it's not exactly unknown ground.

The two most extreme aspects of the Biden tax plan each have political pitches behind them that are at least plausible. The 12.4 percent payroll tax for Social Security's Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance is capped for 2021 on a wage base of $142,800. Biden would apply the tax to income above $400,000. That, not the increase to 39.6 percent from 37 percent, would be the real hit to high-income earners in the Biden plan. The combined effect—39.6 percent plus 12.4 percent—would be that at the margin, the federal government would take 52 percent, or more than half, of dollars earned over $400,000. There's an additional Medicare tax of 3.8 percent, which would take the top federal marginal tax rate up to 55.8 percent.

To my mind, it's just on its face unjust for the federal government to take more than half of what anyone earns.

The political explanation of this by the Democrats, though, is the combination of "bring back the top individual rates that we had under Clinton and Obama, when you all did pretty well" and "it's unfair for Warren Buffett to pay a lower tax rate than his secretary," which is partially a function of the current cap on the base for the Social Security payroll tax.

The other big piece of the Biden tax increase is a plan to bring the capital gains tax rate up to the earned income tax rate. Biden campaigned on that: "I think it's about time we start rewarding work in this country, not wealth," he said. "I think it's time working families get a break and the super wealthy and big corporations pay their fair share. They're still going to be doing just fine." Toward the end of the Reagan years, 1988 to 1990, the top capital gains rate, 28 percent, and the top income tax rate, 28 percent, were one and the same, so this idea, too, isn't entirely unprecedented.

Opponents of a capital gains rate increase point out that it's partly a tax on inflation, as the government finds a way to tax homeowners or stock owners on the government's own failure to maintain a currency that is a stable store of value. They also argue that it's double taxation, as money that produces capital gains has often already been taxed once as income at either the corporate or individual level. Such taxes punish risk-taking and investment, and discourage capital formation.

The arguments about taxation are familiar at this point from being carted out each time a new presidential administration arrives and seeks to reset the rates.

Democrats argue that spending funded by the taxes will contribute to more vigorous and widely distributed growth, reducing inequality.

Republicans argue that the money is spent more wisely by individuals or firms than by politicians, that there is an injustice in a majority ganging up to take away money from hardworking people who have created value, and that the increased taxes will reduce incentives and slow growth.

The debate may feel stale, but as a political matter, it is unresolved. The recent pattern has been that Democrats overreach and raise taxes to the point where Republicans get annoyed and lower taxes. Then the cycle repeats again.

Show Comments (131)