Why Use Two Doses of COVID-19 Vaccines When One Works Almost as Well?

We could double the number of Americans vaccinated against COVID-19.

With the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine already cleared and the Moderna vaccine soon to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), COVID-19 relief finally seems to be on the way. There remains the issue of distribution, and as it stands, rollout will not be completed until summer. But Duke data scientist Zeynep Tufekci and Harvard epidemiologist Michael Mina point out in a recent New York Times op-ed that changing the vaccines from a two-dose to a one-shot regimen would double the number of Americans who could be vaccinated soon, all without losing a significant amount of protection against COVID-19 infection.

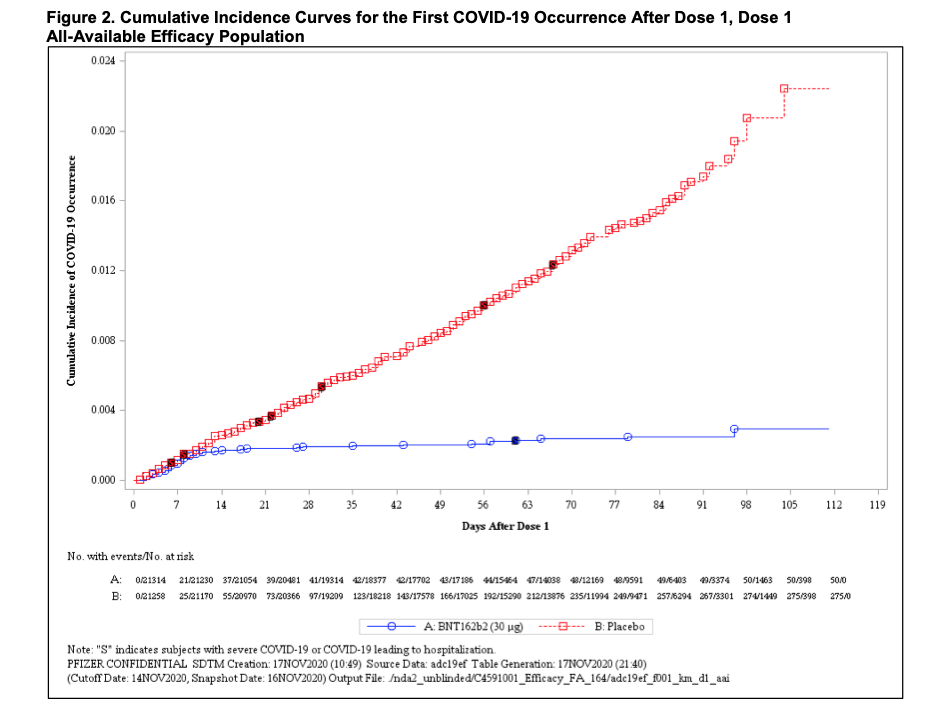

Tufekci and Mina note that infections dropped off steeply after two weeks among the participants in clinical trials who were inoculated with the first dose of the vaccines. Preliminary data from the Pfizer/BioNTech trial suggested that the vaccine efficacy for the prevention of COVID-19 was 82 percent after the first dose. Efficacy against severe COVID-19 occurring after the first dose was 88.9 percent. In comparison, the two-dose regimen is 95 percent effective against infection.

The Moderna vaccine, according to preliminary clinical trial data, provides substantial protection after the first dose as well. Tufekci and Mina note, "Moderna reported the initial dose to be 92.1 percent efficacious in preventing Covid-19 starting two weeks after the initial shot, when the immune system effects from the vaccine kick in, before the second injection on the 28th day." The Moderna vaccine is 94.5 percent effective after the second dose.

Back in June, the FDA issued guidance outlining the agency's expectation that a COVID-19 vaccine would prevent disease or decrease its severity in at least 50 percent of people who are vaccinated. According to preliminary data, one dose of either the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna vaccines clears this low hurdle.

Tufekci and Mina note that important questions remain, namely how long immune protection may last. But even if immunity were to wane over, say, a year, that would still provide enough time for people to get a booster shot later this year while the initial one-dose inoculation protects people immediately. Tufekci and Mina suggest that clinical trials evaluating one-dose efficacy could be rolled out quickly among low-risk healthy younger health care and essential workers.

I appreciate their caution, but given the much lower 50 percent vaccine efficacy threshold set by the FDA in June, the benefits of adopting a one-dose strategy using these vaccines outweigh the current real risks of the rising pandemic.

In any case, they are not wrong when they assert, "The possibility of adding hundreds of millions to those who can be vaccinated immediately in the coming year is not something to be dismissed."

Show Comments (129)