The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Circuit Court Nominations and Senate Obstruction

It is rapidly becoming a talking point among some activists on the left that Mitch McConnell busted all norms in obstructing Barack Obama's circuit court nominees, and thus it is only fair that the Democrat pack the Court at the earliest opportunity. (Let us save for another day the other trending claim, fed by Joe Biden himself, that filling ordinary judicial vacancies is itself a form of court "packing" indistinguishable from expanding the size of the Court.)

President Donald Trump has not helped matters by repeatedly bragging that Obama left "a big, beautiful present" of judicial vacancies. Critics of Trump's judicial appointees have been quick to answer that the only reason those vacancies exist is because of Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell's unprecedented obstruction of Obama's nominees.

In truth, Trump inherited a number of vacant circuit-court seats that was only slightly larger than what Obama inherited (Trump did inherit significantly more district court vacancies). If Obama left him a "big, beautiful present," Bush left the same present for Obama. Bill Clinton inherited a comparable number of vacancies when he was first inaugurated, though George W. Bush was somewhat more fortunate. Trump inherited far more open seats than did Ronald Reagan, but otherwise he found himself in much the same position as recent presidents. Neither Trump nor Obama were unique. They were reflective of what judicial appointment politics have looked like for the last three decades.

There is endless finger pointing in the war over judicial appointments that gets in the way of any effort at potentially deescalating what is a very unhealthy situation. There is plenty of bad blood and hurt feelings on both sides, and there is little to be gained by trying to determine who hurt whom first.

But we should at least be clear that Obama was not uniquely mistreated in regard to his circuit court appointments (the question of Merrick Garland is a separate issue, but Garland seems to be becoming a mere symbol of general obstruction of judicial nominees). The problem of Senate obstructionism was not a two-year anomaly in 2014-2016 (though those two years were an extreme version). It has been far more deep rooted and persistent than that.

There is no question that Donald Trump has benefited from the combination of a relatively large number of open seats in the lower courts, procedural reforms that made it possible for the Senate to confirm judges on a simple majority basis (starting when Democratic leader Harry Reid nuked the filibuster in 2013), and same-party control of the Senate (the Democrats promptly lost control of the Senate in 2014 and so had little opportunity to take advantage of the new rules). As a result, Trump has been able to appoint a relatively large number of circuit court judges in a single term. He would not have been able to do so had not all three things been true.

Details on circuit court nominations and confirmations over the past forty years below.

As I have detailed in a paper that can be found here, the obstruction that Obama encountered for his lower court nominations had become par for the course over several presidencies of both political parties. Trump found a lot of vacancies on the circuit courts because the Senate had not allowed presidents to fill available seats -- and they had done so not merely in the last two years of Obama's presidency under a GOP Senate. The Senate had done so for nearly a quarter of a century.

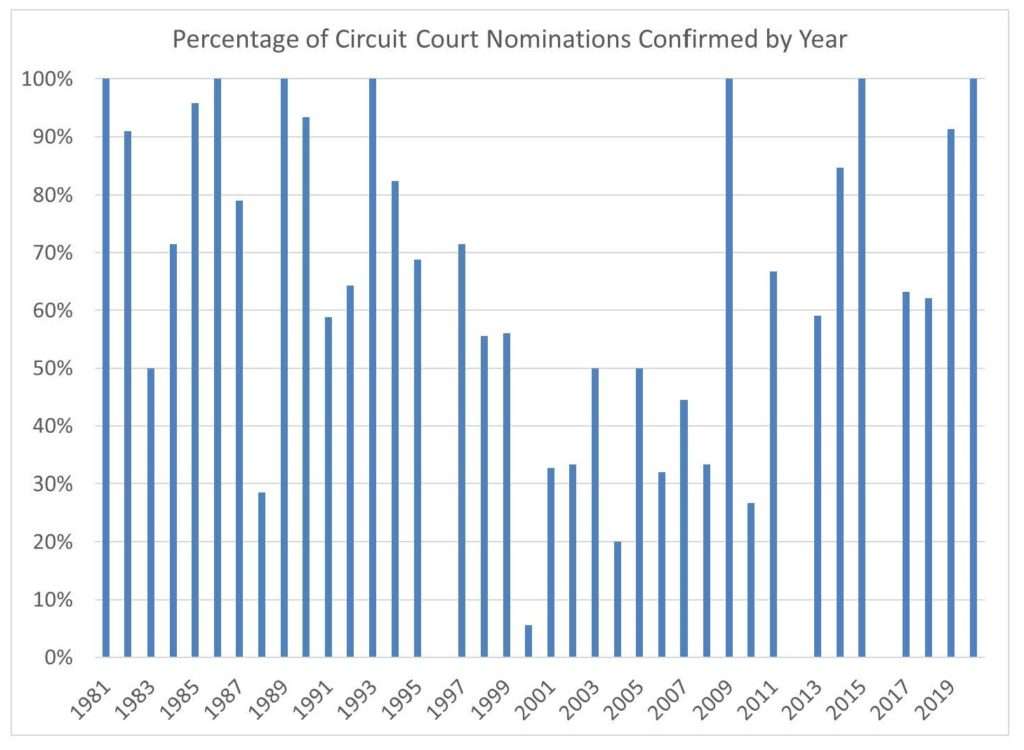

As the above figure shows, there has been a fair amount of variation in the percentage of circuit court nominations that result in a confirmation since the beginning of the Reagan administration in 1981. Presidents predictably have more trouble getting their nominees confirmed when the other party controls the Senate and they particularly tend to struggle when a presidential election looms. (Notably, circuit court nominations are hardly ever defeated in a floor vote; unsuccessful nominations are either returned or withdrawn.)

But things have been different since the Clinton era. Presidents of both parties have found their nominations stymied by senators of the other party. It has taken much longer to get a nominee confirmed. More nominees fail to ever reach the bench. Presidential behavior matters as well as Senate behavior. Some presidents flood the Senate with nominees, and others do not (Obama had few successful appointments in his last years in office but he also made very few nominations. Even when Obama enjoyed a Democratic-controlled Senate, he advanced relatively few nominees. Despite having a Democratic Senate, Obama began his second term of office with as many judicial vacancies as when he first arrived in the White House.). Some presidents return nominees to the Senate over and over again, and others pull the plug when nominees get bogged down.

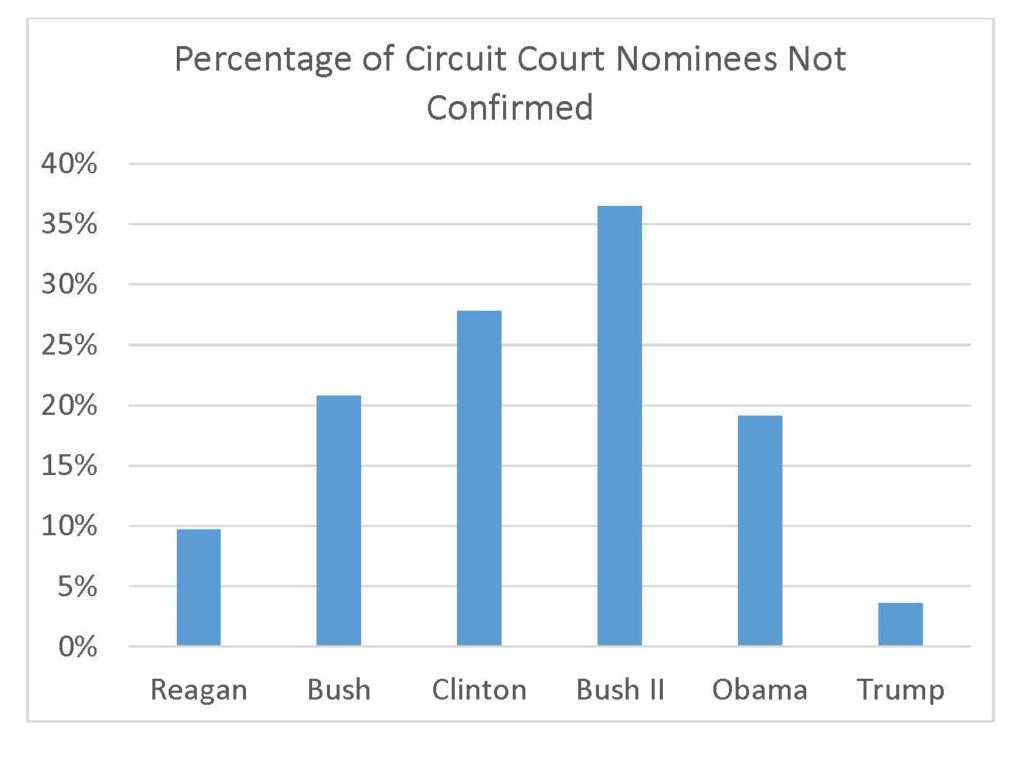

We get a somewhat different picture of recent developments if we focus not on individual nominations but on individual nominees. Unsuccessful nominees to the circuit courts do not get a floor vote; they are just left dangling in the wind. Given the delay in confirming, some nominees who are eventually successful go through several nominations. If we track the fate of particular individuals to their final fate, we see an increasing obstruction by the Senate that peaked in the George W. Bush administration. Over a third of the individuals put forward for a circuit seat by Bush were not confirmed by the end of his presidency. No other president has had such a dismal record. Obama's overall record was good by comparison.

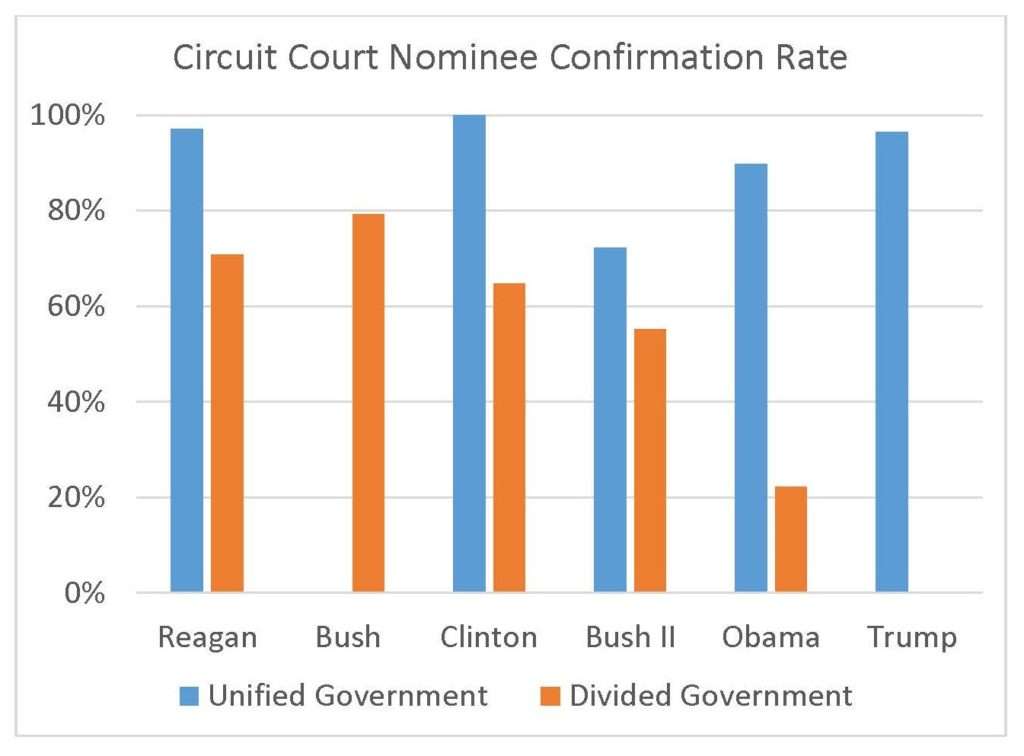

When we focus on individual nominees (rather than nominations, as I did in the paper here), divided government appears to be a significant culprit. George W. Bush had extraordinary struggles putting nominees on the bench even with a Republican majority in the Senate as minority obstruction peaked. He did even worse with a Democratic-controlled Senate, which was even less willing to confirm his nominees that the Republican-controlled Senate had been with Bill Clinton. Obama enjoyed a Democratic Senate for most of his presidency, and his success rate was quite high (though not quite at historical expectations). When Obama lost the Senate in the last two years of his presidency, however, his success in seating circuit court nominees ground to a halt. Opposition Senates were likewise hard to please at the end of the Clinton and Bush presidencies, but Obama's success rate was low even by those standards.

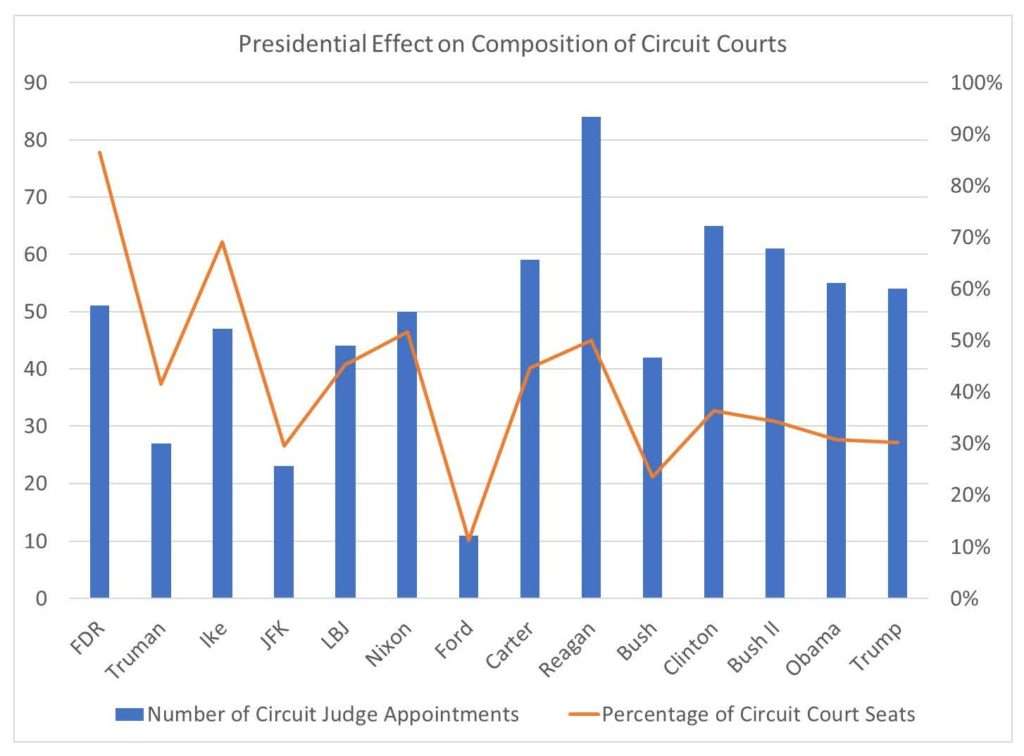

At the end of the day, recent presidents have been able to seat a sizable number of circuit court judges. Donald Trump likes to brag that he has seated an unprecedented number of federal judges, and he has done quite well for a single presidential term. But he has seated fewer circuit-court judges who in turn make up a smaller percentage of the federal bench than did the one-term president Jimmy Carter, who benefited from not only an accommodating Senate but also an expanded judiciary. If he is defeated in November, he will have left a mark on the circuit courts that is comparable to what Obama left, and only slightly less than what Clinton and Bush left.

Senate obstructionism has been a pervasive problem for decades. The Senate reached new lows of obstruction over the last two years of the Obama presidency, but it was the continuation of a trend not a sudden departure. If the Senate Republicans had been willing and able to do the same thing earlier in the Obama presidency or at the start of a Hillary Clinton presidency, then it truly would have been an extraordinary sea change in interbranch relations (even by modern standards), but those circumstances never arose. What seems apparent is that Trump has enjoyed the same kind of confirmation success that most presidents enjoy with same-party Senates. Unfortunately, there is little reason to think the recent trends would have reversed themselves had he faced an opposition Senate.

We might have solved the confirmation dysfunction for unified government, but the dysfunction that has recently prevailed during divided government seems likely to still be with us.