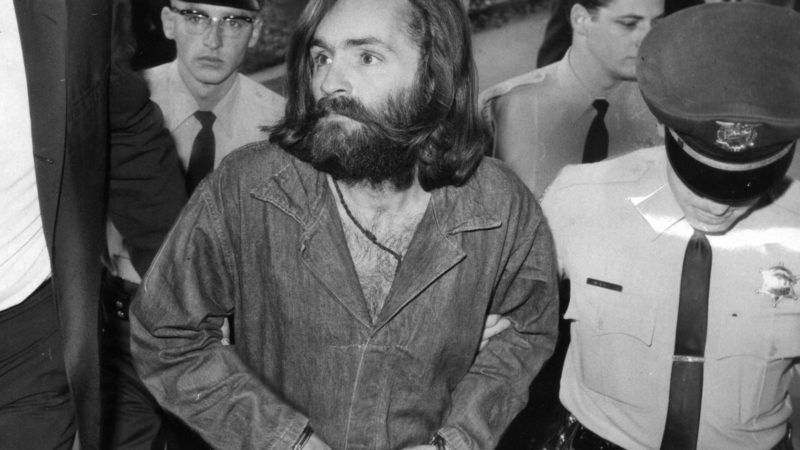

A New Charles Manson Documentary Series Pulls All the Disturbing Threads Together

Helter Skelter: An American Myth doesn’t shed new light, but it’s excellent journalism.

Helter Skelter: An American Myth. Epix. Sunday, July 26, 10 p.m.

I'm happy to report that the publicity campaign for Epix's documentary on the Charles Manson murders, Helter Skelter: An American Myth, is a mendacious hoax. "You think you know the story. … You don't," scream the ads. "It will upend what people think they know about this layered and complex story and cast an entirely new light on this Crime of the Century." Coupled with the provocative word "myth" in the title, it sounds like a batty revisionist history of seven murders that are not only among the grisliest in American history, but the most well-documented.

Why the show's publicists took this strange direction, I have no idea. But they couldn't have been more misleading. The six-part Helter Skelter: An American Myth is the most comprehensive documentary on Charles Manson and his pathological family, the most thorough, and the most fascinating. It's excellent journalism and great television.

But unless you're a drooling Manson apologist—and, God help us, they exist—American Myth won't change anything you think about the murders or the people who committed them, except possibly to make you love the flamethrower scene in last year's anti-Manson fantasy Once Upon a Time in Hollywood even more. (The precise moment that will happen: Near the end of the fourth American Myth episode, when the soundtrack goes deadly silent, and the screen flashes unexpurgated scenes of the crime scene at actress Sharon Tate's home.)

If you're wondering why the Manson story, already the subject of countless books, films and TV shows, needs another retelling, that's a reasonable question. Little new has emerged since Manson prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi and his co-author Curt Gentry released their account of the case, Helter Skelter, in 1974.

But the Manson Family story continues to resonate. As several of the figures in the case interviewed in American Myth note, most of us probably can't name the perpetrators of the crazed massacres at Virginia Tech or the Pulse nightclub, even though they were committed much more recently and at much greater loss of life. Yet the name Charles Manson remains macabrely familiar a half-century after his crimes.

Part of the reason, undoubtedly, is that Manson's conversion of a group of sappy flower children into a band of truly crazed killers who could wreak "incomprehensible slaughter of innocent people," as one reporter who covered the case describes it, abruptly ended the peace-and-love mythos of the 1960s.

And part of it is that Manson was neither a lone nut nor a troubled man who suddenly cracked one day. He nurtured his evil designs over a period of years, and infected a group of otherwise innocent people with them. He is probably as close to the personification of evil as has ever walked the streets of America.

American Myth does a good job of covering the broad outlines of Manson's story: His early life in reform school and prison, his release into the toxic stew of drugs and runaway kids in San Francisco in the mid-1960s, and—like the physical incarnation of parental fears—his use of hallucinogens, group sex, and all-is-groovy freethink to gather a following. And, of course, the savage murders of Sharon Tate and at least eight others.

But it's in the forgotten and often trivial details that the show gains an irresistible momentum. Long interviews with Manson biographer Jeff Guinn and three former Family members—genuine hippie Catherine (Gypsy) Share, hot-to-trot teeny-bopper Dianne (Snake) Lake, and itinerant musician Bobby Beausoleil—make up the core of the narration. And producer-director Lesley Chilcott (Waiting for 'Superman') has also amassed an absolute mountain of archival material, from tapes of Manson's musical tryouts at Hollywood studios to home movies from Family members.

The result is something like dinner around the fireplace with the world's foremost Manson authorities: How the Family ran up a $1,200 bill with the milkman at Beach Boy Dennis Wilson's house. Manson cutting up Wilson's silk sheets to make himself a pair of baggy harem pants.

Hilarious footage from a 1967 tour bus carrying middle-class passengers on a safari through Haight-Ashbury as they study a dictionary of hippie-speak that identifies the local flora and fauna. ("Spade cat: Negro hippie.")

The grave voice of a TV newsman describing "a group of compatible hippies, sharing their rice and beans and hepatitis and venereal disease." A tape of one of Manson's demo recording sessions, where a producer can be heard exclaiming, "Hi, Charlie Baby! Do whatever you feel like!", words that might have curdled in his mouth if he'd known who he was talking to.

There's even a tape of an interrogation of Sharon Tate's husband, director Roman Polanski, by Los Angeles police officers. "I'm looking for something which doesn't fit your habitual standard," Polanski tells the baffled cops. Translation: He thought someone from the couple's Hollywood circle of friends was the killer. He first suspected martial arts star Bruce Lee (who else could kill so many people single-handedly) and then Mamas and Papas singer John Phillips (whose wife Michelle had a one-night fling with Polanski). For months, Polanski snuck into garages of his friends and tested possible blood spots in their cars.

It is in the motives for the murders of Tate and her friends—and, a couple of days later, of grocery-chain owner Leno LaBianca and his wife Rosemary—that American Myth gets contentious.

The generally accepted theory, the one prosecutor Bugliosi unveiled in the trial where he convicted Manson and three of his female followers of murder, is that Manson believed he was following instructions that the Beatles sent him embedded in the songs of what's known as the White Album.

Manson said the songs, particularly the violent "Helter Skelter," predicted a race war in America in which blacks would emerge triumphant. But the Family could survive in a cave in the desert, Manson said, and emerge to help steer the resulting black-administered society.

That Manson preached the "Helter Skelter" doctrine incessantly is beyond question. The question is, did he believe it? Or was it just one more manipulation of his followers

Bugliosi, who acknowledged Manson's frequent trickery but also thought he was fairly crazy, thought he believed it and ordered the murders to trigger the race war he was certain was coming. Guinn, Manson's biographer, thinks the whole thing was a shtick to hold onto Charlie's increasingly restive followers: "So do you wanna die? Or do you wanna come with me and rule the world?"

The outcome of this debate matters little except among the fiercest Manson aficionados, and now that Manson's dead, it's impossible to resolve. Most of the Family members interview in American Myth think he believed it.

I've got no idea, but having interviewed the late Bugliosi several times as a reporter—about Manson as well as other criminal cases—I'm inclined to believe anything he said about the Family, on which he was unquestionably the world's greatest expert. The first time we talked, I told him: "Your book scared the hell out of me." He replied: "It should have." Helter Skelter: An American Myth will remind you why.

Postscript: I also met Charles Manson, sort of. We were mutually unimpressed.

Show Comments (45)