The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Two Reflections on the American Revolution

I recapitulate why it's important that the American Revolution was not an ethno-nationalist secession movement, and address claims that history would have taken a better course had the Revolution been defeated or never happened.

Today is July 4, Independence Day. In previous years, I used this opportunity to address two important aspects of the Revolutionary War that are sometimes neglected. Both issues remain relevant today.

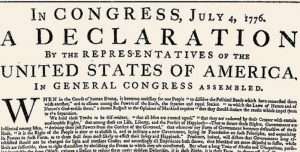

In this 2017 piece (see also updated version here), I explained why it matters that the Declaration of Independence did not justify secession from the British Empire on the basis of ethnic nationalism, but rather based on universal principles of human rights, which the British government had violated:

As I noted elsewhere in the same piece, the revolutionaries themselves often failed to live up to the high principles they asserted, most notably in so far as many of them were slaveowners. But that doesn't mean the Declaration's principles were useless, even when it comes to the issue of slavery:

Despite our many deviations from them, it would be a mistake to assume that the Declaration's ideals were toothless. Even in their own time, the principles underlying the Declaration helped inspire the First Emancipation – the abolition of slavery in the northern states, which came about in the decades immediately following the Revolution. This was the first large-scale emancipation of slaves in modern history, and it helped ensure that the new nation would eventually have a majority of free states, which in turn helped ensure abolition in the South, as well.

The Declaration did not abolish slavery, and its high-minded words were, for decades, undercut by the hypocrisy of Jefferson and all too many others. But the ideals of the Declaration played an important role in slavery's eventual abolition.

That brings us to the topic I considered in a post written on Independence Day last year: "The Case Against the Case Against the American Revolution." In that piece, I addressed arguments from both left and right suggesting that the world would be a better place if the Revolution had been defeated or had never occurred at all:

July 4 is almost over. But there is still time to address claims that history would have taken a better course had the American Revolution failed (or never started). In the United States, such arguments are made mostly by people on the left. This 2015 Vox article by Dylan Matthews is an excellent example. But similar claims are also made by a few libertarians, such as my George Mason University colleague Bryan Caplan, and by some Canadian and British conservatives. Here are the main arguments typically advanced by modern critics of the Revolution…..:

1. British rule would have led to an earlier and less violent abolition of slavery. The British Empire abolished slavery in 1833, some thirty years before the United States, and it did not require a bloody civil war to do it.

2. A British-ruled America would have treated Native Americans better (as witness their apparently superior treatment in Canada).

3. A British America would have had a parliamentary form of government rather than separation of powers, which—among other advantages—would have led to a larger welfare and regulatory state. This latter point, of course, is usually made by left of center critics of the Revolution, not conservative and libertarian ones.

4. The history of Canada (and later Australia and New Zealand) shows that the British Empire was capable of gradually granting colonies increased autonomy and rights without the need for a bloody revolt.

5. The Revolutionary War caused enormous bloodshed. Some 25,000 Americans died (a larger percentage of the population than were lost in any of our other wars, besides the Civil War). To that figure, we should add numerous casualties suffered by British and French troops, and by German mercenary soldiers hired by the British. The possible gains of the Revolution were not enough to justify this terrible loss of life.

It's a weighty indictment we should take seriously. But in the rest of the post I explain why it is nonetheless mostly wrong. Despite the very real flaws of the revolutionaries and of the new nation they founded, the world is a better place thanks to their sacrifices.

Appropriate recognition of the achievements of the Revolution should not, however, blind us to the many ways in which we still fall short of the ideals it espoused. The present US government is guilty of many sins, including some that reminiscent of the ones that the Declaration condemned. Too often, it still fails to protect life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and still fails to treat all persons equally, regardless of morally irrelevant characteristics such as race, ethnicity, and circumstances of birth.

Abraham Lincoln's 1857 statement on the meaning of Declaration of Independence remains appropriate today:

I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects…. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality, or yet, that they were about to confer it immediately upon them…

They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit.

They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society which should be familiar to all: constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even, though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, everywhere.

Show Comments (64)