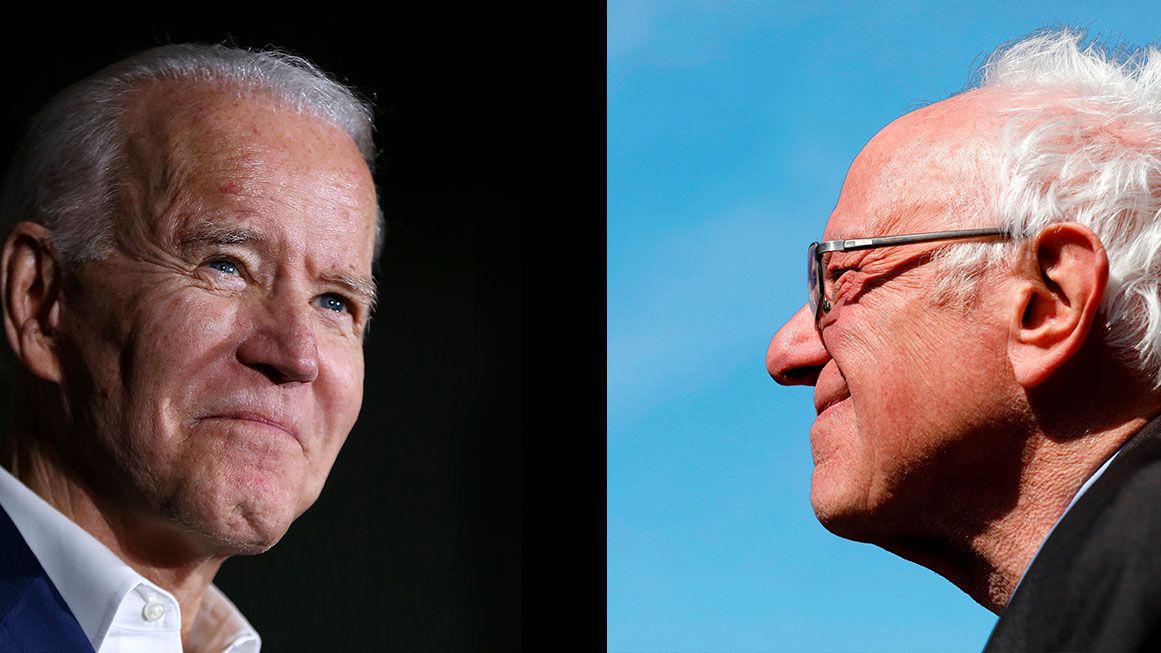

Joe Biden Won the Democratic Primary. But Bernie Sanders Won the Party.

Two weeks before ordinary American life was completely upended by COVID-19, Joe Biden had effectively captured the Democratic primary nomination with a campaign that amounted to a single promise: a return to normalcy.

In his 2019 announcement speech, Biden had emphasized national unity and "common purpose." He wanted to defeat President Donald Trump and move past the polarized squabbling and dysfunctional governance that had become the norm under his administration. "Our politics has become so mean, so petty, so negative, so partisan, so angry, and so unproductive," he said. "So unproductive. Instead of debating our opponents, we demonize them. Instead of questioning judgments, we question their motives. Instead of listening, we shout. Politics is pulling us apart."

A year later, after consolidating his lead on Super Tuesday, Biden delivered an exuberant victory speech in Philadelphia, promising to unite his own party and defeat Trump. As he had throughout his campaign, he offered a nostalgic appeal to shared identity, to national values and character. "Folks," he said, "we just have to remember who we are." More than anything else, he wanted to get back to the way things used to be.

Officially, Biden hadn't yet clinched the nomination at that point: His chief antagonist, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.), would remain in the race for another month, continuing to attack the former vice president as insufficiently committed to the socialist revolution he thought was necessary to fight the virus. But Biden had won a commanding lead where it counted, in the race for convention delegates. Just weeks before, Sanders had looked like a shoo-in. But after the votes were cast in South Carolina and on Super Tuesday, the Vermont socialist didn't have a chance.

The primary had been a slog featuring more than 20 candidates, and at various points several had looked like plausible winners. But in the end, it was probably inevitable that it would come down to the two men who initially led the polls, and who represented the twin poles between which the increasingly divided party existed.

At one end was the cranky, consistent, discontented democratic socialist: Sanders, an independent, was an outsider within the party he sought to lead, a committed ideologue with fervent policy preferences. A lifelong critic of the milquetoast Democratic establishment and its get-along tendencies, he campaigned on revolution, on an overthrow of the current order.

Biden, in contrast, was the ultimate party insider, a man first elected to the Senate at the tender age of 29 who had weathered life-altering tragedy and controversy from within its shelter. He had policy views, but mostly he championed compromise and bipartisan deal making. Over the course of more than 40 years in politics, Biden had become a kind of avatar of the Democratic Party, the figurehead of its establishment.

The primary race had been a contest between the Democratic Party's biggest champion and its most prominent critic on the left—and the party champion had emerged victorious.

Looked at one way, Biden had won not only the primary race but an intraparty argument over its future. There would be no revolution. Socialism would be held at bay. The establishment would continue its reign. Everything would return to normal. That was the promise.

Looked at another way, however, Biden's win was far from decisive, less a clear victory over the forces of socialism and more a temporary stalling measure that accepted a lethargic version of the Democratic Party's leftward demographic trajectory and bought into many of the underlying assumptions of democratic socialism, if not the explicit label. Sanders appeared to have lost the race, but he may have won the better part of the argument—and the future of the party.

And then there was the coronavirus, which originated in China at the end of 2019 and began wreaking havoc on the American economy just as Biden settled into his role as the presumptive Democratic nominee. The pandemic arguably elevated Biden's appeals to competence, stability, and good governance. But it also threatened to undermine the central argument of Biden's blandly nostalgic campaign.

For in a world of unprecedented uncertainty, with the global economy hushed by a pandemic, what would it mean to return to normal?

The Sanders Challenge

Even before it started, the Democratic primary looked like a two-man race. And that race neatly illustrated the party's essential divide between establishment continuity and socialist revolution.

In the early months of 2019, polls showed Biden with a clear lead among Democratic voters, which, if nothing else, reflected the former vice president's strong name recognition. The question was whether name recognition alone would be enough.

Biden had run for the nomination twice before, in 1988 and 2008. Both times he had flopped, dropping out after a plagiarism scandal in the first race and after a dismal fourth-place finish in Iowa in the second. In 2019, after four decades in Democratic politics, Biden was broadly liked and even admired by many in the party. But his support lacked intensity, and relative newcomers such as South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Sens. Kamala Harris (D–Calif.) and Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) challenged his command of the party faithful in different ways.

Sanders had the opposite problem. He had proven a surprisingly strong opponent against Hillary Clinton in 2016, and he had amassed a base of almost fanatically devoted supporters who shared his critique of the party establishment. But those fans had also gained a reputation for hostility, even and especially toward his Democratic rivals, making him a polarizing choice. For Sanders, then, the challenge was breaking out of his own bubble of fandom.

Yet Sanders had a model in the similarly polarizing, similarly noxious 2016 campaign of President Donald Trump.

In the run-up to the race, Sanders' team was blunt about the way his strategy echoed Trump's. A 2018 profile in New York summarized the approach as follows: "Facing what's likely to be a historically large field, he's been told, Sanders could start with his most loyal supporters from last time and go for a tight plurality victory in Iowa's caucuses, followed by a slightly bigger one in New Hampshire's primary. From there, advisers hope, his numbers could grow as the field dwindles."

Like Trump, Sanders was a rabble-rousing populist, an anti-establishmentarian who inspired devotees dissatisfied with the political status quo. Like Trump, he planned to win by exploiting pre-existing intraparty divisions and a particularly crowded field. And like Trump, Sanders would soon expose the deep rifts within his own party in the process.

Sanders was running as a democratic socialist who favored massive expansions of federal welfare and entitlement programs that went far beyond the party consensus. He found his strongest support among those frustrated by that consensus and the limits it imposed on them.

The intensity of the divisions exposed by his campaign suggested that the Democratic Party wasn't really one party. It was two, divided largely by age and, to a lesser extent, education.

Like Biden, Sanders was in his late 70s. But he was the candidate of the young. Where Biden's support among young voters was all but nonexistent, Sanders led the field among that demographic in every poll. In November 2019, pollsters at Quinnipiac University asked voters which candidate had the best ideas. Among those under 35, 27 percent favored Sanders; just 4 percent preferred Biden.

In addition to being younger, Sanders supporters were more militant and more favorable to his brand of socialism. Radicalized by the financial crisis and the Great Recession, they were, in some sense, a party unto themselves. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Sanders campaign reflected their concerns, most of which revolved around the affordability of middle-class essentials: housing, education, and, most of all, health care.

For years, Sanders had called for Medicare for All, a single-payer system in which the government would finance virtually all health care in the country, which multiple independent analyses estimated would require between $30 trillion and $40 trillion per decade in new federal spending. In the process, the plan would make virtually all existing private health insurance illegal.

Arguments about how to finance the plan, and about whether it went too far in outlawing private coverage, chewed up large chunks of the Democratic primary debates. Biden repeatedly attacked Sanders for the plan, arguing that it would deprive people of choice, unfairly harm union members who had negotiated generous health benefits, and be prohibitively expensive to taxpayers. He favored building on Obamacare with a pricey but comparatively modest expansion of the program.

More than any other issue, the debate over Medicare for All exemplified the party divide: Biden wanted to spend $750 billion to expand Obamacare by adding a government-run insurance plan to the mix; Sanders staked his campaign on spending $30 trillion to blow away the nation's entire health care financing infrastructure. To say that the Sanders wing of the Democratic Party was really just a Medicare for All party would be an exaggeration—but one with a degree of truth.

Sanders supporters often seemed aware of the gap between their vision for the party and the vision of those at its power centers. "In any other country," said Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D–N.Y.), an outspoken Sanders backer and perhaps the most prominent of the young democratic socialists, in January, "Joe Biden and I would not be in the same party."

Sanders, the lifelong independent who had a habit of praising authoritarian leftist regimes—in February, he answered a question about Cuba by applauding Fidel Castro's literacy efforts—was, at heart, a revolutionary. And he was staging a party takeover.

It almost worked. After a botched count, Sanders nearly tied for first place in the Iowa caucuses, and he followed that by winning clear victories in New Hampshire and Nevada, where he bested Biden by more than 26 points. Biden, meanwhile, had weak showings in all three initial contests.

The Sanders campaign's Trump-like strategy—divide the party to keep voters from consolidating around any one rival—seemed to be succeeding. "This was a big, impressive win for Sanders," wrote election analyst Nate Silver of the website FiveThirtyEight after the Nevada results, "and it should be even clearer now that Sanders is easily the most likely Democrat to win the nomination." Biden was losing; Bernie was winning. The socialist revolution was nigh.

Just Biden His Time

That Biden was losing the Democratic primary race wasn't much of a surprise. He had run twice before and never made it past the Iowa caucus. Joe Biden was nobody's idea of a president—except, perhaps, Joe Biden's.

Biden won his first Senate race just before his 30th birthday, making him one of the youngest individuals ever elected to the chamber. During his first term, he was asked about his ambitions for higher office. "I have no desire to run for those offices," he said of himself at the time, according to Jules Witcover's biography, Joe Biden: A Life of Trial and Redemption. "But I'd be a damn liar if I said that I wouldn't be interested in five, 10, or 20 years if it were offered." Biden wanted to make an impact on the nation, he continued, "and there is no place you can have greater effect than as president. So you're being phony to say you're not interested in being president if you really want to change things."

But Biden never quite became the agent of political change he so clearly desired to be. He was, in colloquial terms, a swamp creature, a permanent fixture on the Washington scene, the sort of politician whose career inevitably includes a variety of serious and not-so-serious scandals, from plagiarism to allegations of sexual misconduct to family members profiting off his political connections. Simple, stupid gaffes seemed to plague Biden, who loved nothing more than gabbing.

Biden was a senior Democratic lawmaker. But he wasn't really a party leader. He was a loyalist, an operator, a backup man. He didn't tell the party where it should go. He revealed where it had already gone.

In the 1970s, that meant insisting that President Richard Nixon receive fair treatment, even from his political opponents—and then, inevitably, concluding that Nixon must either resign or be impeached. It meant opposing the war in Vietnam but also opposing amnesty for draft dodgers. It meant reaching out to young voters but rejecting the legalization of marijuana. And it meant walking a fine line on issues of race—positioning himself as a champion of civil rights even while objecting to mandatory busing to integrate public schools, which he called "a phony issue which allows the white liberals to sit in suburbia, confident that they are not going to have to live next to blacks."

"When it comes to civil rights and civil liberties," he told Washingtonian in 1974, "I'm a liberal, but that's it. I'm really quite conservative on most other issues."

In the 1980s, Biden served as the lead Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee and played a pivotal role as the party's floor manager during Congress' passage of the Comprehensive Crime Control Act. That law would be a centerpiece in the federal war on drugs, expanding criminal penalties for marijuana and giving the Justice Department the authority to seize cash and assets suspected of being related to illegal drug sales.

In a 1991 speech on the Senate floor, Biden lavished praise on the law for its harsh treatment of suspected dealers. "We changed the law so that if you are arrested and you are a drug dealer," he said, "under our forfeiture statutes…the government can take everything you own. Everything from your car to your house, your bank account. Not merely what they confiscate in terms of the dollars from the transaction that you've just got caught engaging in. They can take everything."

The law removed judicial discretion from sentencing, Biden went on to note. Three years later, he backed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which funded 100,000 new police officers, expanded the death penalty, set up a registry for sex offenders, and implemented a federal ban on firearms deemed "assault weapons." All this was justified with rhetoric about the war on crime and the war on drugs.

Eventually, Biden moved on to defending actual wars, including the NATO's intervention in Bosnia and the U.S. bombing of Serbia in 1999. After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, he supported the war in Iraq—but he opposed the 2007 troop surge, which came after initially high public support for the war had dwindled.

As Barack Obama's vice president, Biden played a similar role. He served as the administration's point person for multiple negotiations with Congress over the budget and oversight of the $850 billion stimulus program passed after the financial crisis.

In his decades in the Senate and his years outside the Oval Office, Biden repeatedly found himself near the party's center of gravity. Almost invariably, wherever the Democratic establishment was, there too was Joe Biden—often in a prominent capacity. Like Forrest Gump, he somehow always managed to be in the thick of things.

Biden's career was a guide to the party's shifting priorities and predilections, which meant it was also a guide to its many, many offenses and mistakes. Almost invariably, when the Democratic Party was wrong, Biden was there to demonstrate just how wrong it was, embodying its most ill-advised tendencies on war, crime, drugs, the courts, and more. Biden's career was one long litany of Democratic establishment failures.

So when he decided, at the age of 76, to make a third run for president and to build his campaign on nostalgia for an earlier era, one might have been tempted to ask: Nostalgia for what?

Except that Biden wasn't running on the ideas he'd supported in the past. If anything, he was running against the older versions of himself. He apologized for his role in tough-on-crime policies that contributed to mass incarceration. He said his initial vote for the war in Iraq had been a mistake. He seemed to accept, albeit grudgingly, that it might be a good idea to legalize marijuana.

On health care, he promised continuity, building on the Affordable Care Act but not tearing it down. But even there, his plan was to spend three quarters of a trillion dollars to fix a law that wasn't delivering on its promises—a tacit admission that, as Sanders and other single-payer supporters often argued, Obamacare had failed to fully accomplish its goals.

What had happened was clear: The Democratic Party had moved. And so, in turn, had Joe Biden.

After Sanders took the lead in early primaries, Biden's moderate challengers, Buttigieg and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, dropped out so that the party could consolidate around him. He was its standard-bearer.

Biden had won by rejecting Sanders' brand of socialism, but he had also compromised with it. Biden didn't become a revolutionary or develop a hidden love for the authoritarian regimes to which Sanders has sometimes been attracted. But he could compromise because of something he already believed in: the power of government, big government, as a force for good and a tool for solving nearly every imaginable problem.

In his announcement speech, Biden made this abundantly clear. "Well, folks," he said. "I'm going to say something outrageous. I know how to make government work—not because I've talked or tweeted about it, but because I've done it. I've worked across the aisle to reach consensus. To help make government work in the past. I can do that again with your help."

It wasn't just that Biden had spent his whole life in office. It's that for Biden, serving in government had been an act of personal redemption at his moment of greatest personal pain.

In December 1972, just weeks after he won his first Senate race, Biden's wife and 1-year-old daughter were killed in a car accident. In the immediate aftermath, a distraught Biden wasn't sure if he would take office. But under gentle pressure from the late Montana Sen. Mike Mansfield, then the Senate majority leader, he did.

Biden found a place and a purpose in the U.S. Senate. It became his surrogate family, the institution he loved most, carrying him through the vast majority of his adult life. The Senate—and by extension the government it represents—was there for him when he needed it.

This is why he constantly complains of a politics that's mean-spirited, divisive, and polarizing. It's why he constantly champions compromise, working across the aisle, and bipartisanship more than any specific policy outcome. For Biden, that's what politics is, and that's what government can do. He sees endless potential for government to bring people together—and even to bridge his own divides with a fierce rival such as Bernie Sanders.

In advance of the March debate, Biden announced that he would back two new policies. The first was a proposal from Elizabeth Warren that would allow for the elimination of student loan debt through bankruptcy. The second was a plan to make public universities free for lower- and middle-income families. His plan didn't go quite as far as Sanders', but it went out of its way to meet him in the middle. Even as its likely presidential nominee, Biden wasn't leading the party. He was revealing where it already was.

The Viral Future

But that still leaves the question: Where will the Democratic Party go next?

Once again, Sanders provides a clue. Sanders' 2020 campaign had a number of problems. He overrated his own success in 2016 against Hillary Clinton, who elevated his candidacy with a poorly run campaign of her own. Polls found that although Democratic voters were sympathetic to much of his agenda, they were skeptical that a cantankerous self-described socialist could actually beat Trump, their highest priority.

But the fundamental problem for Sanders was demographic. "It's not just that he ran up the numbers with young people," says Kristen Soltis Anderson, a GOP pollster and co-founder of the firm Echelon Insights. "It's also that he got crushed by old folks." Sanders targeted young voters, but although they have an outsize presence in political discourse, especially online, there just weren't enough of them to outweigh the older voters who make up the party's base. "The loudest and most vocal people in the Democratic Party are not the majority," Anderson says.

But young voters—the second party within the Democratic Party—aren't going away. Over time, they are likely to exert more influence. And unlike baby boomers, who became somewhat more conservative as they aged, they show no signs of moderating.

"Young voters have never known a good economy," Anderson says. "They graduated into the Great Recession, moved to cities with high housing costs, and were saddled with unprecedented student loan debt. That makes them up for something different."

Something like socialism. For the last several years, polls have consistently found that young adults have more favorable views of socialism than do their elders; voters under 40—roughly the age of the oldest millennial—also say they're far more willing to vote for socialists. Those voters don't comprise a majority of the Democratic Party now. But without some major, trajectory-altering event, their influence will grow over time.

Which brings us back to COVID-19. Just as it looked like Biden had locked up the nomination, America was struck with a global pandemic—and embarked on an unprecedented economic shutdown in response. As infection numbers and body counts grew around the globe, American states and cities forcibly shuttered major parts of their economies. By the second week in April, more than 16 million people had filed for unemployment insurance, making the downturn worse than the Great Recession. The Senate passed an emergency $2 trillion recovery bill, the largest on record. By April 8, there were roughly 78,000 confirmed cases, and 4,111 deaths, in New York City alone.

In one sense, this played into Biden's hands. Federal health care agencies had failed to manage the development and rollout of mass testing for the virus, leaving policy makers operating in the dark. Biden's argument—that he had the experience necessary to make government work—seemed newly relevant. In his pandemic response plan, Biden emphasized bureaucratic competence, calling for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to build "real-time dashboards" to manage supply chains, to use "sentinel surveillance programs" to manage testing deployment, and to stand up multiple mobile testing centers in every state.

Yet Biden struggled to adapt to the new, mostly online campaign environment: His first attempt at a virtual town hall was plagued by technical glitches, starting three hours late and delivering virtually unintelligible audio. Later attempts to sit for broadcast news interviews were foiled when local networks in major cities cut in to cover press conferences by mayors and governors.

Sanders, who had always thrived online, continued to do so, using the nationwide lockdown as an opportunity to broadcast multiple streaming events that received well over a million views. The cratered economy, meanwhile, meant that the misfortunes of young voters would continue. In April, when he finally suspended his campaign, Sanders boasted in a livestream that he was "winning the ideological battle and winning the support of young people."

Between the two candidates, an observer could glimpse the Democratic Party's past and present as well as its future: Biden, the avatar of the establishment, was focused on bureaucratic competence but struggled to remain relevant, while Sanders, the insurgent, pressed for sweeping policy changes while criticizing the powers that be. Biden had won the battle, but Sanders was winning the war. The revolution would come, just more slowly than expected. And normalcy, whatever that meant, might never return.

Show Comments (80)