No, Cuba Is Not Exactly the Cancer Pioneer Nova Attempts to Present

The myth that this authoritarian island provides better medical treatment just won’t die.

Nova: Cuba's Cancer Hope. PBS. Wednesday, April 1, 9 p.m.

I feel moved to poetry by the latest episode of Nova, the PBS science documentary science series. Perhaps you remember the classic lines about the little girl with the little curl in the middle of her forehead: "When she was good/she was very, very good/But when she was bad, she was horrid."

That's perfect description of Cuba's Cancer Hope, which is partly an absorbing exploration of the use of immunology in the treatment of cancer, and partly an embarrassingly puffy ode to the Castro brothers' totalitarian island. Watching it might trigger your latent schizophrenia; or maybe just induce you to write a pleading letter to TiVo encouraging them to get to work on that long-promised button that allows to automatically skip through communist drivel with a single click. Let me know how it turns out.

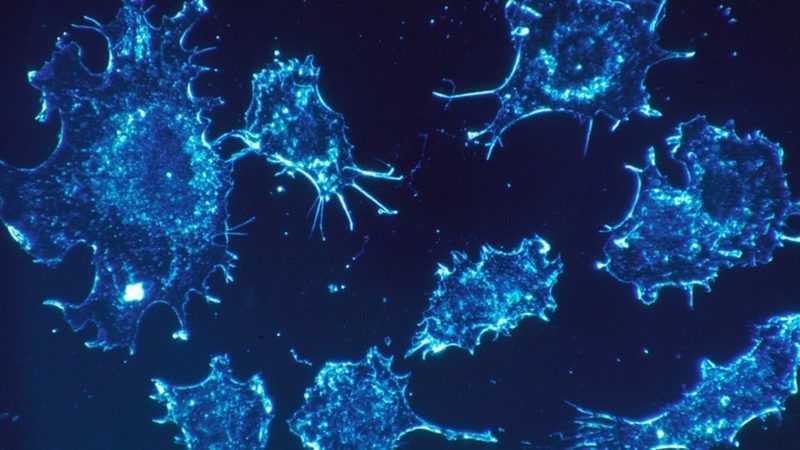

As recently as the 1970s, researchers who tried to figure out why the human body's own immune system didn't attack cancer cells were derided in medical textbooks as believers in witchcraft. (Seriously: Cuba's Cancer Hope shows an example, a useful reminder to those who think that Science [cap S is deliberate] speaks with one immutable and eternal voice are quite daft.) The prevailing belief was that T-cells and other warrior elements of the immune system would never attack tumors because they were part of the body itself.

The witches—er, researchers—kept chipping at the cancer-as-self theory until scientists in the United States and Japan won a Nobel prize in 2018 for showing that two proteins that act as brakes on immune cells were being tricked into action by cancer cells. If those proteins could be reined in, the conventional wisdom now goes, the human body itself could be a potent weapon against cancer. Cuba's Cancer Hope, with sharply illustrative prose and graphics, gives a lucid account of this part of the story.

But when the tale turns to Cuba's development of a lung-cancer vaccine called CIMAvax that enhances the immunological approach with genetic engineering, the show goes off the rails. Cuba, where the national obsession with cigars has triggered a serious lung cancer problem, began experimenting with the drug in the early 1990s. But it wasn't until President Obama restored U.S. diplomatic relations with Cuba in 2015 after a 54-year break, making it easier for Americans to visit the island, that CIMAvax attracted much international interest.

On the Internet, it quickly acquired the mythic status once held by laetrile, another supposed cure for cancer suppressed by The Man. Several hundred Americans traveled to Cuba to take CIMAvax, and Cuba's Cancer Hope is full of testimonials from them—tinged with bitter recriminations against the Trump administration for reviving some of the restrictions on travel to Cuba and forcing them to "break the law" to keep from dying. (Actually, seeking health care in Cuba was never on the list of approved reasons to visit Cuba, and would-be patients can get away with it now the same way they did under Obama: By lying about it to U.S. Customs inspectors, who unless there's an AK-47 in your suitcase, have no way to check what you were doing there.)

Their stories go unchallenged by Cuba's Cancer Hope. In fact, the only question the show has about anything is, "How is it possible for a county as poor and isolated as Cuba to come up with cutting-edge medicines like this?" The answer, of course, is the resplendent humanitarianism of Fidel Castro, who raised Cuba from a pestilent sinkhole into a model of public health that rivals anything in the First World. Though the United States gets a little credit for imposing that nasty embargo that forced Cuba to become heroically self-reliant.

A much more accurate answer would be: Cuba did nothing of the kind. It was anything but isolated—its top immunology researchers learned their trade at the University of Texas. Its supposed advances in public health under Castro are imaginary; it ranked near the top of Latin America in life expectancy, infant mortality and a variety of health statistics before Castro took power, a fact that PBS once knew. (As for current health-care data from Cuba, about the only person who believes any of it is Bernie Sanders.)

And most of all, CIMAvax is far from a "cutting-edge" medicine. The truth is that it barely works at all. As Cuba's Cancer Hope admits in a single throw-away line, "Cuban clinical trials show that it extends life three to five months on average." The five-year survival rate for its users is about 15 percent, roughly the same as that for patients treated with approved U.S. cancer therapies. American oncologists hoot in frustration at patients who want help getting to Cuba to obtain CIMAvax. Says one, quoted in a recent report by Public Radio International: "Without seeing new stats, it's not that impressive… . I am not too worried about people not being able to go to Cuba."

Some American medical authorities think CIMAvax shows promise, and a clinical study of the drug is underway at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo. Perhaps it will someday be proven effective. The same could be said of about 200 other clinical studies of various lung cancer treatments being carried out at the moment, but there's no sign of Nova doing an episode on "Norway's Cancer Hope" or "The Mayo Clinic's Cancer Hope." Of course, none of them would invite any discussion of the genius of Fidel Castro.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Hey, at least it isn't as crazy as the North Korean utopia conspiracy!

Or the one about East Germany having to build a wall to keep out those West German illegal immigrant hordes.

I am making a good salary from home $1200-$2500/week , which is amazing, under a year back I was jobless in a horrible economy. I thank God every day I was blessed with these instructions and now it’s my duty to pay it forward and share it with Everyone, Here is what I do. Follow details…… Read More

But...But, it's Public TV...PUBLIC TV!!! It must be true!!! They know more than us!

Or at least they think they do.

We pay their salaries for which they are forever grateful.

Public TV is not what it used to be. When Ronald Reagan, the American Drug lord became president, he had a purge of public TV and Radio, all the old guard were gone, and the new guys were apparatchicks of the US government. What irked Ronald Reagan and his wall street handlers was that the CIA was used in south America to keep brutal dictators in power and allowing US global corporations to control entire economies. The reports were not lies but fact, substantiated by ex CIA officers. However, I imagine like yourself, these guys don't like their dirty laundry aired out in the open. It is easier to live a fantasy of lies than face the inconvenient realities of truth.

Not sure how far ahead Cuba is in government research, it does train more doctors per capita than any nation in the world. It sends those doctors to poorer countries free of charge. While the AMA in the US makes sure there are not too many doctors so as to assure a shortage and high wages. The school of medicine in Buffalo has not increased its enrollment since the late seventies. Cuba, Venezuela and China have sent doctors to Italy, a NATO member. What has NATO the EU or the US done for Italy? Nothing.

I've been to doctors who were trained in communist countries and those poor countries are getting doctors that are worth every penny their paying.

Ams NPR is unbiased too.

Long ago, PBS/NPR was apolitical. Then, it increasing became an arm of the Democratic Party and Progressives. I have stopped my decades-long financial support.

Socialist countries don't invent things; rather, they steal them. Without capitalists to steal from they'd stagnate.

Communism cannot exist without some support from capitalism. Capitalism can exist quite nicely without any communism at all.

When someone whines about US sanctions, ask them why trade with a capitalist country is required for a worker's paradise to exist.

My mother, now deceased, was a great lady but also a communist. She once explained to me, probably 50 years ago, that Cuba was a shithole only because of the US Embargo. At the tender age of 12 or 13 I pointed out that there were plenty of countries Cuba could trade with and they had plenty of natural resources. I don't remember getting a satisfactory answer to my childish query. I agree with her that the embargo is stupid but Cuba is a shithole because of it's corrupt communist government. End of story.

Enjoy your koolaid, you ignorant mook.

Isn't Cuba where you go to get cancer?

No, you go to your house to get cancer. Of the brain.

Some poor lefty show up to prove how stupid lefties are? You're doing a good job.

I was somewhat miffed when I read this article until I noticed the broadcast date - April 1 - April Fool's Date. Clever, these PBS folks. What a great sense of humor. So subtle, I hardly noticed.

Cuba's healthcare system is so good that thousands of Floridians have risked their lives on makeshift rafts to get there.

Oh, wait...

I used to think Cuba was diploma-milling doctors to send to Angola to kill fascist whitey. But it turns out they had thrice the normal proportion of doctors before Ku-Klux Dems and Republican prohibitionists drove them into the arms of the communists. Whenever God's Own Prohibitionists get a chance to wreck the economy via asset forfeiture, communist/looter parties suddenly gain strength in that jurisdiction. To get rid of communism the best bet is to ditch its vector: the G.O.P.

Hahahahaha, imagine being so stupid you think asset forfeiture abuses are only perpetrated by Republicans.

Bravo Hank. I wish you and your family a speedy escape from this nasty virus.

"...To get rid of communism the best bet is to ditch its vector: the G.O.P."

You've got the tin-foil hat on backwards, Hank.

If you watch any recent Nova shows you will learn most science was invented and practiced by non-whitemen.

It is known.

This single vaccine version is hardly "the cutting edge of cancer treatment". There are loads of immunotherapy models with even more promise. Plus you have viral vectors that are showing immense promise and miracle cures.

It is great that Cuba is participating in the international medical research effort... but you can't seriously pretend that they are the leading edge of research. That's just silly. The entire nation probably doesn't add up to Alabama on the world stage. (Actually not fair... UAB is world class in medical research, and you have Bama and Huntsville and Auburn...)

NOVA has become so full of shit, they should change their logo colors. Unfortunately the same is true with almost all "documentary" programming on PBS. Most NOVA and Nature shows are now breathless doom and gloom reports, that find ways to blame humanity for everything (and include climate change in every context). Too bad, since I recall when these types of nature shows actually focused on the science and offered a sense of wonder and encouragement, and even technical learning.

Even This Old House, which was truly just about rebuilding homes and nerdy dives into various tools and trades, has fallen to the activists, with the most recent season not much more than a pity party about the Paradise, California fire. Hey PBS ass hats--there are other shows that already cover the social and political issues. Put the non-activist nerds back in producer roles.

I haven't watched PBS for a while but I gave up on NPR after the 2016 election. They went completely off the rails with TDS. I was actually embarrassed for them and thought cooler heads would prevail. Didn't happen.

I stopped listening a few years ago when they did a story on how everyone born between certain years should get of the hepatitis tests even if there were no risk factors because you never know. Following that story was a non-ad for a drug company. Once I got in front of the computer, I looked it up and, yup, the company made the test that they were encouraging everyone to get whether they needed it or not.

Is NOVA still Koch funded?

★Makes $140 to $180 reliably online work and I got $16894 in one month electronic acting from home.I am a bit by bit understudy and work basically one to a few hours in my extra time.Everybody will finish that commitment and monline akes additional money by just open this link..... Read More

★Makes $140 to $180 reliably online work and I got $16894 in one month electronic acting from home.I am a bit by bit understudy and work basically one to a few hours in my extra time.Everybody will finish that commitment and monline akes additional money by just open this link…..

More Read

★Makes $140 to $180 reliably online work and I got $16894 in one month electronic acting from home.I am a bit by bit understudy and work basically one to a few hours in my extra time.Everybody will finish that commitment and monline akes additional money by just open this link….. Read More

The myth that the US has an enemy in Cuba just won't die.

Does anyone here understand that the US treats Cuban people like pawns simply because Richard Nixon was a secret partner with Batista? That when he left the Whitehouse he had $35 million in a Swiss Bank account given to him by Batista? (About $3 billion now.)

Read this book, and help us stop starving my people. Please!!

The Mafia's President: Nixon and the Mob

"...Does anyone here understand that the US treats Cuban people like pawns simply because Richard Nixon was a secret partner with Batista?.."

Are you stupid enough to think any other than a fucking lefty ignoramus would believe that stinking pile of shit?

The embargo is stupid, but the Cuban people have only the Castros to thank for their pathetic condition.

Fuck off and die, slaver.

Do you use a pay pal ? in the event if you do you can include an additional 650 weekly in your revenue just working on the internet for three hours per day. check… Read More

Make $6,000-$8,000 A Month Online With No Prior Experience Or Skills Required. Be Your Own Boss And for more info visit any tab this site Thanks a lot just open this link..... Read More

[ Work At Home For USA ] I started earning $350/hour in my free time by completing tasks with my laptop that i got from this company I stumbled upon online…Check it out, and start earning yourself . for more info visit any tab this site Thanks a lot Here... Read More

Cubans always help! Great nation! They visiting our web platform sex in dortmund for sexy chat

Too bad that your slick put down of PBS long delayed coverage of the objectively good work by Cuban scientists had to be tainted by stereotypes. Libertarians should believe in free trade & free travel, not I think in 60 years of a formal (but generally NOT covered) official U.S. policy to "bring about hunger, desperation, and overthrow of government" in Cuba.) Direct quote, Lester Mallory, April 1960. The CBC has covered this story years ago, it once got a brief visit from the PBS news hour, but otherwise ignored by our media. See this CBC story of the Republican businessman from West Bend WI, who voted for Trump but still thinks his life is "worth it" to get the medical treatment that Cuba offers, but US people still cannot get. https://wicuba.wordpress.com/2016/06/27/this-is-pretty-incredible-how-cuba-and-canada-give-u-s-lung-cancer-patient-new-hope/ This is despite the author's implication that the people with advanced lung cancer who like Mr. Phillips have had years of quality life added by being willing -- or forced -- to break the U.S. travel ban (which you accurately state does not allow such life-saving travel), may be either naive or using this as means to attack Trump. Why don't you join in asking for the end of such strangling restrictions on trade, travel & commerce, so that people can benefit on both sides?

Dr Suleiman herbal medicine is the best remedy for Herpes , cancel and HIV, I was a carrier of Herpes and I saw a testimony on how Dr Suleiman cure Herpes, I decided to have a contact with him and asked him for solutions and he prepare the herbal cure for me which i use to cure myself. Thank God, now everything is fine, I'm cured from Herpes by Dr Suleiman herbal medicine, I'm very thankful to Dr Suleiman and i will not stop publishing his name on the internet because of the good work he did for me, You can reach him on his email: suleimanjamiu05@gmail.com

DOCTOR SULEIMAN CAN AS WELL CURE THE FOLLOWING DISEASE:-

1. HERPES 2. HIV 3. HSV1&2 4. HPV

5. Hepatitis A,B,C 6. Diabetes 7. CHRONIC DISEASE