She Said He Said He Saw Demons. Then He Had to Give Up His Guns.

A bizarre Florida “red flag” case shows the importance of safeguards that protect people’s Second Amendment rights.

The allegations against Kevin Morgan were alarming. They described just the sort of circumstances that Florida legislators had in mind when they approved that state's "red flag" law in 2018, three weeks after the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland.

Morgan's estranged wife, Joanie, claimed he was depressed, suicidal, and obsessed with the apocalypse, which he thought was imminent. She said he was stockpiling food, gold, guns, and ammunition in anticipation of the end times; that he talked about seeing, hearing, and wrestling with demons; and that he had performed a ritual that involved rubbing "oils" on their children and the walls of their house. She reported that he was abusing the drugs he had been prescribed for chronic pain, had talked about dismembering his former wife, had intimated he would do the same to her if she ever disrespected him, and had threatened to kill her with succinylcholine, a paralytic agent used during surgery and intubation.

On the strength of such claims, Joanie Morgan obtained a temporary domestic violence protection injunction, an involuntary psychiatric evaluation order under the Florida Mental Health Act (a.k.a. the Baker Act), and a temporary "risk protection order" under the red flag law, which authorizes the suspension of a person's Second Amendment rights when he is deemed a threat to himself or others. All three were ex parte orders, meaning they were issued without giving Kevin Morgan a chance to rebut the allegations against him.

But when it was time for a judge to decide whether the initial gun confiscation order, which was limited to 14 days, should be extended for a year, Morgan got a hearing, and the lurid picture painted by his wife disintegrated. By the end of the hearing, in an extraordinary turn of events unlike anything you are likely to see in a courtroom drama, the lawyer representing the Citrus County Sheriff's Office, which was seeking the final order, conceded that he had not met the law's evidentiary standard, and the judge agreed.

This bizarre case vividly illustrates why legal representation and meaningful judicial review are necessary to protect gun owners from unsubstantiated complaints under red flag laws, which 17 states and the District of Columbia have enacted. But it also shows that police and prosecutors, who in Florida are the only parties authorized to file red flag petitions, are not necessarily diligent about investigating allegations by people who may have an ax to grind. That problem is especially serious in the states that allow petitions by broad categories of individuals whose accounts may be colored by personal animus, including current or former spouses, lovers, and housemates as well as in-laws and close or distant blood relatives. Without adequate safeguards, respondents can lose their constitutional rights based on little more than an aggrieved individual's unverified assertions.

'It Wasn't Him That Had Gone to the House'

Circuit Judge Peter Brigham issued the ex parte risk protection order against Morgan on September 18, 2018, six months after Florida's red flag law took effect, in response to a petition by Rachel Montgomery, a detective with the Citrus County Sheriff's Office. It was the first time the sheriff's office had used the law.

In the affidavit supporting her petition, Montgomery said she responded to a complaint from Joanie Morgan alleging that her husband had violated the temporary domestic violence protection injunction by returning to the house in Citrus Springs they used to share and retrieving clothing, medications, "several firearms," and his Ford Mustang. Montgomery paraphrased the claims Joanie Morgan had made in her petitions for the injunction and the Baker Act examination: that "the respondent has had a decline in mental stability over the last four months" and "has displayed irratic [sic] behaviors to include making threats to dismember a former paramour and threats to kill his entire family while yielding [sic] a vial containing a paralytic agent." She added that "the respondent has purchased several firearms and ammunition during this time period."

At this point, Montgomery later testified, she had done no investigation beyond talking to Joanie Morgan and reading her petitions. Montgomery said she subsequently discovered there was no basis for the claim that Kevin Morgan had violated the injunction by visiting the house. "I determined that it wasn't him that had gone to the house," she said. "It was actually a pool maintenance worker that had been by the house." Furthermore, "the firearms had been transferred prior to his risk protection order" in response to the domestic violence injunction, meaning there were no guns for Morgan to retrieve from the house.

Montgomery did read the Baker Act petition that led to Morgan's court-ordered psychiatric evaluation, but she did not mention the outcome of that evaluation. On September 13, 2018, police handcuffed Morgan and took him to The Centers, a mental health facility in Ocala, where he spent the night. The next day, a psychiatrist determined that he did not meet the law's criteria for involuntary treatment. A discharge form dated September 14, 2018, described Morgan as "alert and oriented" and "calm and cooperative." It explained that "Kevin was evaluated by the psychiatrist and it was determined that Kevin does not present as a danger to himself or others."

Yet here was Montgomery, four days later, asserting that there was "reasonable cause to believe" Morgan "poses a significant danger of causing personal injury" to himself or others "in the near future." Judge Brigham agreed, and there was no reason to think he wouldn't. Statewide data indicate that Florida judges always grant petitions for ex parte risk protection orders.

A follow-up mental health report from The Centers, written two days after Brigham approved the temporary risk protection order, described Morgan's appearance as "appropriate," his behavior as "compliant," his mood as "stable," his thought process as "organized," and his judgment and impulse control as "good." Based on prescription records and a drug screen, Stefanie Glover, a licensed mental health counselor at The Centers, reported that Morgan was "displaying no drug abuse." She also said Morgan "did not display any signs or symptoms of paranoia, psychosis or delusions." In the "trauma" section of the form, Glover typed: "Client is being mentally and emotionally abused by his wife. Client stated that he filed for a divorce on Monday September 17th, 2018."

Glover's conclusions about Morgan jibed with an August 29, 2018, letter from his personal physician, Ulhaus Deven. "He has shown no sign of abusing the opioids prescribed to him," Deven wrote. "He has not had any indication of depression or suicidal ideation."

'This Puts Us in an Awkward Situation'

On September 28, 2018, 10 days after Brigham issued the temporary risk protection order, he held a hearing to determine whether there was "clear and convincing evidence" that Morgan posed "a significant danger" to himself or others. That is Florida's standard for issuing a final risk protection order, which lasts up to a year and can be renewed for another year.

At the hearing, the sheriff's office was represented by its lawyer, Robert Batsel, while Morgan was represented by Crystal River attorney J. Michael Blackstone. I listened to the official audio recording of the hearing, which lasted about two hours and 20 minutes. It included testimony by Kevin Morgan, Joanie Morgan, and her mother as well as Detective Montgomery.

In addition to refuting the claim that Kevin Morgan had violated the domestic violence injunction, Montgomery described him as "very calm" when he was taken into custody for the Baker Act examination. Responding to questions from Blackstone, she said Morgan was polite and cooperative, neither raising his voice nor behaving erratically, and seemed to be in control of his faculties.

Joanie Morgan's testimony was tearful, highly emotional, scattered, and frequently vague. She reiterated her earlier allegations and added a few more. But when Blackstone asked whether she had any evidence to corroborate what she claimed her husband had said and done, she admitted that she did not.

There were no witnesses to confirm his alleged threats and no photographs of oil on the walls, of the hypodermic needles he allegedly had stashed away to inject the succinylcholine, or of the food, gold, weapons, and ammunition he allegedly had accumulated in preparation for the end times. Nor had police ever visited the house to confirm any of those details. Blackstone also noted that, despite Joanie Morgan's portrait of her husband as dangerously deranged, she was planning to build a new house with him on property they had purchased together in April 2018, and she had left her children overnight with him that August, in the midst of his supposed breakdown, to attend a conference in Tampa.

Joanie Morgan's mother, Susan Harper-Clements, tried to back up her daughter's portrayal of Kevin Morgan as dangerous, but the evidence she offered fell notably short. For example, she mentioned "conversations" after the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas. "Kevin had told me that the NRA…was all into this gun thing and that you couldn't even buy the bullets you wanted, because people were stockpiling," she said. "And he said, 'When they're all through with this, you won't be able to buy guns and ammunition.'" On cross-examination, Blackstone noted that such comments hardly proved homicidal intent. "He has never threatened anyone in your presence, has he?" he asked. "No," Harper-Clements replied.

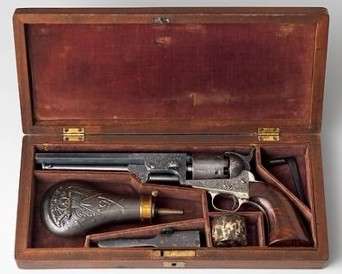

Kevin Morgan's demeanor at the hearing was as Montgomery and the staff at The Centers had described it: calm, polite, and cooperative. He denied seeing demons, making threats, or obsessing about the apocalypse. He denied that he had recently been stockpiling guns, saying he had acquired his collection of roughly 40 rifles and handguns over the course of more than two decades. The only guns he had acquired recently, he said, were three black-powder pistols he had bought the previous spring and summer—antique replicas ill-suited for the end times.

What about the mostly empty vial of succinylcholine that his wife had presented to sheriff's deputies as evidence of Morgan's deadly designs? Morgan recalled that his wife, a nurse who had worked at two local hospitals, had once accidentally brought home just such a vial, saying she had put it in her lab coat pocket after participating in the treatment of a patient who had suffered a cardiac arrest. Morgan, who also has a nursing degree, had managed the emergency room at one of those hospitals, but he left that job in January 2015 because of a disability caused by spinal stenosis. After that, he no longer had access to drugs such as succinylcholine. Given the expiration date on the vial that his wife gave to police, Morgan said, it was clear he could not have been the person who had obtained it.

After the last witness testified, Blackstone asked Brigham to deny the petition by the sheriff's office. "The testimony, frankly, does not make any sense," he said. "There's no objective evidence for the court to base a ruling on. There's been ample opportunity. The police could have gone and looked at the inside of the house and verified that there were gold coins or gold bullion or oil on the walls or anything else. We basically only have the word of a woman that's in the early parts of a divorce. Most of the testimony has already been contradicted by Mr. Morgan. It's unpersuasive under any circumstances, and the standard is 'clear and convincing.' With all due respect to Mr. Batsel, who I think a lot of, I don't think he's carried that burden. At best, it's a swearing match."

At this point, Batsel got up and admitted that Blackstone was right. "I've conferred with my client," he said, and "they won't object to me tending to agree. This puts us in an awkward situation. The sheriff's office is coming into this with all the best intentions…The legislature has put us in a bit of a box, and that's OK; we're going to figure it out. But in a 'he said, she said,' where the evidence, I frankly will agree, does not meet 'clear and convincing,' we don't want to waste the court's time."

Blackstone thanked Batsel for his candor. "I can't tell Mr. Batsel how much I appreciate, in the world today, somebody standing up and just accepting what the facts are," he said. He also thanked the sheriff's office. "I think we're all learning as we go," he said. "It's a new statute. It's going to put huge burdens on everybody."

Brigham ratified the agreement between both sides that the sheriff's office had failed to make its case. "I don't think I've heard clear and convincing evidence," he said. "I found Mr. Morgan's testimony to be credible." Explaining his decision in an order he issued later that day, he said, "The issue came down to a credibility determination between the respondent and his current wife. The court found the respondent credible and that the petition was not proved by clear and convincing evidence. [Regarding] the only piece of physical evidence, a vial of drugs, [it] was never clearly, or convincingly, explained from whence it came."

'You Have to Go in and Prove That You're Not Guilty'

Blackstone, who supports red flag laws in principle, thinks Florida's statute worked as intended in this case. "I thought you had a well-intentioned police officer who sat on the stand and told the truth," he says. "I thought you had an exceptionally well-intentioned and competent attorney for the Citrus County Sheriff's Office who did a fabulous job. I thought I did a competent job in representing Kevin, and I thought that the law worked the way it was supposed to."

At the same time, Blackstone recognizes that it's important to have a lawyer in situations like this. "It's always dangerous to go into court without a lawyer," he notes. Without "competent counsel," he says, this case "might have turned out the same way," but "it might have turned out entirely different."

Florida, like nearly all of the states with red flag laws, does not provide court-appointed counsel for respondents. Colorado is the only state that guarantees a right to counsel for respondents who can't afford a lawyer or choose not to hire one.

Blackstone estimates that a single red flag case ordinarily would cost $2,500 to $5,000 in legal fees. Morgan says Blackstone, who also is handling his divorce, charged him about $1,500. That was on top of the attorney fees and extra living expenses he incurred as a result of his other legal battles with his wife. "I had about $13,000 or $14,000 in savings, and by the time all this was done, I had nothing," he says. "I was lucky to have a lawyer. I was lucky to be able to afford it."

Morgan's take on Florida's red flag law is less sanguine than Blackstone's. The law ostensibly puts the burden of proof on the agency seeking an order. But in practice, Morgan says, "you have to go in and prove that you're not guilty."

The automatic issuance of ex parte orders means that when a respondent gets his day in court, the playing field is slanted sharply against him. The judge is deciding whether to maintain the presumptively protective status quo or change course and give the respondent legal access to guns he might use to kill himself or someone else. That prospect tends to loom larger than the possibility that a respondent who does not really pose a threat will unfairly but temporarily lose his Second Amendment rights. Those dynamics help explain why judges in Florida issue final orders about 95 percent of the time.

Morgan's case nevertheless shows that the standard of proof matters. In the end, both parties and the judge agreed that the sheriff's office had not presented clear and convincing evidence. While that is the standard in most states with red flag laws, four states and the District of Columbia require only proof by "a preponderance of the evidence," meaning any probability greater than 50 percent. When laws combine a low standard of proof with undefined terms such as "a significant risk," "a significant danger," or "a risk of danger," the respondent does not have much chance of prevailing.

Another safeguard is requiring that petitions be filed by police or prosecutors, as Florida does. While anyone who knows a potentially dangerous person can still share his concerns with the authorities, police are supposed to act on those concerns only when they consider them well-grounded. The idea is to have dispassionate officials evaluate complaints from people who may have personal biases. But that goal is defeated if police simply record and pass along allegations by aggrieved parties.

Even allowing for Citrus County's inexperience with the red flag law at the time it sought the orders against Morgan, one has to ask why a law enforcement agency would go to court with a case so weak that its own attorney ended up throwing in the towel at the end of the hearing. Police should not seek ex parte orders without evidence of an imminent threat, and they should not seek final orders unless they are confident they can meet the law's requirements. Such caution is especially important when judges can be expected to rubber-stamp ex parte orders and approve nearly all of the final orders police request.

The possible cost of deciding not to seek or issue an order—a preventable suicide or homicide—has to be weighed against the certain cost of suspending someone's constitutional rights. Police should conduct a thorough investigation before trying to do that. In this case, easily discoverable facts—including the existence of Morgan's supposed hypodermic needles and end times stockpile, the whereabouts of his guns prior to the temporary risk protection order, and the provenance of the succinylcholine—were either not clarified until the hearing or remained unresolved even then.

The sheriff's office "jumped into a civil action without completing a proper investigation," Morgan says. "I don't think the average person understands just how dangerous these laws are. Hopefully, if my story can get out, folks will see how easily [red flag laws] can be used against someone for revenge or to get an upper hand in [a custody dispute]. I want people to know how these laws can be used improperly, in the hope that some reforms will take place. We need protection for falsely accused individuals and stiff punishment for those who abuse the system."

Show Comments (150)