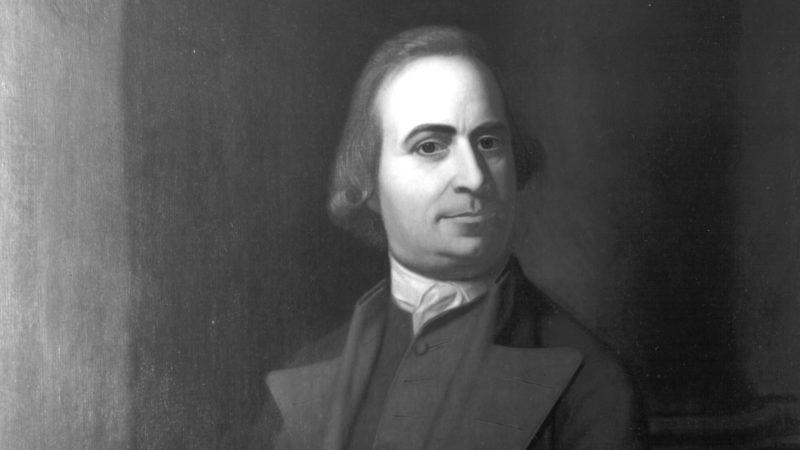

What Would Samuel Adams Think of Michael Bloomberg's Campaign?

"I hope our country will never see the time, when either riches or the want of them will be the leading considerations in the choice of public officers," Adams wrote in 1776.

This Presidents Day, I am thinking of John Hancock.

Hancock was president of the Continental Congress, the body that named George Washington general of the Continental Army. Hancock was the Michael Bloomberg of his day—a politician simultaneously appreciated for his great wealth and resented for it.

I tell this story in my biography of Samuel Adams. John Hancock had inherited a fortune of what today would be about $15 million from his uncle, the merchant Thomas Hancock. John Hancock may have used some of this money to help Adams, who was poorer, pay off debts Adams owed.

While Adams and Hancock were allies against King George III, they were also rivals in Massachusetts politics. John Adams once reported that Samuel Adams "had become very bitter against Mr. Hancock, and spoke of him with great asperity in private circles."

In Philadelphia in late 1775, Samuel Adams was annoyed to learn that Hancock had planned a ball, which seemed extravagant and inappropriate under the wartime circumstances. In January 1776, Samuel Adams wrote to his fellow patriot Elbridge Gerry, "I hope our country will never see the time, when either riches or the want of them will be the leading considerations in the choice of public officers." The letter went on to contend that "giving such a preference to riches is both dishonourable and dangerous to government," indicating "a base, degenerate, servile temper of mind."

When John Hancock was elected governor of Massachusetts in 1780, Adams pronounced himself "chagrined" and "disappointed" at the result. Yet the two men eventually reconciled, and Samuel Adams wound up serving as lieutenant governor under Hancock.

When the wealth of presidential candidates emerged as a campaign issue during the previous election cycle, I wrote a column concluding, "Wealth can buy admiration but it can also bring isolation. Samuel Adams had a point when he cautioned against it becoming a big factor in voter decisions. We'd be better off spending less time thinking about how much money the candidates do or don't have and more time considering how likely their policies are to help enrich or impoverish the rest of us."

What was true of Trump then is true of Bloomberg now. One hears Blooomberg's wealth cited as a reason to oppose him. "Michael Bloomberg came in on the billionaire plan—just buy yourself the nomination," Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, another contender for the Democratic nomination, said recently. Senator Bernie Sanders has made similar statements: "We have an individual worth some $60 billion, who is in an unprecedented way, trying to buy the election….We are going to defeat a billionaire."

One also hears Bloomberg's wealth mentioned as a reason to vote for him—it can buy, the argument goes, lots of well-crafted campaign commercials against Donald Trump. That is more anti-Trump commercials than the non-billionaire candidates will be able to afford. Perhaps this higher volume of commercials will increase the chances of defeating Trump, a goal that is dear to Democratic primary voters.

Hancock's money helped to buy him the presidency of the Continental Congress and the governorship of Massachusetts, but it never made him president of the United States. He died in 1793, his fortune largely diminished by war, inattention, and mismanagement.

Other candidates who followed had greater success in purchasing the office. John F. Kennedy joked at the 1958 Gridiron dinner that he had received a telegram from his wealthy father: "Jack—Don't spend one dime more than is necessary. I'll be damned if I am going to pay for a landslide." (This is sometimes rendered as "don't buy a single vote more than necessary.") That joke was less funny if you were Hubert Humphrey or Richard Nixon.

In America, journalists and professors may envy or even hate the rich. Most of the rest of the population, though, has traditionally devoted less energy to hating millionaires and more energy to trying to get rich themselves, or at least to emulate their lifestyles.

Bloomberg's candidacy will be a test, in part, of whether this remains true even of the Democratic primary electorate. Will the voters be bitter toward the billionaire the way that Samuel Adams sometimes was toward Hancock? Or will they appreciate Bloomberg's willingness, like Hancock's, to spend his fortune to advance their cause? And if, like Samuel Adams, today's voters sometimes feel both these emotions at once, how will that translate in the voting booth?

Show Comments (44)