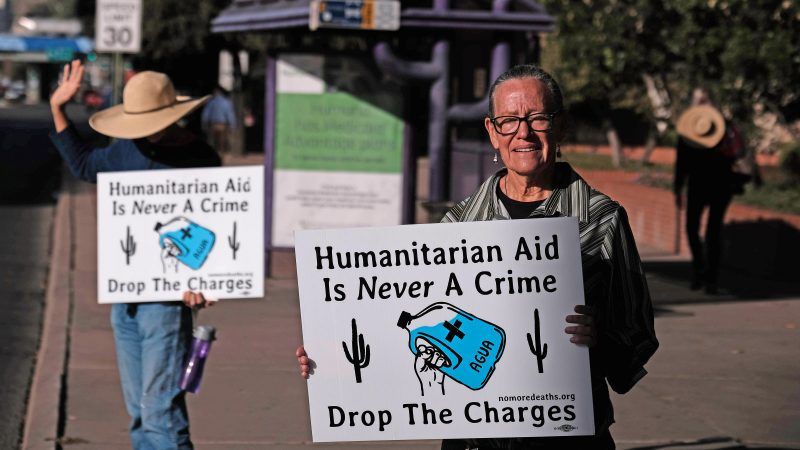

Jury Confirms That Providing Humanitarian Aid to Migrants Is Not a Crime

Scott Warren of No More Deaths was acquitted on two charges of harboring illegal immigrants.

A jury last week acquitted a humanitarian aid worker of harboring undocumented immigrants, ending a courtroom saga that sparked debate over the legal intricacies of being a good Samaritan.

"The verdict is a clear sign that the work that we do should be and is in fact legal," Jeff Reinhardt, a spokesperson for No More Deaths, tells Reason. "It affirms our right to give aid to people who need it, and for those people in need of aid to receive it, knowing that it is not a criminal act."

Scott Warren, a volunteer with the group No Más Muertes/No More Deaths, maintained that he broke no laws when he helped Kristian Perez-Villanueva and Jose Arnaldo Sacaria-Goday, two migrants from Central America who were suffering from dehydration after their long trek across the U.S.-Mexico border. Warren gave the two men food and water, and allowed them to spend three nights at "the Barn"—a communal meeting place used by various aid groups in Ajo, Arizona. Reinhardt notes that, in such circumstances, there is no legal obligation to call Border Patrol.

The case hinged on intent: Did Warren set out to violate the law, or was he merely trying to alleviate the men's suffering? Prosecutors argued the former, but the jury settled on the latter.

Warren would have faced 10 years in prison if convicted. He was previously tried in June, but that jury deadlocked.

Groups like No More Deaths seek to end the steady stream of lives lost across the U.S.-Mexico border, where treacherous terrain and extreme temperatures make the trip across the desert a potentially fatal one. "Since the year 2000, there's been over 3,000 [human] remains recovered," says Reinhardt, but that only "represents a small percentage of the actual number of people who have perished." Those making the trek are subject to intense heat and sunlight, leading to cases of hyperthermia when the body temperature skyrockets above normal levels. Nighttime sees plunging lows, especially during the winter, where people in sweaty clothing are particularly vulnerable to hypothermia.

Efforts to criminalize acts of human kindness have become more commonplace in recent years, blurring the line between illegally crossing the border and helping someone who is suffering severely. In February, a Texas city attorney was arrested and detained for stopping on the side of the road to talk to three young migrants who flagged her down as she drove by, one of whom was gravely ill. Days later, on March 1, four volunteers from No More Deaths were sentenced to 15 months probation and a fine after they left food and water in the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge.

It's a high price to pay for attempting to extend care to people who may be dying of starvation and dehydration. But the absurdity of their sentence is even more apparent when considering the punishment given last week to Michael Bowen, a Border Patrol agent who mowed a migrant down with his truck in 2017. He received three years of probation.

Unfortunately, this isn't the first time Border Patrol has employed violent tactics to track down a fleeing migrant. As I wrote in March, the group's "chase and scatter" techniques are well-documented: Migrants have been beaten with guns, chased and bitten by dogs, and pursued by low-flying helicopters. These strategies often serve to separate groups and disorient them, increasing the chance that they will get lost and die in the desert.

But when it comes to future prosecutions for humanitarian aid workers, Michael Bailey, the U.S. attorney for Arizona, showed no signs of softening.

"Although we're disappointed in the verdict, it won't deter use from continuing to prosecute all the entry and reentry cases that we have, as well as all the harboring and smuggling cases and trafficking that we have," he said in a statement. "We won't distinguish between whether someone is harboring or trafficking for money or whether they're doing it out of a misguided sense of social justice or belief in open borders." But one need not believe in open borders to believe that basic human kindness shouldn't be a crime.

Show Comments (176)