The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

How to Attend Oral Arguments at the Supreme Court

An in-depth look at the written and unwritten rules to attend oral argument at the Supreme Court

Last week, I attended oral argument at the Supreme Court in DHS v. Regents of the University of California (the DACA case). The experience was extremely problematic for reasons I will explain in a subsequent post. (I offered a preview on my Twitter feed.) This post will explain how to attend oral arguments the Supreme Court. The process is complicated for those not familiar with the written and unwritten rules.

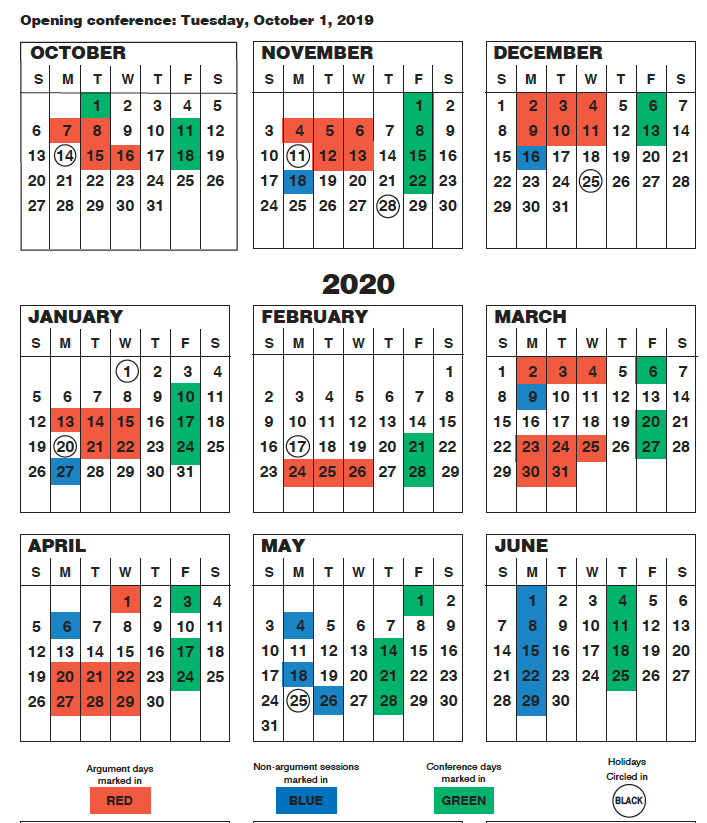

Argument Days on the Court's Calendar

Configuration of the Supreme Court

The Court chamber is divided into several sections. (On the ground floor of the Supreme Court is a to-scale diorama that, more or less, accurately represents the current configuration of the Court.)

The Justices sit on the angled bench. The Clerk sits to the left of the bench. The Marshal sits to the right of the bench. Counsel for the parties sit at the first row of tables, right in front of the bench. Generally, each side brings three or four attorneys. The arguing attorney stands in front of the lectern. (Do not try to adjust it during argument!) The second row of tables in front of the bench is reserved for other attorneys.

The press sit on the left side of the Court, in the red seats in front of the columns. Members with "hard passes" have reserved seats. Other members of the media can request access on a case-by-case basis. Reporters without reserved seats will sit behind the columns on the left side of the Court. The red seats on the right side of the Court are reserved for guests of the Justices. There are plaques installed on the seats with each Justice's name. The law clerks sit on the far right side of the Court, behind the columns.

Members of the Supreme Court bar sit in front of the brass bar in the middle of the Court. The diorama depicts ten rows of ten seats. I only observed eight rows of ten seats. There are also six chairs on the left side of the Court. I'll call it 86 seats in the bar section. (I welcome corrections if others have precise numbers).

The general public sits behind the bar. There are 15 benches, each seats 7 people. Generally, one chair is added in the aisle next to each bench. I'll call it 120 seats. (Again, I welcome corrections for precise numbers.)

The Court also allows people to sit in the back of the chamber for three minutes to watch parts of the oral argument. After the three minutes are up, other people will cycle through.

Obtaining a publicly-available seat

Before I was admitted to the Supreme Court Bar, I waited on the public line a handful of times. Perhaps my longest wait came in 2010 for McDonald v. Chicago. I arrived the night before around 9:00 p.m. When I got on the line, I was #40 or so. The following morning, however, I was #48 or so. About eight people cut in front of me by the dawn's early light. In some cases, paid line waiters would save several spaces. In other cases, people snuck in when no one was looking. The Supreme Court police refuse to monitor the line, and will not intervene if people cut. (More on cutting later.)

After clearing security, those with golden tickets can wait in the cafeteria or check out the Supreme Court's exhibits. Or (in my case) go to a friend's house nearby and grab a shower. So long as they are back to the Court around 8:30, they will be allowed to enter.

Obtaining a reserved seat

There are several ways to obtain a reserved seat.

First, each Justice has a designated number of tickets they can give away. This process is as opaque as it sounds. As they say, you have to know someone.

Second, counsel of the parties receive a certain number of seats for guests. This number will vary depending on how many empty seats there are. Guests who are members of the Supreme Court bar can sit in the bar section. Non-attorney guests can sit in the public section. In consolidated cases with several parties, counsel will have fewer tickets.

Third, parties participating in bar admissions will also receive reserved seating. Attorneys who are members of the highest court of their state for three years can apply for admission to the Supreme Court bar. Applicants have to contact the clerk well in advance. Generally, at the start of each session, the Court will hear several motions for admission. One attorney will rise, and state the names of the members he or she is seeking to admit. After all the names are called, the Chief Justice will ask the inductees to rise, and take the oath. The entire process takes a few minutes, depending on how many people are seeking admission.

On argument days, the Court hears several "small group admissions" (up to 12 applicants). Often, a few small groups are allowed to move for admission on a single day. For example, during the DACA arguments, three attorneys moved for the admission of about 25 members. On non-argument days, the Court hears "large group admissions" (up to 50 applicants). Each person seeking admission is allowed to bring one guest, who sits in the public section.

Many of the bar admissions are scheduled months in advance, to permit the inductees sufficient time to make travel arrangements. But there is another, lesser-known way to attend argument in a specific case. Attorneys can ask the Clerk to schedule a bar admission when a specific case is being argued. The moving attorney, and the attorney taking the oath, are both guaranteed seating in the bar section. I am familiar with this approach, because I employed it in 2016 to attend oral arguments in Zubik v. Burwell. (Ilya Shapiro moved for my admission; the Chief, perhaps against better judgment, granted the motion.)

Obtain a seat in the bar section

Members of the Supreme Court bar, who are not counsel in a given case, and do not have a reserved seat, can also wait on the bar line. This line generally forms on the left side of First Street, and snakes towards Maryland Ave NE. In 2015, the Court prohibited paid line waiters on the bar line. (Lawyers are still saving spots on line; more on that problem later.)

The bar line operates very differently than the public line. First, on the public line, there are 50 guaranteed seats. On the bar line, the number of reserved seats depends on how many seats are reserved for bar admission and for co-counsel. Second, on the public line, Court personnel hand out numbered tickets, so people can easily lay claim to their spot. On the bar line, no tickets are issued. Rather, members of the bar line are asked to enter the Court, go through security, and form another line on the ground floor. At that point, personnel check IDs (to make sure the lawyer is admitted to the bar), and then hands them a numbered ticket. (The process of entering the Court and clearing security creates many, many opportunities for the ordering of the line to change.)

Third, if members of the general public do not secure a seat, they are out of luck. But members of the bar are only partially out of luck. They can sit in the lawyers lounge, and listen to a live-feed of the audio. By my (rough) count, there are about 100 seats in the lawyers lounge. For the DACA case, every seat was full. I heard that during the same-sex marriage cases, there was standing room only. As a result, members of the bar will generally be able to listen, but not see a case being argued.

Summary

Unless you know someone, the only guaranteed way to attend an oral argument is to be one of the first 50 people on the line. And to be really sure, you should stand as close as possible to the front to account for line cutters. If you are a member of the bar, your position is far more uncertain, because the number of available seats depends on how many attorneys are seeking admission in a given day. But, if you are able to obtain a reserved seat, you do not have to worry about these variables.

The next post in this series will explain my experiences during the line for the DACA case. The third post in this series will offer some suggestions to improve the process.

Show Comments (25)