The Economy Keeps Growing, but Americans Are Using Less Steel, Paper, Fertilizer, and Energy

Good news! We’re getting more while using less.

Environmental scientist Jesse Ausubel remembers the moment his research trajectory changed. Over dinner one night in 1987, his friend and colleague Robert Herman, a physicist with a wide range of interests, wondered aloud, "Are buildings getting lighter?" That apparently simple question inspired the pair to begin looking into the "material intensity" of the modern world.

In 2015, Ausubel published an essay titled "The Return of Nature: How Technology Liberates the Environment." He had found substantial evidence not only that Americans were consuming fewer resources per capita but also that they were consuming less in total of some of the most important building blocks of an economy: things such as steel, copper, fertilizer, timber, and paper. Total annual U.S. consumption of all of these had been increasing rapidly prior to 1970. But since then, consumption had reached a peak and then declined.

This was unexpected, to put it mildly. "The reversal in use of some of the materials so surprised me that [a few colleagues] and I undertook a detailed study of the use of 100 commodities in the United States from 1900 to 2010," Ausubel wrote. "We found that 36 have peaked in absolute use…Another 53 commodities have peaked relative to the size of the economy, though not yet absolutely. Most of them now seem poised to fall."

A few years earlier, a writer and researcher named Chris Goodall had noticed something similar in the United Kingdom's Material Flow Accounts, "a set of dry and largely ignored data published annually by the Office for National Statistics," as the Guardian put it. He summarized his findings in a 2011 paper titled "'Peak Stuff ': Did the UK Reach a Maximum Use of Material Resources in the Early Part of the Last Decade?"

Goodall's answer to his own question was, essentially, yes: "Evidence presented in this paper supports a hypothesis that the United Kingdom began to reduce its consumption of physical resources in the early years of the last decade, well before the economic slowdown that started in 2008. This conclusion applies to a wide variety of different physical goods, for example water, building materials and paper and includes the impact of items imported from overseas. Both the weight of goods entering the economy and the amounts finally ending up as waste probably began to fall from sometime between 2001 and 2003."

Goodall was eloquent about the significance of dematerialization: "If correct, this finding is important. It suggests that economic growth in a mature economy does not necessarily increase the pressure on the world's reserves of natural resources and on its physical environment. An advanced country may be able to decouple economic growth and increasing volumes of material goods consumed. A sustainable economy does not necessarily have to be a no-growth economy."

I agreed with Goodall about the significance of economy-wide dematerialization, especially because the United Kingdom and the United States were the leading economies of the Industrial Era—a period that was defined by an unprecedented and extraordinary rise in the use of natural resources and other exploitations of the environment. If those two countries could reverse course and achieve substantial dematerialization, it would be a fascinating and hopeful development.

It would also be surprising, because it would mean that something fundamental about the mainstream understanding of how growth works would be incorrect. Most of us carry around an implicit or explicit belief that because humans always want to consume more, we will use more resources year after year to satisfy these wants. Technologies that allow us to make more efficient use of resources will not let us conserve resources, because we'll just use the technologies to let us consume even more—so much more that overall resource use will continue to rise.

This was the clear pattern until 1970. What could possibly have caused it to change? Moreover, if absolute dematerialization was a real and durable phenomenon, were there any interventions that individuals, communities, and governments could make that would help accelerate and spread it?

The Great Reversal

Fortunately for anyone interested in dematerialization, a lot of high-quality evidence exists about resource consumption over time in America. Much of it comes from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), a federal agency formed in 1879 and tasked by Congress with "classification of the public lands, and examination of the geological structure, mineral resources, and products of the national domain."

That examination of mineral resources is a boon to anyone interested in dematerialization, because since the start of the 20th century, the USGS has been collecting data on the use of the most economically important minerals in America. Of particular interest is the survey's yearly estimate of "apparent consumption" of each mineral.

This consumption takes into account not only domestic production of the resource but also imports and exports. For example, to calculate America's total apparent consumption of copper in 2015, the USGS would take the amount of copper produced in the country that year, add total imports of copper, and subtract total copper exports.

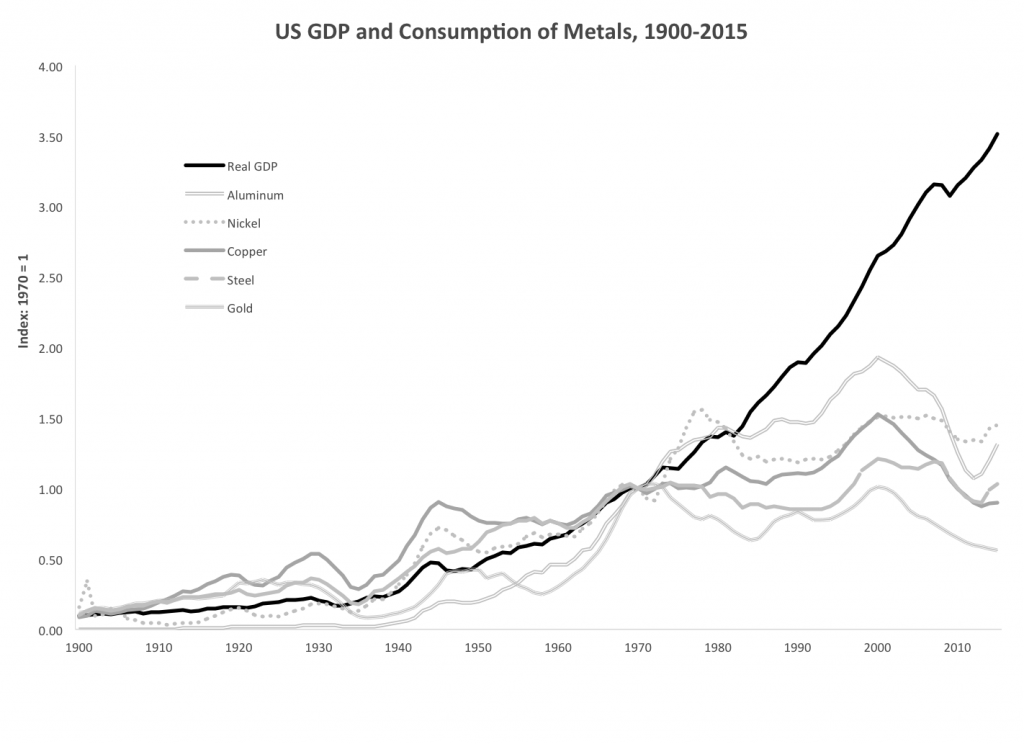

The survey's data tell a fascinating story. To understand it, let's start with metals, one of the most obviously important materials for any economy. Here's total annual consumption from 1900 to 2015 of the five most important metals in the United States. A reminder: This is not annual consumption per American. This is annual consumption by all Americans—the total tonnage used year by year of these metals.

All of these metals are "post-peak" in America, meaning that the country hit its maximum consumption of each of them some years ago and has seen generally declining in use since then. The magnitude of the dematerialization is large. In 2015 (the most recent year for which USGS data are available), total American use of steel was down more than 15 percent from its high point in 2000. Aluminum consumption was down more than 32 percent and copper 40 percent from their peaks.

This dematerialization becomes even more impressive when consumption of resources in the United States is compared to the country's economic growth. Note that a huge decoupling has taken place. Up to 1970, consumption of metals in America grew just about in lockstep with the overall economy. In the years since 1970, the economy has continued to grow pretty steadily, but consumption of metals has reversed course and is now decreasing. We're now getting more "economy" from less metal year after year. We'll see a similar great reversal in the use of many other resources.

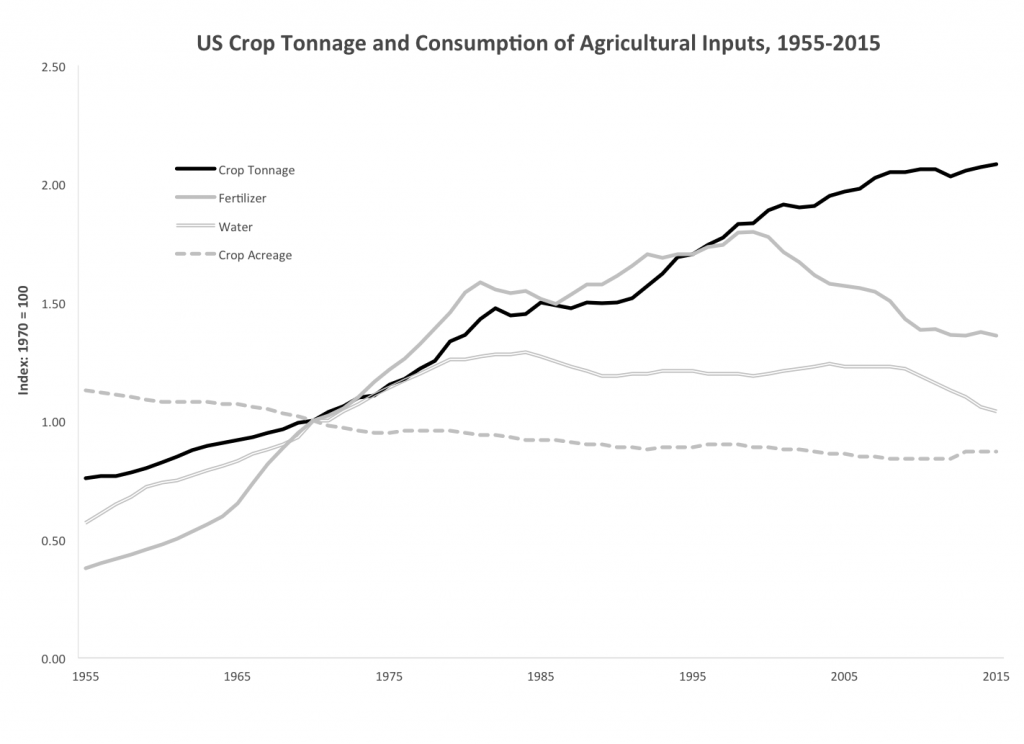

America is an agricultural powerhouse—the world's largest producer of both soybeans and corn and fourth-largest producer of wheat. Fertilizer is, as we've seen, essential for growing crops. So here's the country's total consumption over time of fertilizer, water, and cropland. Instead of GDP, this graph charts total U.S. crop tonnage.

Here again, output (crop tonnage) used to be tightly linked to inputs (water and fertilizer). But then that relationship changed, and we're now getting more from less. Fertilizer use is down almost 25 percent from its 1999 peak, and by 2014 total water used for irrigation had decreased by more than 22 percent from its maximum in 1984. Total cropland has also fallen, to levels rivaling the lowest points of the previous century.

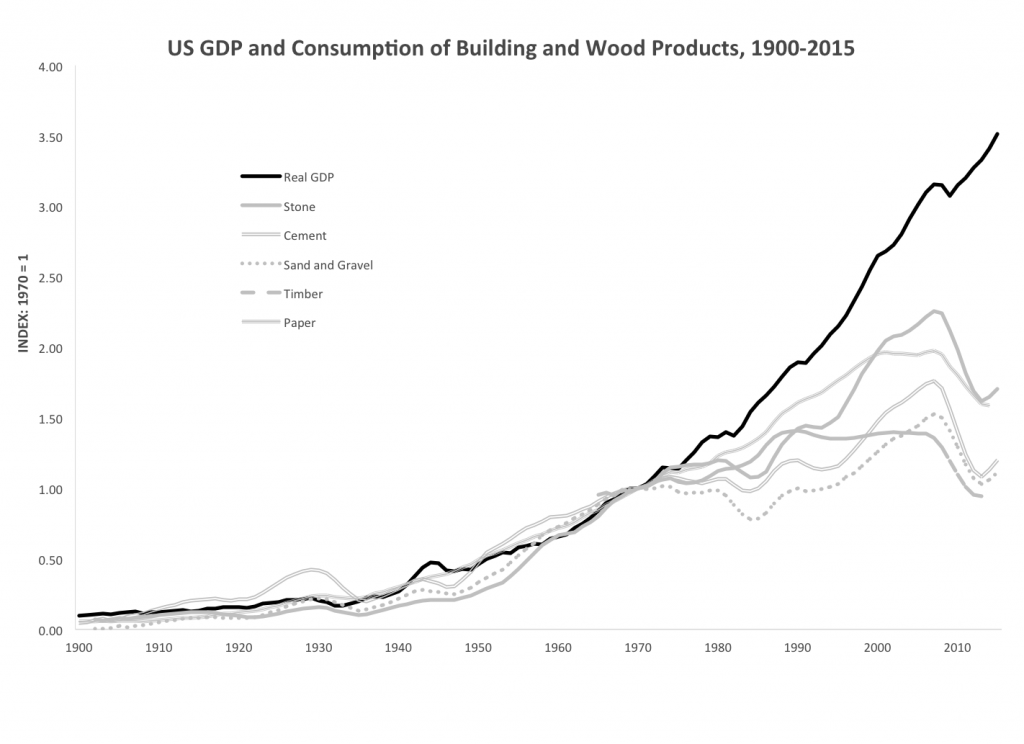

Building structures and infrastructure requires a lot of resources, so let's look at total consumption, according to the USGS, of the most important building materials. Let's also include data on timber use from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and throw in paper for good measure.

Here I see two different stories. The first is about building materials—cement, sand and gravel, and stone. Consumption of all of these peaked in 2007 and has dropped sharply since. But the sharp drop-off is surely because of the Great Recession, which hit the construction industries particularly hard. As construction recovers, we may find that we are not post-peak in these materials. But I predict that we're forever post-peak in our use of both wood and paper. Total timber use is down by a third and paper by almost 20 percent since their high points.

Are these graphs representative of what's been going on in the American economy as a whole? They are. Of the 72 resources tracked by the USGS, from aluminum and antimony through vermiculite and zinc, only six are not yet post-peak. Of these, we spend by far the most on gemstones. We Americans apparently have a bottomless thirst for bling. If shiny ornamental stones are excluded from the analysis, then more than 90 percent of total 2015 resource spending in America was on post-peak materials.

American consumption of plastics, which is not tracked by the USGS, is an exception to the overall trend of dematerialization. Outside of recessions, the United States continues to use more plastic year after year in the form of trash bags, water bottles, food packaging, toys, outdoor furniture, and countless other products. But in recent years, there has been an important slowdown.

According to the Plastics Industry Trade Association, between 1970 and the start of the Great Recession in 2007, American plastic use grew at a rate of about 5.2 percent per year. This was more than 60 percent faster than the country's GDP grew over the same period. But a very different pattern has emerged in the years since the recession ended. The growth in plastic consumption has slowed down greatly, to less than 2 percent per year between 2009 and 2015. This is almost 14 percent slower than GDP growth over the same period. So while America is not yet post-peak in its use of plastic, it's quickly closing in on this milestone.

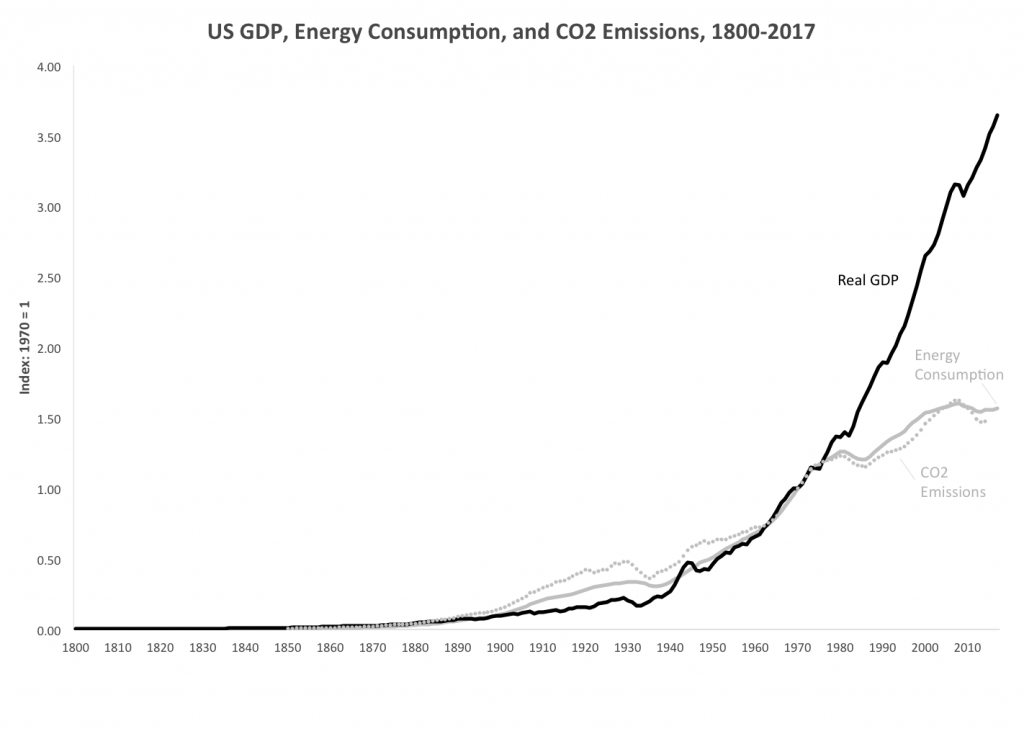

Finally, let's look at total energy consumption combined with greenhouse gas emissions, which are the most harmful side effect of generating energy from fossil fuels.

I was surprised to learn that total American energy use in 2017 was down almost 2 percent from its 2008 peak, especially since our economy grew by more than 15 percent between those two years. I had walked around with the unexamined assumption that growing economies must consume more energy year after year. This turns out not to be the case anymore—a profound change. Energy use went up in lockstep with economic growth in America for more than a century and a half, from 1800 to 1970. Then the increase in energy use slowed down, and then it turned negative—even as the economy kept growing. Over the last decade, we've gotten more economic output from less energy.

Greenhouse gas emissions have gone down even more quickly than has total energy use. This is largely because we have in recent years been using less coal to generate electricity and more natural gas, which produces 50–60 percent less carbon per kilowatt-hour.

The conclusion from this set of graphs is clear: A great reversal of our Industrial Age habits is taking place. The American economy is now experiencing broad and often deep absolute dematerialization.

Is the rest of the world dematerializing? It's a hard question to answer definitively because there's no equivalent of the detailed and comprehensive USGS data for countries other than America. There is evidence, though, that other advanced industrialized nations are also now getting more from less. Goodall, of course, found that the United Kingdom is now past "peak stuff." And Eurostat data show that countries including Germany, France, and Italy have generally seen flat or declining total consumption of metals, chemicals, and fertilizer in recent years.

Developing countries, especially fast-growing ones such as India and China, are probably not yet dematerializing. But I predict that they will start getting more from less of at least some resources in the not-too-distant future.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Someone needs to alert Greta.

It seems to me that several of the key presumptions modern Environmentalists hold (we are consuming more and more resources, the population is exploding) are not just inaccurate, but have been incorrect for several decades.

I may pick up this book, as I’m especially intrigued by the “what happens next” part in the sun-title.

You get what you pay for.

"In offices across from Seattle's Boeing Fiel, recent college graduates employed by the Indian software developer HCL Technologies Ltd. occupied several rows of desks, said Mark Rabin, a former Boeing software engineer who worked in a flight test group that supported the Max.

The coders from HCL were typically designing to specifications set by Boeing. Still, "it was controversial because it was far less efficient than Boeing engineers just writing the code," Rabin said. Frequently, he recalled, "it took many rounds going back and forth because the code was not done correctly."

Wow, good link, thanks!

Too much cost-cutting! Penny wise and pound foolish!

Out-take below...

"During the crashes of Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines planes that killed 346 people, investigators suspect, the MCAS system pushed the planes into uncontrollable dives because of bad data from a single sensor.

That design violated basic principles of redundancy for generations of Boeing engineers, and the company apparently never tested to see how the software would respond..."

PAY good pay for good, experience software writers, dammit!!!

The problem is hiring MBAs rather than engineers to run an aircraft company. The MBAs just saw the short term savings and lacked the technical knowledge and experience to see the long term problems it was created.

Airplane guys rather than accountants should run aircraft manufacturers. Somehow this piece of common sense has been forgotten by corporate America.

I agree. This is a problem with so many large technology corporations. Idiots with no technical knowledge making dumb decisions. The right way to do this it to pay for senior engineers to get MBA degrees and then to promote them to VPs.

But only if they meet the diversity objectives

Accountants ran GM from, world's biggest corporation to bankruptcy.

Cheap, good, or quick. You can have any two.

It may need updating to pick one.

It seems Boeing went for cheap and quick, but did not even pay enough for quick.

In my experience "good" is neither "cheap" nor "quick". If you're picking two of the three you're only getting "cheap" and "quick".

We had a similar experience. Estimates from outsourced coders are always cheaper because they do exactly what you tell them - no more, no less - without caring about the 'why' or how maintainable/testable the code is. In-house coders always estimate higher because they know it takes a few rounds to not only get it right, but get it maintainable/testable.

The coders from HCL were typically designing to specifications set by Boeing. Still, “it was controversial because it was far less efficient than Boeing engineers just writing the code,” Rabin said. Frequently, he recalled, “it took many rounds going back and forth because the code was not done correctly.”

I have some experience with that. Worked with a group from India from a company called Wipro. All highly certified. All highly credentialed. Deer in the headlights when anything went wrong. As a colleague of mine noted, "The manual tells you how to build it-- it doesn't tell you how to fix it when things go wrong."

I found the flaw in this rosy scenario:

"This consumption takes into account not only domestic production of the resource but also imports and exports. For example, to calculate America's total apparent consumption of copper in 2015, the USGS would take the amount of copper produced in the country that year, add total imports of copper, and subtract total copper exports."

Unless they are counting the copper (and of course every other commodity/material being evaluated) content of finished and semi-finished goods being imported, then, uh, this data and thus this article is useless.

I was going to comment the same thing. I’d all of these peaks and subsequent declines correspond with broad-based outsourcing of manufacturing to other countries, these figures may simply conceal continued increases in consumption. It would be good if Ron could clarify what the figures do or do not include.

Certainly electronics imports might account for some of the drop in metals consumption, but keep in mind the numbers we're talking about - 15, 20, 25% drops in tonnage We simply don't import that much and imports have not grown anywhere near those sorts of numbers. How many smartphones does it take to replace the Hondas we used to import but now build right here in the US?

That is a great point. And I don't think they are.

"Unless they are counting the copper (and of course every other commodity/material being evaluated) content of finished and semi-finished goods being imported, then, uh, this data and thus this article is useless."

Why isn't it safe to assume that manufacturers in other countries also avoid the expense of commodities and are also able to benefit from the productivity gains associated with new technologies--from manufacturing techniques, etc., as well?

Is there a Chinese manufacturer that prefers to use more copper when less copper will do just as well?

Is there a Chinese manufacturer that prefers to use more energy in their manufacturing when less energy would work just as well?

It's entirely possible that China is lagging the U.S. or Germany in terms of productivity gains associated with technology--because they're able to compete on the basis of their cheaper labor. Over time, however, they're subject to the same economic forces and cost avoidance incentives that drive manufacturing everywhere--and for all the same reasons.

The burden is on you to show that the force of gravity doesn't operate outside the border of the Untied States.

No, it's a fair question. If the imports measured are raw materials only, or only the obvious products like copper wire, what about electrical appliances (washing machines, dryers, ovens, toasters) and electronics which used to be made here?

I doubt electronics account for much copper at all, but appliances may. Those are mostly imported now. Cars use a lot of steel and now aluminum; were the increased imports of the 1970s partly responsible for the drop in usage? Now that the foreign car companies have a lot of local factories, did that boost the raw material imports?

A good question needs answers. We don't have them. Maybe the book does. Maybe import accounting does include iPhones and laptops.

Productivity gains are about using less resources to produce as much or more with the same amount of resources--be they natural resources like copper or other resources like labor.

Productivity gains are driven by the pursuit of profit, and they work the same regardless of where things are manufactured--so long as prices are set by markets and the profits go to private owners.

If American manufacturers are using less materials to build the same items (at less real cost) than they did over the course of the last 70 years, then that just confirms the obvious.

I know the idea that environmental concerns are best addressed by profit-driven capitalism is disappointing to socialists masquerading as environtmentalists, but to capitalist environmentalists like me, this data is simply confirming the same market fundamentals that have always been at work.

Incidentally, this is the same means by which capitalism and productivity gains drive increases in the standard of living. Increases in the standard of living are also about consumers being able to buy more or better for less cost. And from an environmentalist perspective, isn't it great to know that the choice between combating global warming and increasing our standard of living is a false dichotomy?

Not for socialists, no, but for people who care primarily about the environment and increasing our standard of living, that's great news.

While it's possible that finished-goods imports are skewing their data, the US exports only a trivial amount of our waste. By measuring waste, you can ignore the import skewing. As the article notes above, "Both the weight of goods entering the economy and the amounts finally ending up as waste probably began to fall from sometime between 2001 and 2003."

If waste is declining, (and we haven't yet perfected direct matter-to-energy conversion such that we can violate Conservation of Mass), then either we are holding things longer or the inputs are necessarily declining. I see no evidence to support the "holding things longer" hypothesis so the "inputs are declining" hypothesis seems more plausible.

"The Economy Keeps Growing"?

Not with Drumpf as President it doesn't! His tariffs and immigration restrictions have directly caused what Paul Krugman calls a global recession, with no end in sight.

#DrumpfRecession

Wow, you're such an idiot. Tariffs are taxes on foreign countries, it's free money! The billions and billions of dollars we're collecting are being used to pay down the national debt, which will totally be paid off in just a few more years.

Good job OpenBordersLiberal-tarian !!!

You are exactly correct! Canada has a FAR more open mind about bringing in hard-working and talented immigrants! Which is what you need for cutting-edge developments in AI, for example! So, American venture capital for this is now betting on Canada, not the USA! Thanks, Trump, you narrow-minded bigot you!

https://venturebeat.com/2019/10/05/why-we-moved-our-silicon-valley-startup-to-canada/

Why we moved our Silicon Valley startup to Canada

That's what happens when resource intensive manufacturing moves to other countries. We use less steel, energy etc, they use more.

Pretty much that. As Dan from Philly points out above, because it doesn't appear to count the materials in imported goods, this article is useless.

"A reminder: This is not annual consumption per American. This is annual consumption by all Americans—the total tonnage used year by year of these metals."

If American companies can manufacture more with less of these metals, I don't see any reason to believe that Chinese factories wouldn't behave the same way. Aren't they also price and productivity conscious?

We produce so much agriculture that we export it like the Chinese export manufactured goods. Isn't the technology that allows American farmers to increase their crop yields--despite using less fertilizer and less water--available in China and other countries, as well?

What we're talking about is increases in productivity due to things like technology in the broadest sense. As China's economy translates from having the productivity of medieval peasants to the productivity of the 21st century, I see no reason to believe that these productivity gains aren't happening in China or internationally.

P.S. Despite manufacturing making up less and less of a share of the total U.S. economy over the last 70 years, the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs is about where it was 70 years ago.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/manufacturing-employment-in-the-us-is-at-the-same-level-of-69-years-ago-2019-01-04

The fact is that those workers are a hell of a lot more productive than they were 70 years ago, and there are implications associated with that fact regarding how much in the way of resources are necessary for manufacturing, as well.

The Chinese just cut costs on labor. Force workers to live on premises in barracks then charge more in rent for the bunk.

And you imagine this means that they'd rather use more copper than less?

Do you or don't you imagine that manufacturers in China are immune to the same economic forces that drive productivity gains in other countries?

China's ability to compete on cost without using less copper in the present because their labor costs are lower does not mean that they wouldn't prefer to use less copper as well--when the technology to do so becomes available.

Do you understand how profit works? I'm not being condescending here--a lot of smart people don't really grok the implications of how profit works!

Profit is the difference between revenue and costs.

This is, for instance, the reason why profit driven companies can do things for less than government entities. A lot of Americans don't understand this. They think a profit of 10% means that the government could do the same thing for 10% less--because the government doesn't have to charge enough to cover a 10% profit. What they don't realize is that because the difference between revenue and costs is increased by cost cutting, cost cutting is the primary means of increasing profit--and the primary driver of most business decisions. Furthermore, you can't really control revenue like you can with costs--because revenue is driven by things like market prices, which are not only unpredictable but often beyond a company's control. I can shut down plants, lay people off, and decide not to grow to cut costs--it's far more under my control. It's also not clear that my competitors will raise prices if I do, so that's not my preferred way to increase profits at all.

The point is that because the difference between revenue and costs is increased when I cut costs, I am in a never ending struggle to decrease costs--and that is the primary driver behind manufacturers using less commodities like copper. And that is incentive to reduce costs through productivity gains and technology advances is universal in market based systems with private owners. Because China can compete on sales price using more copper than others because their labor costs are lower does nothing to change the fact that over time, they'd rather use less copper than more--because the less copper they use, the more they profit. The less copper they use, the more money that goes into their pockets--regardless of whether their labor costs are also lower.

As totalitarian state, China has little interest in maximizing productivity per worker or, in fact, educating its workers sufficiently to achieve high productivity.

The primary goal of the Chinese leadership is to stay in power. That's it.

That's nonsense. Their increased productivity is a fact. However it happened, there's nothing to indicate it has stopped happening.

"Totalitarian" is not all or none. There are degrees. And being totalitarian doesn't mean the rulers have no interest in efficiency or productivity. Even if all they care about is more taxes for their military, they still care.

Chinese GDP/worker is about 1/4 of that of the US or Europe. So, obviously, China isn't maximizing labor productivity. We want to explain that difference.

My explanation is that in order to reach European and US levels of productivity, workers and businesses need a great deal of autonomy and independence, autonomy and independence that is a threat to the Chinese leadership. So, they tolerate lower productivity in return for staying in power.

Your explanation for the difference between Chinese and Western productivity levels is... what?

"As totalitarian state, China has little interest in maximizing productivity per worker or, in fact, educating its workers sufficiently to achieve high productivity.

The primary goal of the Chinese leadership is to stay in power. That’s it."

The suggestion that the owner's of China's businesses aren't concerned with profits is absurd.

Meanwhile, much of China's industrial capacity is owned by former CCP members and officers in the PLA.

Well, and I didn't suggest that. I suggested that "China's leaders" aren't primarily concerned with profits, they are primarily concerned with staying in power.

It's the accounting which matters. If appliances and electronics are now imported instead of being made domestically, the question is whether those imports are counted among the raw materials. It's an entirely valid question. You can't just wash it away by saying the same manufacturing efficiencies apply in China. For one thing, this may not be a question of manufacturing efficiency, it may be a matter of buying less. If washing machines last longer, is that where the reduced waste comes from?

For another thing, if copper in imported appliances is not accounted for, then the actual import record is artificially low and distorts the accounting.

"It’s the accounting which matters. If appliances and electronics are now imported instead of being made domestically, the question is whether those imports are counted among the raw materials."

No, it isn't.

The question is whether any particular manufacturer is lowering its costs by increasing its productivity over time. Then the question is whether those same forces are at work on other manufacturers for the same reasons.

Force = Mass * Acceleration

In the U.S., in China, in Germany, and in Mozambique, when you drop a hammer on your foot, the same thing happens for the same reasons--in all of those countries.

If a study is able to show that general rule at the national level it confirms the general rule we've known all along.

It is not necessary to observe every water molecule in every ocean at the same time in order to conclude that they all pretty much have two hydrogen molecules and an oxygen molecule. We know what makes something H20, and we know why it becomes a water molecule. And the idea that we don't really know whether the general rules of hydrogen dioxide are true because we haven't observed every single water molecule on earth at the same time is to willfully embrace ignorance.

Everywhere we've looked, we've seen productivity gains for the same reasons. If you believe that f=ma doesn't work in China, it's incumbent on you to show us not only the data--but why it's different.

Poor analogy. Because the law you want to apply everywhere has applied in the US only since about 1970. So it isn’t a law. It’s a conditional outcome from other factors. We can’t just wave our hands and say it’s clearly at the same point in the curve in China unless we know that the incentives are the same there.

And the article is very up front that we simply don’t know (and likely *can’t* with present data) the things you are assuming. Basically your argument is that things should be the same in China and so they must be. The rest of us are asking the legitimate question whether they are with assuming the answer in advance.

It may be that you’re right, but you’re far from proving it. Given that you’re assertion would have been wrong for most of the history of the US, it’s not obvious it would be right elsewhere in the present.

"Poor analogy. Because the law you want to apply everywhere has applied in the US only since about 1970. "

The law that productivity gains are a profit driven process by which market economies create increasingly more and better with a smaller and smaller amount of resources--has only applied in the U.S. since about 1970?

Um . . . no. Companies have been competing to make more and better products with fewer and fewer resources since long before banks and others started replacing people with ATMs, farmers started replacing oxen with tractors, and steam engines were first put to work in factories. It started before farmers started replacing hoes with plows. Increases in productivity have been driven by the same market forces and for the same reasons since shortly after the first farmers in Sumer decided to stay in one place and irrigate.

I wish I were the first guy to notice productivity gains and what makes them happen, but I'm not. And that's what we're talking about--why and how we keep making more and better things with less and less resources for lower and lower real costs. There are reasons why that happens, reasons I've already alluded to, and they've always been the same cross culturally and throughout history--and that's what makes something a universal rule.

F=ma (at sea level) also works cross culturally and throughout history.

Despite what you see with your own lying eyes, the fact is that we can't have both market driven economic growth and progress on climate change, and we know this because scientists and socialist politicians say so. In fact, only scientists and socialist politicians can command the kind of authority we need them to have in order to force us to make the kinds of sacrifices in our standard of living that are necessary if we're to avoid climate change driven threats to our standard of living. And if you don't understand that, you are so uncool.

"Real GDP"

If we print enough money, we can also create a perpetual motion machine.

Modern Monetary Theory FTW!

Cool Status

Read this carefully

read this carefully

Generally, yes, production processes get more efficient.

The article is still confusing economic growth with "getting more for less" and using hare-brained accounting schemes for the inputs into production. If you want to quantify how much more efficient production has become, you can't do it with this kind of bogus reasoning.

We may be consuming less paper overall, but the lady in front of me took 8 (eight) napkins at lunch. For a salad. It was a struggle not to ask her if she was going to bathe in the dressing.

Perhaps I missed something, but after 1970 we imported much more stuff, so our purchase of raw aluminum here may be down but we're importing many commodities which contain aluminum which was mined offshore.

Sell your Kidney for a good amount of $80,000.00/- from 14lahk to 10 crore Indian rupees all blood groups are needed at hope hospital call or Whatsapp us +918970196553

"We’re getting more while using less."

If this won't piss off all the progressive shitheads, nothing will.

E=mc^2

Someone should introduce the author to the idea of "service economy". Gosh, you mean a hedge fund consumes less steel than a small appliance factory? Shocking!

Which just makes all the climate reactionaries here even funnier.

Excellent article. Keep writing such kind of information on your blog.

Im really impressed by it. marijuana for sale

You’ve performed a fantastic job. I’ll definitely

digg it and for my part recommend to my friends. I’m confident they’ll be

benefited from this web site. marijuana for sale

buy marijuana

buy marijuana online

marijuana for sale

order weed online

buy cannabis online

cannabis for sale

buy real weed online

weed for sale online

order marijuana online

where to buy weed online

order cannabis online

weed shop online

where can i buy weed online

buy cannabis

online weed store

marijuana for sale online

marijuana online store

marijuana buy online

weed buy online

buy pot online

cannabis online shop

weed online for sale

buy real marijuana online

online weed shop

real weed for sale

cannabis for sale online

weed store online

buy legal weed online

marijuana online shop

buy weed online cheap

purchase weed online

buy real weed online cheap

purchase marijuana online

order real weed online

weed online store

Order dank vapes online

Where to order dank Vapes online

Dank vapes for sale

buy dank vapes online

marijuana cartridges for sale

Why is this a surprise? Just look at modern vehicles, there's more plastic, carbon fiber, etc. Modern metal alloys are stronger than older alloys and digital simulation allows stronger structures to be built with much less material. Look at how much went into designing modern beer cans to get the wall thickness to the bare minimum and saves literally tons of aluminum in the process.

We may be consuming less paper overall, but the lady in front of me took 8 (eight) napkins at lunch. For a salad. It was a struggle not to ask her if she was going to bathe in the dressing.

مشکلات دوران نوجوانی

This is the miracle of increasing efficiency of production. It not only lowers resources needed, but lowers final prices as well. Efficient production makes all our lives better... and unfortunately, that includes the communists who are trying to destroy it as well.