The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Stairway to Heaven and the Scope of Musical Copyright

Led Zeppelin may have borrowed from the band "Spirit" in creating the well-known intro to their classic hit, but did they infringe anyone's copyright in doing so?

Last week the en banc 9th Circuit heard argument in the case of Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, involving the claim that the famous opening guitar riff in Led Zeppelin's classic "Stairway to Heaven" — No. 31 on Rolling Stone's "Top 500" list (overrated, in my view) and, as New Yorker music critic Alex Ross put it in his excellent summary of the issues in the case, "the stuff of a million teen-age guitar lessons" — infringed the copyright in the song "Taurus," released two years before "Stairway" by the band Spirit. The suit is being brought** by the estate of Randy Wolfe, a.k.a. "Randy California," lead guitarist in Spirit and the author of "Taurus."

[**Full disclosure: Plaintiff's lawyer, Francis Malofiy, was a student of mine some years ago at Temple Law School, though he and I have not stayed in touch or had any communications about this case.]

This case has been around for about five years, and I've blogged about it before. [See here and here]. You can listen to the two songs (the relevant portions are at 0:40 - 1:05 of Taurus here, and the first 25 seconds of the allegedly infringing Stairway, here).

Undeniably, there is a considerable degree of similarity between the two***; whether this constitutes infringement or not, though, is a tricky question. Led Zeppelin prevailed after a trial in the district court; the jury found there was no infringement, but on appeal the 9th Circuit panel reversed, leading to this en banc proceeding to consider whether that reversal was proper. [The rather complicated procedural history of the case is described in defendants' Petition for Rehearing en ban, available here].

***Tangentially, you might wonder why, if the alleged infringement took place in 1971 and involved one of the best-known and oft-played songs of all time, it took the plaintiff so long to levy the charge of infringement? I have no inside information on that, though I would note that this suit is not being brought by any of the musicians in Spirit or by the author of the allegedly infringed work (Randy Wolfe), but by the estate of the (now-deceased) author on behalf of his heirs. This is a common phenomenon in copyright infringement cases, and one that I have highlighted before. Much of copyright law involves claims by what are called "residual legatees" - heirs and such - rather than by the supposedly wronged artist, who might value the ethos of sharing that is quite strong among working musicians considerably less than they value the expectation of a financial windfall.

And speaking of dates, you might also be wondering why this claim isn't barred by the statute of limitations, given that the alleged infringement took place 43 years before the filing of the lawsuit. If the members of Led Zeppelin had set their hotel on fire in 1971, injuring dozens of people, and then submitted false information to their insurance company to recover on their damage claim, the statute of limitations would long since have expired, barring any claim against them any liability for their actions in 2014. But there's a funny thing about copyright law. There is indeed a statute of limitations (three years) in copyright law, but because Led Zeppelin still distributes copies of the allegedly infringing work and earns royalties from that distribution, the infringement is considered a "continuing" one, occurring every time a radio station plays Stairway or someone streams or downloads a copy of it, so the time period for bringing a claim has not expired (and probably never will).

There is an important*** - and to my mind dispositive - issue in the case that the court is being asked to resolve: What, exactly, does it mean to say that Randy Wolfe has copyright in "Taurus"? To what elements of that composition does his copyright extend? What, in other words, can he lawfully prevent others from appropriating from his work? Is it just the notes constituting the descending chromatic bass line and the accompanying chords? Or does he own copyright in the overall sound of the song as Spirit recorded it - involving the use of a single acoustic guitar played in a fingerpicking style, the lush string accompaniment, the use of flute and harpsichord in the background, etc.?

*** One of the unusual features of this case is that the US DOJ has weighed in with an amicus brief is support of the defendants [available here]. It is not entirely unprecedented, but the government rarely intervenes in a private lawsuit alleging copyright liability unless, in its view, important questions about statutory interpretation have been raised. Bloomberg News had a rather breathless article claiming that this shows that the Trump Administration "wants to blow up copyright" - not true at all, but it does suggest that they think (correctly) that the outcome of this case does really matter for the future of copyright protection.

This is critical in this case, because so much of the similarity between the two songs involves these accompanying elements in the performance of the songs, which make the two songs sound alike. Not surprisingly, the plaintiff argues that these elements are included within Wolfe's copyright, and that Led Zeppelin's appropriation of these performance elements is therefore infringing.

The district court disagreed. The court held that the plaintiff could not rely on these performance elements that can be detected in recordings of the song (or that would be present in live renditions) - the "fingerpicking style, acoustic guitar, classical instruments such as flute strings and harpsichord, atmospheric sustained pads and fretboard positioning," along with the "music production and mixing process [which] created a common ethereal ambience" in the two songs - to demonstrate infringement, because those "performance elements" were not reflected in the sheet music that Wolfe submitted to the Copyright Office in order to obtain his copyright. Plaintiff's effort to demonstrate the similarity between Taurus and Stairway to Heaven was, the court held, limited to "the protected elements of the song embodied in the deposited sheet music."

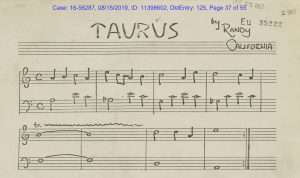

Two features of this holding - the correct one, in my opinion - bear emphasis. First, that Wolfe's copyright only extends to elements "embodied in the deposited sheet music." A little copyright history is necessary here. Because Wolfe's song was composed before the 1976 Copyright Act was enacted, the scope of his copyright was governed by the earlier, 1909 Act. Under the 1909 Act, copyright in a musical work was dependent upon submitting an application to the Copyright Office along with a copy of the work in "visible notation" form. A performance of the work was not an acceptable deposit (because, among other things, performances of musical works were not themselves protected by copyright); only sheet music or the equivalent could secure the copyright.

The relevant portion of what Wolfe submitted in 1968 to secure his copyright is reprinted at the top of this article, reproduced from the original copyright filing. The sequence of notes depicted there, in the "deposit copy," the court held, is all that Wolfe's copyright covers. The performance elements - the strings, the mix, the flute, the fingerpicking style of play, etc. - are not protected by copyright, and therefore cannot be the basis of infringement liability.

The court continued: "Once all the unprotected performance elements are stripped away, the only remaining similarity [between Taurus and Stairway] is the core, repeated A-minor descending chromatic bass line structure that marks the first two minutes of each song."

That should have been enough to grant summary judgment to the defendants, because of the other part of the court's holding: that not everything in the deposited sheet music is included in Wolfe's copyright, but only the protected elements therein. The fundamental axiom of copyright law is that only original components of a work are protected, and once you strip away the performance elements from this work and look only at the work set forth in the sheet music, there's nothing remotely original about it. Alex Ross in the New Yorker has examples of everything from Bach's E-minor Bouree through Chim-Chim-Cheree (from Mary Poppins), the Beatles' Michelle and While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Dylan's Ballad of a Thin Man, and the Eagles' Hotel California, all of which use the same chord progression as that denoted in the deposited sheet music.

The Ninth Circuit has a particularly convoluted jurisprudence regarding the evaluation of infringement claims, requiring courts to apply an "extrinsic" and an "intrinsic" test to determine infringement, tests that one of my colleagues, expressing what I think is the consensus opinion among copyright lawyers and law profs, described as "indecipherable." One hopes that they use this case to simplify and straighten out their doctrine.