Bill de Blasio's Proposed 'Robot Tax' Is Completely Unnecessary, Just Like His Candidacy

Forcing future Americans to do manual labor that could be automated isn't "saving" them from job losses. It's trapping them in jobs that could be made more efficient, more productive, and more rewarding.

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio's latest attempt to jump-start his inert presidential campaign includes a call for a new federal tax on robots. This unnecessary burden on businesses would expand the federal bureaucracy and fund boondoggle projects, and it is based on a faulty understanding of the relationship between jobs and automation.

In an column published last week by Wired, de Blasio outlines how his "robot tax" (his words) would work. Businesses that "eliminate jobs through increased automation" would be required to pay five years of payroll taxes, up front, for every employee replaced by a robot, de Blasio says. That tax revenue would be used to fund government make-work projects (not his words) in health care, the environment, and other areas.

"Displaced workers would be guaranteed new jobs created in these fields at comparable salaries," de Blasio writes. "A 'robot tax' will help us create stable, good-paying middle-class jobs for generations to come."

The tax plan comes with a new bureaucracy to regulate automation in the workplace: the Federal Automation and Worker Protection Agency, which would be in charge of determining which jobs were eliminated by automation and how much "robot tax" employers would owe.

"A worker pays income tax. You take away millions and millions of workers, that's a lot less revenue to take care of all the things we need in our society, and it means, of course, millions and millions of people don't have a livelihood," de Blasio explained during an appearance on Fox News. Tucker Carlson nodded along as de Blasio said automation "could be the single most disruptive force in our society that we've ever experienced."

It's true that automation could disrupt to the American workforce significantly in coming years, but de Blasio—and others, including fellow Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, who has centered his campaign on fears of automation-driven unemployment—is likely overstating the negative effects. Machines have been replacing manual labor literally for centuries, and that process has made society richer, safer, and healthier.

As technology advance, human jobs don't disappear—they just change. The advent of the automobile meant there were fewer jobs in the carriage making and blacksmithing professions, but it created a host of new opportunities on assembly lines and in mechanic shops. The very blue-collar jobs that de Blasio wants to protect from automation were the result of a similar tech-driven disruption in the past.

Proposals like de Blasio's are based on the notion that the current iteration of widespread automation is a greater threat than similar events in the past. Some studies seem to back that claim. De Blasio points to a Brookings Institution paper estimating that 36 million American jobs are "highly likely" to be automated in the next few decades. Another oft-cited study is a 2013 survey from Oxford University showing that nearly half of all jobs in the United States are at risk of being automated away during the next two decades.

But other studies suggest those fears are overblown. In 2017, the Centre for European Economic Research, a German think tank, found that the "automation risk for U.S. jobs falls from 38 percent to 9 percent when allowing for workplace heterogeneity." That's because "the majority of jobs involve non-automatable tasks" and "workers of the same occupation specialize in different non-automatable tasks."

In other words, many workers won't be displaced; they'll simply take on different roles as parts of their jobs are automated. That makes a lot of sense. The automation of publishing—the very thing that allows you to read this article on a website instead of on a piece of paper stamped by a handset typeface—allows writers and editors to do different tasks and to work more efficiently.

Automation doesn't just change how work is done; it actually creates more jobs than it destroys. As Reason's Ron Bailey explained in a 2017 feature:

When businesses automate to boost productivity, they can cut their prices, thus increasing the demand for their products, which in turn requires more workers. Furthermore, the lower prices allow consumers to take the money they save and spend it on other goods or services, and this increased demand creates more jobs in those other industries. New products and services create new markets and new demands, and the result is more new jobs.

Or consider what's happened in the past few years. American companies installed more robots in 2018 than in any previous year, but the addition of more than 28,000 automated workers last year did not cause unemployment to spike. In fact, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of Americans working hit an all-time high.

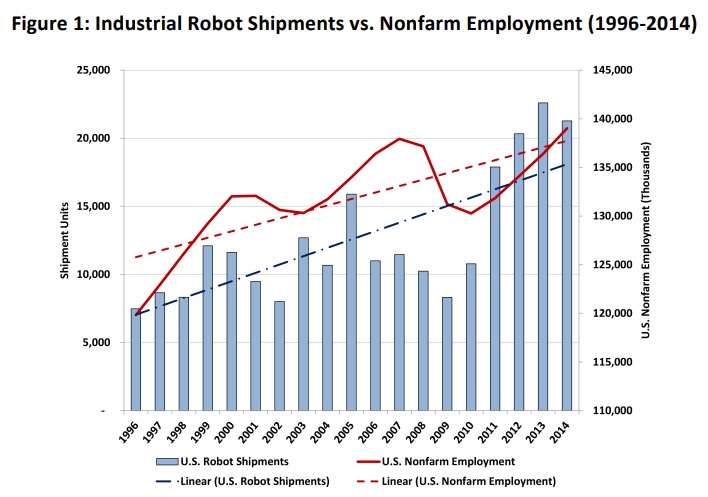

"The world economy continually faces this cycle of disruption and reinvention. Yet we have more people working today than at any point in history," writes Robert Huschka, director of strategies at the Association for Advancing Automation (A3), which tracks the number of robots involved in the American workforce. According to A3, the use of robotics in the workplace parallels overall employment trends—which is not what you'd see if robots were replacing workers on a large scale:

There's no doubt that more advanced robots and the development of artificial intelligence will change how Americans work. But there's nothing to suggest that this is a problem requiring an expensive new federal program. De Blasio's "robot tax" is a desperate attempt by a flailing candidate to achieve some level of relevance by selling an economic panic.

From check-out scanners to MRI machines, robots have made us better off. Forcing future Americans to do manual labor that could be automated instead isn't "saving" them from job losses—it's trapping them in jobs that could be made more efficient, more productive, and more rewarding.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Skynet started as a Sovereign Citizen, you know.

The sad thing is the widespread assumption that the only value a company has is the tax it pays.

Well, no. Don’t forget about the campaign contributions.

They’ve gone far past that on the left. Not only the tax they pay but want to dictate where they spend their after tax money. Essentially private ownership of a company but none of the rights and freedoms of ownership remain.

There’s a word for that.

“A worker pays income tax. You take away millions and millions of workers, that’s a lot less revenue to take care of all the things we need in our society, and it means, of course, millions and millions of people don’t have a livelihood,”

At least he has the priorities straight.

This is how you get robots to join the libertarian party.

De Blasio would probably have supported laws against automatic mobile devices so as to preserve the horse and buggy industry and related jobs.

I see what you did there.

That’s essentially what FDR did to try and save the family farm. Meant everyone else in the depression had to pay higher prices for food. Nice guy to force those struggling to pay more for basic necessities.

I will enthusiastically vote for whoever gets the Democratic nomination in 2020 (unless it’s Tulsi Gabbard), but I can admit when Democrats have bad ideas. And the “robot tax” is certainly a bad idea.

To guarantee good jobs and economic prosperity, what we really need to do is implement the late David Koch’s vision of a United States with unlimited, unrestricted immigration and no minimum wage.

What an asshat

And I am assured that the ‘real’ unemployment rate is 15-20% *right now*.

This may be closer to true depending on how you rate the massive rise in “disability” claims.

Although I doubt it’s as high as 15-20%. Here’s a graph which takes several “broad” measures of unemployment, rated at “U1-U6”. According to the graph, the broadest measure (U6) had an unemployment rate of ~11% in 2015 with a high of ~17% in 2008-09. U5 which is probably a little more realistic showed an unemployment rate of ~10% in 08-09 and was down to ~7% in 2015.

Make of that what you will.

Just found the latest statistics which show the U6 rate to be ~8% in 2019.

I would love an actual breakdown of how many blacksmiths went out of business because of the automobile. The fact is that blacksmiths were already mechanics. The industrialization of the latter 19th and early 20th century required blacksmiths to learn mechanics. Your steam thresher broke down in central Montana, who was qualified to fix it? The blacksmith. Many blacksmiths transitioned to mechanics, especially in rural areas because they had the basic knowledge already. They were the ones relied upon to fix things already.

I believe that is part of the point Boehm is making

That’s because “the majority of jobs involve non-automatable tasks” and “workers of the same occupation specialize in different non-automatable tasks.”

In other words, many workers won’t be displaced; they’ll simply take on different roles as parts of their jobs are automated.

When the only tool in your political toolbox is a tax, then everything looks like it’s taxable.

Also…

> A worker pays income tax. You take away millions and millions of workers, that’s a lot less revenue to take care of all the things we need in our society

Your make work scheme funded through taxes is going to a tax on the tax, a net revenue loss. It’s like using a fan to power the wind turbine used to generate the electricity used to power the fan.

The obvious solution to revenue loss due to fewer jobs is to STOP putting impediments in the way of job creation. Duh.

Or like the old cartoons whether the big bad wolf huffs and puffs on his sail to scoot along.

Or the Florida Man who put a sail on his airboat…

But Mythbusters proved that works.

The ‘best and brightest’ in this country sure are the dumbest human beings on the planet.

It’s also exhibit A as to why even when one recognizes disruptions in the economy and labor markets, the solutions are almost always worse than the problem.

I would Recommend that Bill DeBlaze’s campaign should hire a typing pool as a way to disseminate all communications from hereon out.

There are 2 dudes in that pic. I wonder if they had any trouble getting a date.

Even very liberal New Yorkers will concede that Bill de Blasio is several steps removed from the best and brightest.

http://pjmedia.com/parenting/open-letter-to-the-gender-confused-dude-in-the-beard-and-lipstick-my-kid-is-going-to-stare/

Dear Gender confused dude in the beard with the lipstick, my kid is going to stare.

And so will everyone else.

John, it’s your fault for not exposing your kid, from birth, to every hobby, fetish and life choice any other human has ever made so that your kid will be used to that stuff. It’s also your kid’s fault for not realizing how problematic your attitude is and taking it upon xerself to educate xerself in the woke arts.

New Yorkers deserve what they get for electing this progressive turd.

The problem with the anti-fearmongering argument is that there is something to be afraid of; automation works out in the long run, but what about the short run that we all have to live in with tens of millions of people out of work and too old to be retrained? Or too poor to re-enter the job market? Anyone who has studied the history of economics knows that substantial technological revolutions have always resulted in societal upheaval, violence, luddism, etc.

It might sound wild, but look into late 17th century history and see how guilds reacted to technological developments. They literally dispatched assassins, murdered inventors, and destroyed their inventions. Read Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers for a fun history lesson on that one.

No one is too old to be retrained or too poor to re-enter the job market. The only thing to fear is government intervention.

You’re missing the point, awild. The guild reactions are analogous to DeBlasio’s reactions – counterproductive, wrong and wildly out of proportion to the actual disruption. Most of the societal upheaval during the period you’re talking about was the result of urbanization, not of automation.

By the way, the number of those “too old to be retrained” was and is approximately zero. Everything we know about adult learning confirms that you’re never too old.

And I don’t even know how you could be “too poor to re-enter the job market”. The desperately poor enter the job market every day. There is no lower threshold below which you’re not allowed in.

A robot tax is obviously absurd, unlike completely sensible robot insurance from Old Glory Insurance. When they grab you with those metal claws, you can’t break free, because they’re made of metal, and robots are strong.

Bloop bleep de-doop, NO TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION, beep beep de bleep.

This is really funny coming from a guy whose other policies are overwhelmingly driving the shift to automation.

“The tax plan comes with a new bureaucracy to regulate automation in the workplace…”

“Government’s view of the economy could be summed up in a few short phrases: If it moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it.”

~~Ronald Reagan

Can subsidies be far behind?

Dang, where was De Blasio when we needed him? Had he been around a little more than a century ago we would still have cheap buggy whips.

If you recall De Blabio wanted to get rid of horses and buggies his first term. One more term he’ll be calling to subsidize the sedan chair industry.

What we need is a law forcing employers to pay robots wages, and then we can tax those wages at say 99.99% (because robots are stupid) easy peasy, duh then we can just hang out at the beach relaxing and reaping the rewards

This piece of shit is an admirer of Robert Mugabe. Fuck him.

-jcr

“Automation doesn’t just change how work is done; it actually creates more jobs than it destroys.”

This is simply BS. “Work” is not an undifferentiated mass. Some functions get automated. Some do not.

Similarly people are not an undifferentiated mass. Not everyone can be a brain surgeon or a super model. As machines take over more and more functions, more and more humans can’t compete.

Muscular labor get automated. Physical labor gets automated. Intelligent labor gets automated.

While women’s rates climed steadly from the 50s to 2000, they have slipped since, never reafching male rates.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS11300002

Labor Force Participation

The overall Labor Force Participation Rate has fallen to levels not seen since around 80, before women fully entered the work force, and currently are significantly below the rates seen through the 90s.

https://goo.gl/PHK7Y1

Male labor participation rates are at all time lows, down about 20 points from 1950. The steepest period of decline for males rates was 2008-2014. It’s been flat since, but the next economic shock likely produces another big drop. The rate has never had a sustained increase.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS11300001

Labor Force Participation

The overall Labor Force Participation Rate has fallen to levels not seen since around 80, before women fully entered the work force, and currently are significantly below the rates seen through the 90s.

https://goo.gl/PHK7Y1

ultravnc viewer likes this post

Cut Bill some slack. At least he’s willing to tax himself.

Just when you think a politician can’t come up with a dumber idea they do. So, DeBlasio would be against robots eliminating dangerous jobs.

Reminds me of the story of Milton Friedman who went to China and saw the infrastructure projects being done with laborers with shovels. He asked why not have heavy machinery to be more efficient, and the answer was to create jobs. Friedman’s response was if that’s the case why not have them work with spoons?