Hells Angels Meet Housewives on Harleys

How bikers turned into their parents and turned off their kids

On a rainy night in 1974, Charles Umbenhauer pulled his Yamaha motorcycle into the parking lot of a hotel in New Jersey so that he and his wife could wait out the storm before finishing their ride from his hometown of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to the Jersey shore. The front desk clerk would let them stay under one condition.

"If you push the motorcycle up the street there and it's not in the parking lot, I'll go ahead and rent you a room," Umbenhauer recounted in 2008 to American Motorcyclist, the membership magazine of the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA).

The request stung Umbenhauer, who had served two years in the Army and considered himself an upstanding citizen. He and his wife, Carol, said no thanks. Instead they found a "really crappy" hotel that allowed them to keep their bike in the lot. A couple of years later, when a friend invited the couple to attend a new motorcycling group's first rally for their rights at the Pennsylvania State Capitol, Charles and Carol hopped on the bike and went.

This was the '70s, and bikers faced discrimination not just from fearful business owners but also from state and federal governments. A group called MAUL—Motorcyclists Against Unfair Legislation—wanted to broker a truce with lawmakers to oppose helmet laws and other restrictions. The coalition drew motorcyclists of all kinds. In particular, the wrong kind.

"We went to the rally, and I knew it wasn't going to work," Umbenhauer says. For starters, the group had shown up to the state legislature on a Sunday. "People were streaking, there were beer kegs, but there was no legislative session. I gave it a 10 on having a great time but a zero on doing something to benefit bikers." The Associated Press reported the morning after that one motorcyclist rode around the rally naked "except for black socks" and that several riders had burned their helmets.

Umbenhauer voiced his concerns to other MAUL members, and they asked him to organize their next trip to the statehouse. His first act was to hold the event on a Monday. "I said we're gonna do it when the legislature is in session, and someone said, 'Half these people won't come.' And I said, 'Good. We don't need people drinking beer on the Capitol steps.'"

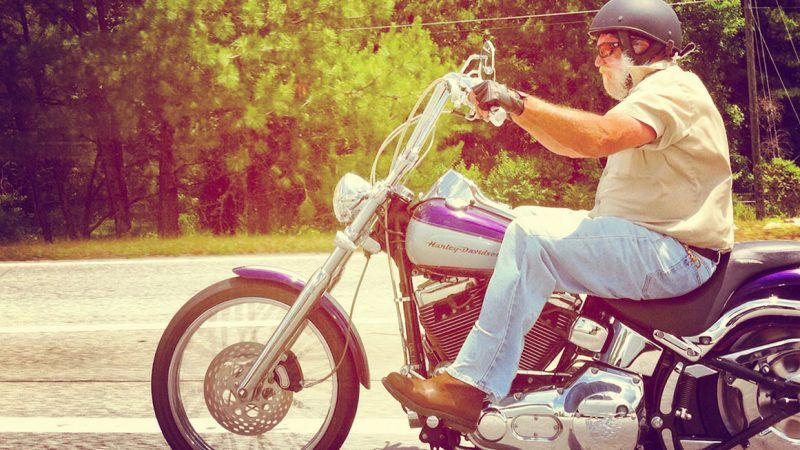

Over the next 40 years, Umbenhauer, now 74, and his fellow bikers organized, professionalized, and lobbied their way to legitimacy. But the victory has been bittersweet. Motorcyclists have more freedom than ever, but the gains they fought for are going to waste. Whether legitimacy has made motorcycling uncool or safety has simply become more of a priority, young people just aren't becoming bikers. "My grandson," Umbenhauer says, "doesn't ride."

Motorcycle interest groups are almost as old as motorcycles. Munich's Hildebrand & Wolfmüller began mass-producing motorrads in 1894. During the next 10 years, engineers in the United Kingdom and the United States followed suit, launching such iconic motorcycle brands as Triumph, Indian Motorcycles, and Harley-Davidson. These new machines—not as big or as fast as cars, far more powerful than bicycles—drew fans and haters alike.

"The peculiar character of the motor bicycle has left its status open to various definitions, and as a result in many states…the laws applying to big motor cars are brought to bear on motorcycles with oppressive force," reads a notice published in The New York Times on August 24, 1903. Authored by the leaders of the Alpha Motor Cycle Club and the New York Motor Cycle Club, the notice likely referred to the patchwork of road laws then governing gasoline-powered vehicles, which were considered a nuisance. Some cities required vehicles to have hand-operated noisemaking devices that drivers were supposed to honk and ring whenever they drew near pedestrians. Other cities weren't sure whether to treat motorcycles like pedal-powered bicycles (which they closely resembled) or like cars.

New York riders wanted to protect themselves as cities and states figured out new rules for the era of gasoline. "One cannot freely pass from one state into another without fear of arrest because of such laws," the notice continues. "To combat such measures, to insist that the highways are free to all alike, and that the right to use them is irrevocable, is one of the objects to be served by organization." They would go on to name the new group the Federation of American Motorcyclists.

By 1910, motorcycles were coming into their own as a feature of daily American life. Motorcycle cops chased down baddies, adrenaline junkies broke speed records, and the U.S. military learned biker messengers were twice as fast as riders on horseback. After visiting the 1910 motorcycle trade show in Madison Square Garden, the Times' C.F. Wyckoff declared that these "little distance annihilators" had graduated from the "poor man's automobile" to a "pleasure vehicle" and a "utility vehicle."

Through the '20s, '30s, and '40s, motorcycles made headlines for miraculous feats ("MOTORCYCLISTS ON WAY: Two Argentinians Reach Mexico City En Route to New York"), for upsetting the apple cart ("Town Hunts Motorcyclist; Broke 30-Year Sabbath Calm"), and for their role in daily life ("DOG TRAILS MOTORCYCLISTS; Hunts for Dead Owner, Killed in Crash"). Much ink was spilled on accidents, but the same was true for cars back then. All of which is to say that motorcycle culture was considered an anodyne subgenre of sporting and adventure.

That assessment began to change toward the end of World War II, when some American veterans started riding stateside for camaraderie and to escape the disorienting placidity of post-combat life. "Searching for relief from the residual effects of their wartime experiences, [veterans] started seeking out one another just to be around kindred spirits and perhaps relive some of the better, wilder social aspects of their times during the war," William Dulaney wrote in a 2005 issue of the International Journal of Motorcycle Studies. Former American airmen even brought their wartime style to motorcycling: leather jackets to protect them from the elements, goggles to protect their vision.

The nonrider view of bikers changed permanently for the worse when the Pissed Off Bastards of Bloomington and the Booze Fighters Motorcycle Club showed up at a hill-climbing event in California hosted by the AMA in 1947. Other rowdies showed up as well, and together the interlopers supposedly shocked the small town of Hollister and their more straight-laced fellow riders by drinking to excess and brawling. At least, that's how out-of-town media outlets portrayed the weekend. Aided by sensational coverage in the national media and The Wild One—Hollywood's gussied-up retelling of the incident—the "Hollister riot" introduced Americans to a new type of biker.

It turned out to be a prelude to a full-on P.R. nightmare. In 1950, several members of the Pissed Off Bastards broke away to form a new group, which they named for the planes some of them had flown in the war. They called themselves Hells Angels.

After Hollister, the American Motorcyclist Association declared rowdy bikers personae non gratae and barred them from joining AMA chapters. The national press had dragged the organization into new and unfamiliar territory. Founded in 1924—a descendant of the Federation of American Motorcyclists, which folded during World War I—the AMA's slogan at launch was "An organized minority can always defeat an unorganized majority." The group spent most of its time organizing competitions and helping riders start local AMA clubs, similar to chapters. It also advocated for motorcyclists' rights on the road. It was not prepared to take responsibility for supposedly traumatizing a small American town.

The troublemakers responded to their exclusion from the AMA by acting like an even smaller organized minority. They developed patches that mimicked those worn by AMA members, used military-style hierarchies to govern themselves, and set up clubs of their own. They took to calling themselves "one-percenters" and "outlaws," labels apocryphally coined by the AMA itself in a statement after Hollister.

Newspapers still wrote light stories about speed records, but by the late 1960s, they were obsessed with the Hells Angels, Pagans, Warlocks, and Banditos. The Angels became arguably the most famous gang in America in 1965 when California Attorney General Thomas C. Lynch released a six-month study focused on the group's activities in the state.

A new kind of headline began to appear in the same papers that had once celebrated the motorcycle: "Eight Are Arrested in the Torture of East Village Youth, 20, for Two Days"; "Hint of Summer Stirs Fears in Hells Angels' Neighbors"; "California Takes Steps to Curb Terrorism of Ruffian Cyclists"; "New Hampshire Town Cleans Up After Quelling Cyclists Riot."

Lawmakers and prosecutors went after the outlaw gangs, but that still left mainstream motorcyclists with the task of preserving their own reputation. The motorcycle industry and mainstream riders organized by the AMA collaborated to make a case for motorcycling as a wholesome American hobby, suitable for the whole family.

A magazine called Bike and Rider launched in 1971 with the motto "Motorcycle's New Image." An issue from August of that year features an ad discouraging bikers from cutting down their mufflers, a common practice that ratcheted up the decibel level of a motorcycle engine. "You see before you, death," the ad copy reads. "You see, this rider kills. His instrument is noise, his weapon—a bike with muffler sawed away." The ad, paid for by the Motorcycle Industry Council, concludes with the words "Noise kills."

The very next page features an ad for the publication itself featuring a white man in a light-colored suit sitting side-saddle on a parked Honda. The copy reads, "The image portrayed by the new motorcycle enthusiast is no longer that of the outlaw, but that of the people: the dentist, the electrician, even the housewife."

The motorcycle industry did its part as well. A Honda ad in a March 1973 issue of Sports Illustrated depicts a woman in corduroy pants atop a small-engine ST-90—the attitudinal antithesis of a big-engine Harley hog. She appears to be getting a riding lesson from her husband while her teenage children watch from the side. The ad copy: "At Honda, we want everyone to discover just how much fun motorcycling can be. Mom. Pop. Even the grandparents." The family is standing in front of a suburban house with a green yard and a garage.

Speaking of Harley-Davidson: The company's mass-market print ads from this era are not exactly family-friendly, but they're not scandalous either. Spots featuring trim white men in stylish clothes, always wearing helmets when depicted in motion, conjure up Steve McQueen rather than Angels leader Sonny Barger or, well, a dentist. Harley sold craftsmanship, performance, and status to squares and the middle class. Bikers sold Harleys to each other in publications like Easyrider, the pioneering magazine by and for the bad boy set, which promised to publish "Entertainment for Adult Bikers."

The AMA was helped on the P.R. front by its membership rolls. Issues of American Motorcyclist from the early 1970s featured a recurring column by Lois Gutzwiller called "Motor Maids," featuring profiles of mild-mannered female AMA members. While the association began admitting people of color in the mid-1950s, the profile subjects are mostly middle-class white women with names like Norma and Mary Ann and Gerdi and Sue. The AMA's entire October 1971 issue is dedicated to wholesome women riders. Mayra, a New Jersey librarian and grandmother, started riding after an introduction from her daughter; Jeanette, meanwhile, prefers being a passenger on her husband's bike.

The public relations effort by motorcycling's most upstanding citizens worked, at least a little bit. In between horrifying tales of biker gangs, The New York Times in 1971 found space for a story about the rise of white-collar motorcycle commuters. "The 'cycle' has grown in popularity in recent years for recreation and pleasure trips among some middle-class nonrebels," the paper noted. "Motorcycle couriers delivering messages have been joined on the road by accountants, lawyers, stockbrokers, filmmakers, computer analysts, and letter carriers."

Perhaps motorcycling would survive the Hells Angels. But winning the P.R. war wouldn't matter if bikers couldn't figure out how to win at politics as well. And by the end of the Summer of Love, it was clear to motorcycle groups that they were losing with legislators even if they were holding their own in the marketplace.

As the 1960s drew to a close, motorcycling groups and their members watched in frustration as the federal government made a small portion of highway funding contingent on states' passing mandatory helmet and seat belt legislation. Pennsylvania's 1968 helmet law was what drew Charles Umbenhauer to the statehouse in '76. At the time, he didn't like wearing a helmet and thought the choice should be left to individuals. In 1980, he joined ABATE—A Brotherhood Against Totalitarian Enactments, started by Easyriders magazine—to push for legislative changes. That's when he saw how tough grassroots politics could be.

"We had to convince our members that ABATE needed to hire a lobbyist," Umbenhauer says. "Then our first lobbyist told us we needed a political action committee. The bikers wanted to know why we needed a PAC, and the lobbyist said, 'There's only two things you can do for a legislator. You can vote for them, and you can give them money.' The bikers were furious."

Biker rage at the pay-for-play nature of politics makes sense. These men and women, many of whom had served in Vietnam, just wanted to choose whether or not to wear helmets. Hadn't they and their loved ones paid enough for that right?

As it turns out, hiring a lobbyist and starting a PAC couldn't get Pennsylvania motorcyclists what they wanted overnight. The state's ABATE chapter reorganized in 1983 as the more mild-mannered Alliance of Bikers Aimed Toward Education, but it didn't succeed at reforming Pennsylvania's mandatory helmet law until 2003. Getting it done required Congress to drop the highway funding threat, and it required bikers to synthesize the P.R. efforts of the late '60s and early '70s with a keen understanding of state politics.

ABATE did more to improve its image than change the group's name. In 1980, members began organizing an annual toy run for patients at the Children's Hospital of Pennsylvania. Motorcycle clubs around the country had been doing that kind of community volunteer work for decades, and bikers in the Keystone State knew it would draw media attention and build goodwill with their neighbors. The volunteerism paid off in a more concrete way when Umbenhauer, who became ABATE's lobbyist in 2000, ran into Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell at a toy run soon thereafter.

"Rendell said that if he ever became governor, he'd sign a helmet reform bill for us," Umbenhauer says. "He knew who ABATE was and that we were organized and doing good things." But first, Rendell needed bikers to vote for him in the statewide primary. Umbenhauer says he changed his registration from Republican to Democrat and encouraged his comrades to do the same.

"A lot of our people did that," he says. "Ed won the primary and became the governor. The first two things he said he wanted to do after he was sworn in were bring gambling to Pennsylvania and change the helmet laws for bikers. And he did both of those things."

Pennsylvania still has a helmet law, but it applies only to riders under 21. People over that age can forgo a helmet after they've been licensed for two years, or forgo it immediately by taking a state-approved motorcycle safety course. All riders of every age and experience level must wear eye protection, a concession that makes bikers less of a liability to other people on the road. Umbenhauer and ABATE call the new law "helmet choice," which Umbenhauer sold with a nifty elevator pitch: "The only snappy one-liner I ever had was, 'Hey man, we live in Pennsylvania, the cradle of liberty. Let those who ride decide.'"

Diehards like Umbenhauer are still lobbying to protect biker rights, but their constituency is dwindling. His son rides occasionally; his grandson has no interest. The lack of appeal is a little disheartening for a man who loves motorcycles so much that he asked his daughter to schedule her wedding around ABATE's legislative calendar. Umbenhauer blames the internet and handheld devices, which provide young people with a different kind of thrill.

The reality is that the American motorcycle industry and the biker scene that supports it are both in a transition phase. Harley-Davidson, perhaps the most iconic motorcycle brand in the world, is relying on nostalgic boomers with deep pockets to keep it profitable while it tries to develop and market a bike that young Americans will buy and ride. And while outlaw biker gangs are still a thing here in the United States, Umbenhauer says, "they don't have the biker wars anymore, burning down each other's clubhouses and killing each other." Umbenhauer is glad that those conflicts are (mostly) over. But he seems wistful that young Americans don't see riding a motorcycle the way he did when he was their age.

In 1971, Easyriders columnist Don Pfeil wrote that "a chopper is just about the ultimate in 'look at me—I'm different and I'm proud of it.'" Perhaps no symbol can claim that title in the internet age, when there are almost as many ways to be "different and proud of it" as there are people who want to say that about themselves.

American domestic motorcycle sales now make up roughly 2 percent of the global total, and the most popular bikes outside the U.S. are actually more akin to scooters. Small engines and light frames make them more nimble and thus better suited than American hogs for navigating congested streets in the densely populated cities of Europe and the developing world.

It might also be the case that bikers are victims of their own success. They worked hard for decades to raise the social standing of motorcyclists, and now any and every kind of person can commute to work on a motorcycle or cruise on the weekends. Young people might see boomer enthusiasm as a turnoff—the biker lifestyle can read as dated, like steakhouses and big Cadillacs. Maybe, to love a chromed hog and ape-hanger handlebars and the sound of a V-Twin hitting its sweet spot, you had to be alive and young when riding that kind of motorcycle was synonymous with opting out of polite society or bucking the generation that preceded you. Young people today have safer ways to opt out; meanwhile, their parents have matching helmets.

Umbenhauer made peace with that possibility earlier this year when he rode his Harley to a movie theater near Harrisburg to catch a 50th anniversary rerelease of Easy Rider. The 1969 film spoke to and for bikers in a way that no film has before or since. Peter Fonda's character is neither a thug nor a square playing weekend warrior. He is instead the biker archetype—outside the system but also above it, neither itching for a fight nor scared of one. Umbenhauer was 24 when he first saw the movie. He worried the rerelease would sell out.

"I got there early," he says. But he could've taken his time. There were no motorcycles in the parking lot and only about 20 people in the theater. "Everybody was either in a wheelchair or walking with a cane."